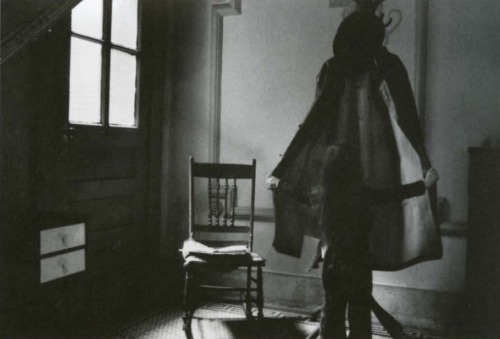

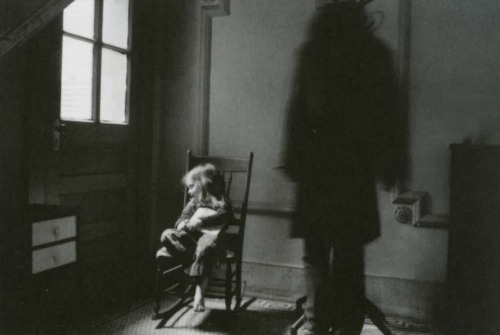

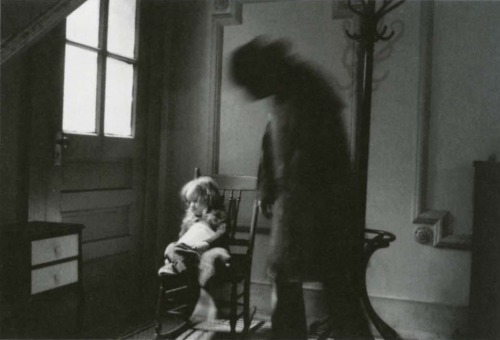

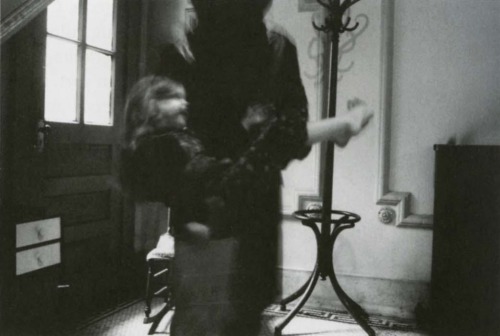

I Once Dated A Writer And

I Once Dated A Writer and

Writers are forgetful, but they remember everything. They forget appointments and anniversaries, but remember what you wore, how you smelled, on your first date… They remember every story you’ve ever told them - like ever, but forget what you’ve just said. They don’t remember to water the plants or take out the trash, but they don’t forget how to make you laugh. . Writers are forgetful because they’re busy remembering the important things.

More Posts from Ainesseyspiegel and Others

Writing Sex

Okay, so I saw a post recently on writing sex, and it got me thinking about some things. What is the best way to incorporate sex scenes into fiction?

I think it really depends on the mood and tone of the story/poem/novel. Unless you are writing specifically children or teen lit, I think anything sexual is fair game, although the words you use and the amount of detail you go into will shape the tone of your story. A lot of the time, the build-up to sex is much more important to focus on than the actual sex in writing fiction. Focusing on emotions between the two characters, physical sensations they encounter at the thought of sex, and the way the two people fall into bed together will help keep your otherwise serious mystery novel with a side of romance from turning into porn. Describing sex acts in detail and using specific words for genitalia, in my opinion, cheapens the work and can make it tawdry rather than titillating.

Of course, you’re not always trying to say the same thing, and a lot of how sex scenes function is determined by the plot and characters. I find that when my characters are having a sexual encounter that is awkward, uncomfortable, frightening, traumatic, dangerous, etc., I will go into more specific detail about the actual sex acts, whereas in writing a scene between two people in love, I will be much more vague and focus more on emotions and what the scene means to them. Another instance where describing the sex more specifically can be necessary is if it’s a character’s first time; going through how the character is taking it all in, what he/she doesn’t know about what he/she is doing, what feels new, good, wrong, etc. can be helpful in moving the story along, if it is a virginal scene.

Most importantly, I think it’s just good to remember to use sex scenes the way you would any other scene: if it’s essential to furthering the plot or the development of the characters, go for it. If it’s not, leave it out.

What do you other writerly folks think? How/when/why do you write sex scenes?

ʜᴏᴡ ᴛᴏ: ғᴏʀᴍᴀʟʟʏ ᴀᴅᴅʀᴇss ʀᴏʏᴀʟᴛʏ/ᴀʀɪsᴛᴏᴄʀᴀᴄʏ ɪɴ ᴘᴇʀsᴏɴ

This is more for my own reference, but if anyone else finds this useful, you’re free to like/reblog it and what-not. Most of the information was either taken from various Wikipedia pages or WikiHow.

First, let’s look at the social hierarchy:

Emperor/Empress

King/Queen

Grand Duke/Grand Duchess

Grand Prince/Grand Princess

Archduke/Archduchess

Duke/Duchess

Prince/Princess

Marquis/Marchioness

Count (Earl)/Countess

Viscount/Viscountess

Baron/Baroness

Knight/Dame

Sir/Lady

When meeting royalty for the first time, always acknowledge them with a bow from the neck (not the waist) if you are a man, and a small curtsey if you are a woman. (This gesture is no longer applicable in today’s world, but if you’re writing for an earlier time period, then it’s important your character bow or curtsey).

Below is directly applicable to citizens of the U.K and Commonwealth:

Only shake the queen’s hand if she offers it to you first. If you are wearing gloves, do not remove them.

Do not begin a conversation with the queen. Instead, wait until she starts speaking to you.

When addressing royalty, finish your first reply with their formal address. For example, if a prince asks you, “How are you enjoying the United Kingdom?” you would respond “It’s wonderful, Your Royal Highness.” Each title carries a different formal address:

Emperors and Empresses are addressed as “Your Imperial Majesty” and introduced as “His/Her Imperial Majesty”.

Queens and kings are addressed as “Your Majesty.” Introduce them as “Her Majesty the Queen” (not ”Queen of England”, as she is the “Queen of the United Kingdom”, “Queen of Canada” and a long array of additional titles).

Princes and princesses are referred to “Your Royal Highness.” Introduce them as “His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.” Any child or male line grandchild of a monarch is considered a prince or princess. The spouse of a prince is also a princess, although she is not always “Princess” Her First Name. The spouse of a princess is not always a prince. Great-grandchildren in the male line of the monarch are not considered princes or princesses. Use the courtesy titles lord or lady for these personages, addressing them as, for example, “Lady Jane” and introducing them as “Lady Jane Windsor” (unless they have a different title of their own).

Dukes and Duchesses are called “Your Grace” or “Duke/Duchess.” Introduce the duke to someone else as “His Grace the Duke of Norfolk,” the duchess as “Her Grace the Duchess of Norfolk”.

Baronets and knights, if male, are addressed as “Sir Bryan” (if his name is Bryan Thwaites) and his wife is “Lady Thwaites”. You would introduce him using his full name, “Sir Bryan Thwaites,” and his wife as “Lady Thwaites.”

Dames (the equivalent of knighthood for women - there is no female equivalent of baronetcy) are “Dame Gertrude” in conversation, and you would introduce her as “Dame Gertrude Mellon.”

Other forms of nobility (including Marquess/Marchioness, Earl/Countess, Viscount/Viscountess, Baron/Baroness) are generally addressed as, “Lord or Lady Trowbridge” (for the Earl of Trowbridge), and introduced with their appropriate title, such as “Viscount Sweet” or “Baroness Rivendell” .

Use “Sir” or “Ma’am” thereafter. If the noble uses a casual style of conversation, drop the “Sir” or “Ma’am.” Don’t make them have to ask.

This information strictly deals with meeting British peers and royalty.Other parts of the world have different systems of aristocracy, and while the British royal family’s official website notes that when meeting a member of the royal family, “There are no obligatory codes of behaviour - simply courtesy,” this is not the case for all aristocracies. Failure to observe specific codes of behaviour in some countries may result in harsh punishment.

So—— it’s always best to research the monarchy in which you are writing for. I used the U.K’s peerage system because it’s the most widely known, but don’t take it as applicable for every monarchy. Titles and protocols can differ greatly between cultures.

If any of this information is incorrect, please feel free to correct it.

Shop , Patreon , Books and Cards , Mailing List

“There is no real ending. It’s just the place where you stop the story.”

— Frank Herbert (via writingdotcoffee)

-

aquameme reblogged this · 1 month ago

aquameme reblogged this · 1 month ago -

colourful-drugs liked this · 1 month ago

colourful-drugs liked this · 1 month ago -

ainesseyspiegel reblogged this · 2 months ago

ainesseyspiegel reblogged this · 2 months ago -

daengeli liked this · 2 months ago

daengeli liked this · 2 months ago -

savemetonightt reblogged this · 3 months ago

savemetonightt reblogged this · 3 months ago -

lokirarenee liked this · 7 months ago

lokirarenee liked this · 7 months ago -

annak97t6 liked this · 7 months ago

annak97t6 liked this · 7 months ago -

annita890dzmzfmh liked this · 7 months ago

annita890dzmzfmh liked this · 7 months ago -

shadowandecho reblogged this · 7 months ago

shadowandecho reblogged this · 7 months ago -

nanacee reblogged this · 7 months ago

nanacee reblogged this · 7 months ago -

deactivated-posts reblogged this · 9 months ago

deactivated-posts reblogged this · 9 months ago -

virologramland804 liked this · 11 months ago

virologramland804 liked this · 11 months ago -

ekwanderer liked this · 1 year ago

ekwanderer liked this · 1 year ago -

bonesprout liked this · 1 year ago

bonesprout liked this · 1 year ago -

pagetreader-archived liked this · 1 year ago

pagetreader-archived liked this · 1 year ago -

meerawrites liked this · 1 year ago

meerawrites liked this · 1 year ago -

musicboxmemories reblogged this · 1 year ago

musicboxmemories reblogged this · 1 year ago -

deactivated-posts reblogged this · 1 year ago

deactivated-posts reblogged this · 1 year ago -

queenofcrazy27 liked this · 1 year ago

queenofcrazy27 liked this · 1 year ago -

fightlikeabutterfly liked this · 1 year ago

fightlikeabutterfly liked this · 1 year ago -

musicboxmemories liked this · 1 year ago

musicboxmemories liked this · 1 year ago -

thatgirlmj reblogged this · 1 year ago

thatgirlmj reblogged this · 1 year ago -

thatgirlmj liked this · 1 year ago

thatgirlmj liked this · 1 year ago -

abilouwrites liked this · 1 year ago

abilouwrites liked this · 1 year ago -

midnightsnyx reblogged this · 1 year ago

midnightsnyx reblogged this · 1 year ago -

readbookswithpepi reblogged this · 1 year ago

readbookswithpepi reblogged this · 1 year ago -

readbookswithpepi liked this · 1 year ago

readbookswithpepi liked this · 1 year ago -

betterthanakickintheface reblogged this · 1 year ago

betterthanakickintheface reblogged this · 1 year ago -

betterthanakickintheface liked this · 1 year ago

betterthanakickintheface liked this · 1 year ago -

middlefade liked this · 1 year ago

middlefade liked this · 1 year ago -

tobiaslovesmydauntlesscake liked this · 1 year ago

tobiaslovesmydauntlesscake liked this · 1 year ago -

laharvalla reblogged this · 1 year ago

laharvalla reblogged this · 1 year ago -

momoppi liked this · 1 year ago

momoppi liked this · 1 year ago -

illuminated-fox liked this · 1 year ago

illuminated-fox liked this · 1 year ago -

crunchyspositivybubble liked this · 1 year ago

crunchyspositivybubble liked this · 1 year ago -

anchoringlove liked this · 1 year ago

anchoringlove liked this · 1 year ago -

ymdslf reblogged this · 1 year ago

ymdslf reblogged this · 1 year ago -

gqutie-blog liked this · 1 year ago

gqutie-blog liked this · 1 year ago -

wellfedfears reblogged this · 1 year ago

wellfedfears reblogged this · 1 year ago -

peacewithinme reblogged this · 1 year ago

peacewithinme reblogged this · 1 year ago -

jaszirae liked this · 1 year ago

jaszirae liked this · 1 year ago -

flawedhoneyy reblogged this · 1 year ago

flawedhoneyy reblogged this · 1 year ago -

sexynakedblackguy reblogged this · 1 year ago

sexynakedblackguy reblogged this · 1 year ago -

blobsandberries liked this · 1 year ago

blobsandberries liked this · 1 year ago