51 posts

Latest Posts by amateurchemstudent - Page 2

If you are scrolling through Tumblr trying to distract yourself from something you don’t want to think about, or you’re looking for a sign. It is going to be okay. Just breathe. You are alive and you matter.

Universities are like "we can't accept everyone based on accepted grades because we gave too many offers out." They give out too many offers because they're horrified at the thought that they might end up with too many empty places on courses, so they oversubscribe so they can get those sweet sweet tuition fees.

Just in case anyone thought here was a thing that Tony Blair had no hand in, for once.

The UK’s academic pipeline is failing to retain Black, Asian and other ethnic minority chemists, an analysis by the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Inclusion and Diversity team has shown. The figures are particularly stark for Black students, who are far less likely than white students to be pursuing a PhD and higher academic positions.

While the numbers of UK domiciled ethnic minority students entering chemistry degrees mirror the general population, the figures change dramatically as these students advance through academia’s career stages. At undergraduate, Asian students are around 14% of the population, dropping to 7% at postgraduate. For Black students, the drop is even more severe, from about 5% at undergraduate to just over 1% at postgraduate.

‘Beyond the PhD, the numbers absolutely diminish to the very senior levels of academia, where it is essentially barren ground for Black chemists,’ comments Robert Mokaya, who works on sustainable energy materials at the University of Nottingham. ‘When I was promoted in 2008, I was very aware that there was a lack of others like me but was unaware that I was possibly the first Black chemistry professor in the UK,’ says Mokaya. ‘My hope then was that there would be others. But I don’t know of any other appointment since then. And of course that is really very disappointing.’

Continue Reading.

Today is #InternationalMakeUpDay! Here’s a graphic looking at the various components of nail polish 💅 https://ift.tt/32fnwAh https://ift.tt/3jWclTk

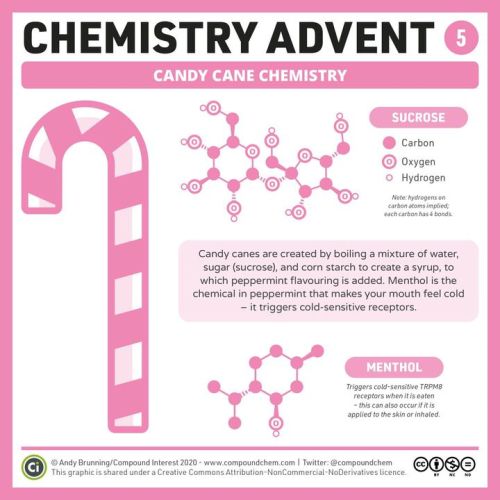

It’s day 5 of #ChemAdvent – here’s why peppermint candy canes make your mouth feel cold! bit.ly/chemadvent2020 https://ift.tt/2JM6bZ7

Water: Making a Splash

You don’t have to be a genius to know that water is essential for life. After all, we’re made up of it, we sweat it, we drink it, some people even opt to give birth in it. But what is it about two hydrogens and an oxygen which make it so sensational?

The answer is to do with water’s structure. A H2O molecule is covalently bonded, which means each atom shares electrons. In this case, the covalent bonds are between two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Oxygen is cool because it is highly electronegative. Electronegativity is the ability for one atom to “pull” the electrons towards it in a covalent bond. Since oxygen is highly electronegative, it pulls the electrons in the bond towards it which gives the oxygen a slight negative charge because of the electron proximity. This is represented by δ- (delta negative). The hydrogen is therefore δ+ (delta positive) and has a slight positive charge. Overall, the molecule is said to be polar, or to be dipolar in nature, because there is a difference in charge across the molecule.

Water being a dipole gives it different properties, which you need to know about if you are sitting the AS or A level biology exam.

A quick note on hydrogen bonding…

Being a dipole, water has areas of different charge. When many molecules come together, hydrogen bonds can form between H+ on one molecule and O- on another, shown in the diagram with a dashed line.

It is hydrogen bonds which give water a property called surface tension. Water has a high tendency to ‘stick together’, called cohesion. This is important in water transport through the xylem in later units. Surface tension is a bit like a “skin” because it can allow small organisms to walk along it. It occurs because water molecules on the surface bond to their neighbours much like throughout the whole liquid, but since one side is exposed to air and cannot form hydrogen bonds upwards, they will form stronger ones with the molecules beside them. The net attraction is downwards.

Water is good as a temperature buffer too. Heating a substance makes its particles gain more kinetic energy and therefore the overall temperature rises since particles are moving faster. With water, the temperature doesn’t rise as much as other liquids do. This is because it takes more heat energy to raise the temperature of water by 1 degree - it has a high specific heat capacity due to the many hydrogen bonds that have to be broken (even though they are weak on their own). It takes a lot of heat energy for water to raise its temperature significantly.

This is useful in organisms because our cells are mostly water, which can absorb heat energy without raising our temperature very much. Therefore it “buffers” or reduces heat changes. Seas, lakes and oceans are all good environments to live in because they do not change temperature as quickly as air. Aquatic organisms have an environment with less temperature fluctuation than land organisms.

Having a high latent heat of vaporisation means water can cool down organisms by evaporating a small amount of water. Evaporation is when water becomes a gas due to the large amount of KE. Fast-moving molecules are removed when this occurs and take their energy with them, therefore decreasing the amount of energy left behind and cooling it. Sweat is a good example of high latent heat of vaporisation. A small quantity of water is removed with a large cooling effect, meaning temperature is stabilised without losing a lot of water.

Water is also a good solvent (a substance which can dissolve other substances) and this is due to more hydrogen bonding. Water’s charges of H+ and O- are attracted to the positive and negative charges on molecules and therefore solutes such as NaCl are split into Na+ and Cl-, then spread out. Solvent properties are important in transport (such as blood plasma dissolving glucose, vitamins, urea etc), metabolic reactions, urine production and mineral transportation through the xylem and phloem in plants.

Water molecules can also take place in metabolic reactions. Hydrolysis reactions involve breaking down the covalent bonds between hydrogen and oxygen and making new ones, for example, in digestion. Condensation reactions produce water as a byproduct e.g. the formation of phosphodiester bonds. Water is referred to as a metabolite.

Summary

Water is a dipole due to the slight opposite charges on oxygen and hydrogen atoms.

Hydrogen bonds form between hydrogens on one water molecule and oxygens on another.

Because of this, water has the tendency to stick to itself - cohesion. Cohesion is the reason for surface tension.

Water is a good temperature buffer because of its high specific heat capacity. It takes a lot of energy to raise the temperature by a degree.

Water has a high latent heat of vaporisation so evaporating a little has a large cooling effect.

Water is a good solvent because of how the hydrogen bonds attract charged molecules and separate them. This is useful for transporting solutions.

Water is a metabolite important for hydrolysis reactions and produced in condensation reactions.

Happy studying!

Enthalpy - a thermodynamic property

When I first learned about enthalpy, I was shocked - it felt more like a physics lesson than a chemistry lesson. The thought of learning more about thermodynamics than my basic understanding from my many science lessons in lower school made me bored out of my mind. But enthalpy is actually pretty interesting, once you get your head around it…

Reactions which release heat to their surroundings are described to be exothermic. These are reactions like combustion reactions, oxidation reactions and neutralisation reactions. Endothermic reactions take in heat from their surroundings, such as in thermal decomposition. Reversible reactions are endothermic in one direction and exothermic in the other.

These facts are important when you start to look at enthalpy. Enthalpy is basically a thermodynamic property linked to internal energy, represented by a capital H. This is pretty much the energy released in bond breaking and made in bond making. We usually measure a change in enthalpy, represented by ∆H. ∆H = enthalpy of the products (H1) - enthalpy of the reactants (H2). This is because we cannot measure enthalpy directly.

In exothermic reactions, ∆H is negative whereas in endothermic reactions, ∆H is positive.

∆H is always measured under standard conditions of 298K and 100kPa.

In reversible reactions, the ∆H value is the same numerical value forwards and backwards but the sign is reversed. For example, in a forward exothermic reaction, the ∆H value would be -ve but in the backwards reaction (endothermic) the ∆H would be +ve.

Reaction profiles are diagrams of enthalpy levels of reactants and products in a chemical reaction. X axis is enthalpy rather than ∆H and the Y axis is the progress of reaction, reaction coordinate or extent of reaction. Two horizontal lines show the enthalpy of reactants and products with the reactants on the left and the products on the right. These should be labelled with their names or formulae.

In an endothermic reaction, product lines are higher enthalpy values than reactants. In an exothermic reaction, product lines are lower enthalpy values than reactants. The difference between product and reactant lines is labelled as ∆H. Values are measured in kJ mol-1.

Reaction pathways are shown with lines from the reactants to the products on enthalpy level diagrams. This shows the “journey” that the enthalpy takes during a reaction. They require an input of energy to break bonds before new bonds can form the products. The activation energy is the peak of the pathway above the enthalpy of reactants. It is the minimum amount of energy that reactants must have to react.

Standard enthalpy values are the ∆H values for enthalpy changes of specific reactions measured under standard conditions, represented by ⊖. There are three of these:

1. Standard enthalpy of reaction ( ΔHr⊖ )

The enthalpy change when substances react under standard conditions in quantities given by the equation for the reaction.

2. Standard enthalpy of formation ( ΔfH⊖ )

The enthalpy change when 1 mole of a compound is formed from its constitutent elements with all reactants and products in standard states under standard conditions.

The enthalpy of formation for an element is zero is it is in it’s standard state for example, O2 enthalpy is zero.

3. Standard enthalpy of combustion ( ΔcH⊖ )

The enthalpy change when 1 mole of a substance is burned completely in excess oxygen with all reactants and products in their standard states under standard conditions.

Values for standard enthalpy of formation and combustion must be kept to per mole of what they refer.

Summary

Reactions which release heat to their surroundings are described to be exothermic. Endothermic reactions take in heat from their surroundings, such as in thermal decomposition.

Reversible reactions are endothermic in one direction and exothermic in the other.

Enthalpy is a thermodynamic property linked to internal energy, represented by a capital H. We usually measure a change in enthalpy, represented by ∆H.

∆H = enthalpy of the products (H1) - enthalpy of the reactants (H2). We cannot measure enthalpy directly.

In exothermic reactions, ∆H is negative whereas in endothermic reactions, ∆H is positive.

∆H is always measured under standard conditions of 298K and 100kPa.

In reversible reactions, the ∆H value is the same numerical value forwards and backwards but the sign is reversed.

Reaction profiles are diagrams of enthalpy levels of reactants and products in a chemical reaction. They

In an endothermic reaction, product lines are higher enthalpy values than reactants. In an exothermic reaction, product lines are lower enthalpy values than reactants.

The difference between product and reactant lines is labelled as ∆H.

Values are measured in kJ mol-1.

Reaction pathways are shown with lines from the reactants to the products on enthalpy level diagrams. They plot enthalpy against reaction progress.

Reactions require an input of energy to break bonds before new bonds can form the products. The activation energy is the peak of the pathway above the enthalpy of reactants. It is the minimum amount of energy that reactants must have to react.

Standard enthalpy values are the ∆H values for enthalpy changes of specific reactions measured under standard conditions, represented by ⊖.

Standard enthalpy of reaction ( ΔHr⊖ ) is the enthalpy change when substances react under standard conditions in quantities given by the equation for the reaction.

Standard enthalpy of formation ( ΔfH⊖ ) is the enthalpy change when 1 mole of a compound is formed from its constitutent elements with all reactants and products in standard states under standard conditions.

The enthalpy of formation for an element is zero is it is in it’s standard state.

Standard enthalpy of combustion ( ΔcH⊖ ) is the enthalpy change when 1 mole of a substance is burned completely in excess oxygen with all reactants and products in their standard states under standard conditions.

Values for standard enthalpy of formation and combustion must be kept to per mole of what they refer.

Happy studying!

Covalent and Dative Bonds

Covalent and dative (sometimes called co-ordinate) bonds occur between two or more non-metals, e.g. carbon dioxide, water, methane and even diamond. But what actually are they?

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. They are found in molecular elements or compounds such as chlorine or sulfur, but also in macromolecular elements and compounds like SiO2 and graphite. Covalent bonds are also found in molecular ions such as NH4+ and HCO3-.

Single covalent bonds have just one shared pair of electrons. Regularly, each atom provides one unpaired electron (the amount of unpaired electrons is usually equal to the number of covalent bonds which can be made) in the bond. Double covalent bonds have two shared pairs of electrons, represented by a double line between atoms, for example, O=C=O (CO2). Triple covalent bonds can also occur such as those in N ≡ N.

Dot and cross diagrams represent the arrangement of electrons in covalently bonded molecules. A shared pair of electrons is represented by a dot and a cross to show that the electrons come from different atoms.

Unpaired electrons are used to form covalent bonds as previously mentioned. The unpaired electrons in orbitals of one atom can be shared with another unpaired electron in an orbital but sometimes atoms can promote electrons into unoccupied orbitals in the same energy level to form more bonds. This does not always occur, however, meaning different compounds can be formed - PCl3 and PCl4 are examples of this.

An example where promotion is used is in sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). The regular configuration of sulfur atoms is 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p4. It promotes, as shown in the diagram (see excited state), two electrons: one from the 3s electrons to the 3d orbital and one from the 3p to the 3d. Therefore there are 6 unpaired electrons for fluorine atoms to join. It has an octahedral structure.

An atom which has a lone pair (a pair of electrons uninvolved in bonding) of electrons can form a coordinate bond with the empty orbital of another atom. It essentially donates an electron into this orbital which when formed, acts the same as a normal covalent bond. A coordinate bond therefore contains a shared pair of electrons that have come from one atom.

When ammonia reacts with a H+ ion, a coordinate bond is formed between the lone pair on the ammonia molecule and the empty 1s sub-shell in the H+ ion. An arrow represents the dative covalent bond (coordinate bond). Charges on the final ion must be showed.

Summary

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. They are found in molecular elements or compounds as well as in macromolecular elements and compounds. Also found in molecular ions.

Single covalent bonds have just one shared pair of electrons. Double covalent bonds have two shared pairs of electrons, represented by a double line between atoms. Triple covalent bonds can also occur.

Dot and cross diagrams represent the arrangement of electrons in covalently bonded molecules. A shared pair of electrons is represented by a dot and a cross to show that the electrons come from different atoms.

Unpaired electrons are used to form covalent bonds - they can be shared with another unpaired electron in an orbital but sometimes atoms can promote electrons into unoccupied orbitals in the same energy level to form more bonds. This does not always occur, however, meaning different compounds can be formed.

An example where promotion is used is in sulfur hexafluoride (SF6).

An atom which has a lone pair (a pair of electrons uninvolved in bonding) of electrons can form a coordinate bond with the empty orbital of another atom.

It donates an electron into this orbital which when formed, acts the same as a normal covalent bond. A coordinate bond therefore contains a shared pair of electrons that have come from one atom.

When ammonia reacts with a H+ ion, a coordinate bond is formed between the lone pair on the ammonia molecule and the empty 1s sub-shell in the H+ ion. An arrow represents the dative covalent bond (coordinate bond). Charges on the final ion must be showed.

Structural Isomerism

In one boring history lesson, you and your friend (who both love chemistry) are doodling displayed formulas in the back of your textbook. You both decide to draw C5H12 - however, when you come to name what you’ve drawn, your friend has something completely different. You know what you’ve drawn is pentane and your friend knows what they’ve drawn is 2,3-dimethylpropane. So which one is C5H12?

The answer is both! What you and your friend have hypothetically drawn are structural isomers of C5H12 (another is 2-methylbutane). These are compounds which have the same molecular formula but different structural formulas.

Isomers are two or more compounds with the same formula but a different arrangement of atoms in the molecule and often different properties.

There are several different kinds of structural isomers: chain, positional and functional group.

Chain isomerism happens when there is more than one way of arranging carbon atoms in the longest chain. If we continue with the example C5H12, it exists as the three chain isomers shown above. Chain isomers have similar chemical properties but different physical properties because more branched isomers have weaker Van der Waals and therefore lower boiling points.

Positional isomers have the same carbon chain and the same functional group but it is attached at different points along the chain.

This is a halogenoalkane. The locant “1″ describes where the chlorine is on the chain. For more on naming organic compounds, check out my nomenclature post.

The final type of isomer you need to know is a functional group isomer. This is a compound with the same molecular formula but a different functional group. For example, C2H6O could be ethanol or methoxymethane.

And surprisingly, that is all you need to know for the AS exam. There are also things called stereoisomers but those will be covered next year. Just make sure you know how to name and draw the three different kinds of structural isomers for the exam. Practice makes perfect!

SUMMARY

Structural isomers are compounds which have the same molecular formula but different structural formulas.

Isomers are two or more compounds with the same formula but a different arrangement of atoms in the molecule and often different properties.

There are several different kinds of structural isomers: chain, positional and functional group.

Chain isomerism happens when there is more than one way of arranging carbon atoms in the longest chain. Chain isomers have similar chemical properties but different physical properties because more branched isomers have weaker Van der Waals and therefore lower boiling points.

Positional isomers have the same carbon chain and the same functional group but it is attached at different points along the chain.

A functional group isomer is a compound with the same molecular formula but a different functional group.

Happy studying!

Combusting Alkanes

If you follow this blog, by now you must be thinking, when will we be done with the alkane chemistry? Well, the answer is never. There is still one more topic to touch on - burning alkanes and the environmental effects. Study up chums!

Alkanes are used as fuels due to how they can combust easily to release large amounts of heat energy. Combustion is essentially burning something in the presence of oxygen. There are two types of combustion: complete and incomplete.

Complete combustion occurs when there is a plentiful supply of air. When an alkane is burned in sufficient oxygen, it produces carbon dioxide and water. How much depends on what is being burnt. For example:

butane + oxygen -> carbon dioxide + water

2C4H10 (g) + 13O2 (g) -> 8CO2 (g) + 10H2O (g)

Remember state symbols in combustion reactions. In addition, this reaction can be halved to balance for 1 mole of butane by using fractions when dealing with the numbers.

C4H10 (g) + 6 ½ O2 (g) -> 4CO2 (g) + 5H2O (g)

Incomplete combustion on the other hand occurs when there is a limited supply of air. There are two kinds of incomplete combustion. The first type produces water and carbon monoxide.

butane + limited oxygen -> carbon monoxide + water

C4H10 (g) + 4 ½ O2 (g) -> 4CO (g) + 5H2O (g)

Carbon monoxide is dangerous because it is toxic and undetectable due to being smell-free and colourless. It reacts with haemoglobin in your blood to reduce their oxygen-carrying ability and can cause drowsiness, nausea, respiratory failure or death. Applicances therefore must be maintained to prevent the formation of the monoxide.

The other kind of incomplete combustion occurs in even less oxygen. It produces water and soot (carbon).

butane + very limited oxygen -> carbon + water

C4H10 (g) + 2 ½ O2 (g) -> 4C (g) + 5H2O (g)

Internal combustion engines work by changing chemical energy to kinetic energy, fuelled by the combustion of alkane fuels in oxygen. When this reaction is undergone, so do other unwanted side reactions due to the high pressure and temperature, e.g. the production of nitrogen oxides.

Nitrogen is regularly unreactive but when combined with oxygen, it produces NO and NO2 molecules:

nitrogen + oxygen -> nitrogen (II) oxide

N2 (g) + O2 (g) -> 2NO (g)

and

nitrogen + oxygen -> nitrogen (II) oxide

N2 (g) + 2O2 (g) -> 2NO2 (g)

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is sometimes present in the exhaust mixture as impurities from crude oil. It is produced when sulfur reacts with oxygen. Nitrogen oxides, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, carbon particles, unburnt hydrocarbons, water vapour and sulfur dioxide are all produced in exhaust fumes and are also pollutants that cause problems you need to be aware of for the exam as well as how to get rid of them.

Greenhouse gases contribute to global warming, an important process where infrared radiation from the sun is prevented from escaping back into space by atmospheric gases. On the one hand, some greenhouse gases need to continue this so that the earth can sustain life as it traps heat, however, we do not want the earth’s temperature to increase that much. Global warming is the term given to the increasing average temperature of the earth, which has seen an increase in the last few years due to human activity - burning fossil fuels like alkanes has produced more gases which trap more heat. Examples of greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide, methane and water vapour.

Another pollution problem the earth faces is acid rain. Rain water is already slightly acidic due to the CO2 present in the atmosphere but acid rain is more acidic than this. Nitrogen oxides contribute to acid rain although sulfur dioxide is the main cause. The equation for sulfur dioxide reacting with water in the air to produce oxidised sulfurous acid and therefore sulphuric acid is:

SO2 (g) + H2O (g) + ½ O2 (g) -> H2SO4 (aq)

Acid rain is a problem because it destroys lakes, buildings and vegetation. It is also a global problem because it can fall far from the original source of the pollution.

Photochemical smog is formed from nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and unburnt hydrocarbons that react with sunlight. It mostly forms in industralised cities and causes health problems such as emphysema.

So what can we do about the pollutants?

A good method of stopping pollution is preventing it in the first place, therefore cars have catalytic converters which reduce the amount of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and unburnt hydrocarbons come into the atmosphere by converting them into less toxic gases. Shaped like a honeycomb for increased SA and therefore rate of conversion, platinum and rhodium coat ceramic and act as catalysts for the reactions that take place in an internal combustion engine.

As they pass over the catalyst, they react with each other to form less pollution:

octane + nitrogen (II) oxide -> carbon dioxide + nitrogen + water

C8H18 (g) + 25NO -> 8CO2 (g) + 12 ½ N2 (g) + 9H2O (g)

nitrogen (II) oxide + carbon monoxide -> carbon dioxide + nitrogen

2NO (g) + 2CO (g) -> 2CO2 (g) + N2 (g)

Finally, sulfur dioxide must be dealt with. The first way it is dealt with is by removing it from petrol before it can be burnt, however, this is often not economically favourable for fuels used in power stations. A process called flue gas desulfurisation is used instead.

In this, gases are passed through a wet semi-solid called a slurry that contains calcium oxide or calcium carbonate. These neutralise the acid, due to being bases, to form calcium sulfate which has little commercial value but can be oxidised to produce a more valuable construction material.

calcium oxide + sulfur dioxide -> calcium sulfite

CaO (s) + SO2 (g) -> CaSO3 (s)

calcium carbonate + sulfur dioxide -> calcium sulfite + carbon dioxide

CaCO3 (s) + SO2 (g) -> CaSO3 (s) + CO2 (g)

calcium sulfite + oxygen -> calcium sulfate

CaSO3 (s) + O -> CaSO4 (s)

SUMMARY

Alkanes are used as fuels due to how they can combust easily to release large amounts of heat energy. Combustion is essentially burning something in the presence of oxygen.

Complete combustion occurs when there is a plentiful supply of air. When an alkane is burned in sufficient oxygen, it produces carbon dioxide and water

Remember state symbols in combustion reactions. In addition, reactions can be halved to balance for 1 mole of compounds by using fractions when dealing with the numbers.

Incomplete combustion occurs when there is a limited supply of air. There are two kinds of incomplete combustion.

The first type produces water and carbon monoxide.

Carbon monoxide is dangerous because it is toxic and undetectable due to being smell-free and colourless. It reacts with haemoglobin in your blood to reduce their oxygen-carrying ability and can cause drowsiness, nausea, respiratory failure or death.

The other kind of incomplete combustion occurs in even less oxygen. It produces water and soot (carbon).

Internal combustion engines work by changing chemical energy to kinetic energy, fuelled by the combustion of alkane fuels in oxygen. When this reaction is undergone, so do other unwanted side reactions due to the high pressure and temperature, e.g. the production of nitrogen oxides.

Nitrogen is regularly unreactive but when combined with oxygen, it produces NO and NO2 molecules:

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is sometimes present in the exhaust mixture as impurities from crude oil. It is produced when sulfur reacts with oxygen.

Nitrogen oxides, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, carbon particles, unburnt hydrocarbons, water vapour and sulfur dioxide are all produced in exhaust fumes and are also pollutants that cause problems you need to be aware of for the exam as well as how to get rid of them.

Greenhouse gases contribute to global warming, an important process where infrared radiation from the sun is prevented from escaping back into space by atmospheric gases. Some greenhouse gases need to continue this so that the earth can sustain life as it traps heat, however, we do not want the earth’s temperature to increase that much. Global warming is the term given to the increasing average temperature of the earth, which has seen an increase in the last few years due to human activity - burning fossil fuels like alkanes has produced more gases which trap more heat.

Another pollution problem the earth faces is acid rain. Nitrogen oxides contribute to acid rain although sulfur dioxide is the main cause.

Acid rain is a problem because it destroys lakes, buildings and vegetation. It is also a global problem because it can fall far from the original source of the pollution.

Photochemical smog is formed from nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and unburnt hydrocarbons that react with sunlight. It mostly forms in industralised cities and causes health problems such as emphysema.

A good method of stopping pollution is preventing it in the first place, therefore cars have catalytic converters which reduce the amount of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and unburnt hydrocarbons come into the atmosphere by converting them into less toxic gases. Shaped like a honeycomb for increased SA and therefore rate of conversion, platinum and rhodium coat ceramic and act as catalysts for the reactions that take place in an internal combustion engine.

As they pass over the catalyst, they react with each other to form less pollution.

octane + nitrogen (II) oxide -> carbon dioxide + nitrogen + water

C8H18 (g) + 25NO -> 8CO2 (g) + 12 ½ N2 (g) + 9H2O (g)

nitrogen (II) oxide + carbon monoxide -> carbon dioxide + nitrogen

2NO (g) + 2CO (g) -> 2CO2 (g) + N2 (g)

Finally, sulfur dioxide must be dealt with. The first way it is dealt with is by removing it from petrol before it can be burnt, however, this is often not economically favourable for fuels used in power stations. A process called flue gas desulfurisation is used instead.

In this, gases are passed through a wet semi-solid called a slurry that contains calcium oxide or calcium carbonate. Since they are bases, these neutralise the acid to form calcium sulfate which has little commercial value but can be oxidised to produce a more valuable construction material.

Happy studying!

Breaking Down Alkanes - isn’t it cracking?

Unfortunately, if you’re sitting your A Level chemistry exam, you need to know a little more than the basic properties of alkanes outlined in my last post. Luckily though, this post takes you through fractional distillation and the two types of cracking - isn’t that convenient?

Crude oil contains carbon compounds formed by the effects of pressure and high temperature on plant and animal remnants. It is viscious, black and found in rocks beneath the earth’s surface. It is a mixture of mainly alkane hydrocarbons which are separated by a process called fractional distillation. Crude oil is essential because it is burned as a fuel and each fraction has different properties e.g. diesel, petrol, jet fuel.

Fractional distillation is the continual evaporation and condensation of a mixture which causes fractions to split due to a difference in boiling point. It is important to note that fractional distillation does not separate crude oil into pure compounds but rather less complex mixtures. Fractions are groups of compounds that have similar boiling points and are removed at the same level of a fractionating column.

The first step in this process is to heat crude oil in a furnace until some changes state from a liquid to a vapour. This mixture goes up a fractionating tower or column which is hotter at the bottom than the top and reaches a layer which is cool enough to condense and be collected. Shorter chain molecules are collected at the top where it is cooler since they have lower boiling points.

As you go down the fractionating column, bear in mind that: the column temperature increases, the boiling point increases, the number of carbon atoms increases and the strength of the Van der Waals’ between molecules increases.

Different fractions have different usefulnesses and often, it is the fractions with lower boiling points and shorter chains which are much more purposeful. Therefore there needs to be a process to getting shorter chains because they are the least abundant in crude oil samples. To meet demand, long chain molecules that are less useful are broken down into shorter chain molecules. This is done by cracking.

Cracking is a process where long chain hydrocarbon molecules are broken down into shorter chain molecules which are in high demand. This can be done one of two ways - thermal or catalytic.

Thermal cracking involves heating long chain alkanes to high temperatures - usually between 1000 - 1200K. It also uses high pressures up to 70atm and takes just one second. It only needs a second because the conditions could decompose the molecule completely to produce carbon and hydrogen instead. The conditions produce shorter chain alkanes and mostly alkenes.

A typical equation for this:

Decane -> octane + ethene

C10H22 -> C8H18 + C2H4

Catalytic cracking also breaks down long alkanes by heat under pressure using the presence of a zeolite catalyst. Temperature used is approx. 800-1000K and the pressure is often between 1-2 atm. Zeolite is an acidic mineral with a honeycomb structure, made from aluminium oxide and silicion dioxide. The honeycomb structure gives the catalyst a larger surface area which increases ROR. Factories which catalytically crack are often operated continuously for around 3 years at a time and produce branched alkanes, cycloalkanes and aromatic compounds.

You need to be able to compare the conditions of catalytic and thermal cracking for the A Level exam. Know that thermal cracking has a high temperature and pressure, a short duration, no catalyst and produces a high percentage of alkenes and some short chain alkanes. Catalytic uses a catalyst, a high temperature, a low pressure and produces aromatic hydrocarbons and motor fuels.

SUMMARY

Crude oil contains carbon compounds formed by the effects of pressure and high temperature on plant and animal remnants. I It is a mixture of mainly alkane hydrocarbons which are separated by a process called fractional distillation.

Fractional distillation is the continual evaporation and condensation of a mixture which causes fractions to split due to a difference in boiling point.

It is important to note that fractional distillation does not separate crude oil into pure compounds but rather less complex mixtures.

Fractions are groups of compounds that have similar boiling points and are removed at the same level of a fractionating column.

The first step in this process is to heat crude oil in a furnace until some changes state from a liquid to a vapour. This mixture goes up a fractionating tower or column which is hotter at the bottom than the top and reaches a layer which is cool enough to condense and be collected. Shorter chain molecules are collected at the top where it is cooler since they have lower boiling points.

As you go down the fractionating column, bear in mind that: the column temperature increases, the boiling point increases, the number of carbon atoms increases and the strength of the Van der Waals’ between molecules increases.

Fractions with lower boiling points and shorter chains are much more purposeful but are the least abundant in crude oil samples. To meet demand, long chain molecules that are less useful are broken down into shorter chain molecules.

Cracking is a process where long chain hydrocarbon molecules are broken down into shorter chain molecules which are in high demand.

Thermal cracking involves heating long chain alkanes to high temperatures - usually between 1000 - 1200K. It also uses high pressures up to 70atm and takes just one second. It only needs a second because the conditions could decompose the molecule completely to produce carbon and hydrogen instead. The conditions produce shorter chain alkanes and mostly alkenes.

Catalytic cracking also breaks down long alkanes by heat under pressure using the presence of a zeolite catalyst. Temperature used is approx. 800-1000K and the pressure is often between 1-2 atm. Zeolite is an acidic mineral with a honeycomb structure, made from aluminium oxide and silicion dioxide. The honeycomb structure gives the catalyst a larger surface area which increases ROR.

You need to be able to compare the conditions of catalytic and thermal cracking for the A Level exam. Know that thermal cracking has a high temperature and pressure, a short duration, no catalyst and produces a high percentage of alkenes and some short chain alkanes. Catalytic uses a catalyst, a high temperature, a low pressure and produces aromatic hydrocarbons and motor fuels.

Happy studying!

Alkanes: Saturated Hydrocarbons

So you want to be an organic chemist? Well, learning about hydrocarbons such as alkanes is a good place to start…

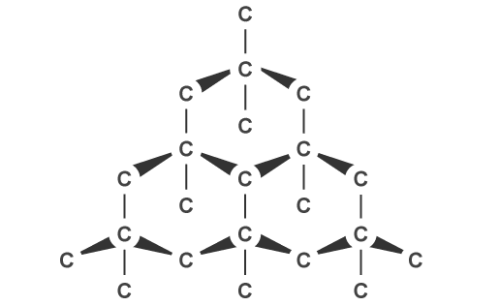

Alkanes are a homologous series of hydrocarbons, meaning that each of the series differs by -CH2 and that the compounds contain carbon and hydrogen atoms only. Carbon atoms in alkanes have four bonds which is the maximum a carbon atom can have - this is why the molecule is described to be saturated. Saturated hydrocarbons have only single bonds between the carbon atoms.

The general formula of an alkane is CnH2n+2 where n is the number of carbons. For example, if n = 3, the hydrocarbon formula would be C3H8 or propane. Naming alkanes comes from the number of carbons in the chain structure.

Here are the first three alkanes. Each one differs by -CH2.

Shorter chain alkanes are gases at room temperature, medium ones are liquids and the longer chain alkanes are waxy solids.

Alkanes have these physical properties:

1. They are non-polar due to the tiny difference in electronegativity between the carbon and hydrogen atoms.

2. Only Van der Waals intermolecular forces exist between alkane molecules. The strength of these increase as relative molecular mass increases therefore so does the melting/boiling point.

3. Branched chain alkanes have lower melting and boiling points than straight chain isomers with the same number of carbons. Since atoms are further apart due to a smaller surface area in contact with each other, the strength of the VDWs is decreased.

4. Alkanes are insoluble in water but can dissolve in non-polar liquids like hexane and cyclopentane. Mixtures are separated by fractional distillation or a separating funnel.

The fractional distillation of crude oil, cracking and the combustion equations of the alkanes will be in the next post.

SUMMARY

Alkanes are a homologous series of hydrocarbons. Carbon atoms in alkanes have four bonds which is the maximum a carbon atom can have - this is why the molecule is described to be saturated. Saturated hydrocarbons have only single bonds between the carbon atoms.

The general formula of an alkane is CnH2n+2 where n is the number of carbons.

Shorter chain alkanes are gases at room temperature, medium ones are liquids and the longer chain alkanes are waxy solids.

They are non-polar.

Only Van der Waals intermolecular forces exist between alkane molecules. The strength of these increase as relative molecular mass increases therefore so does the melting/boiling point.

Branched chain alkanes have lower melting and boiling points than straight chain isomers with the same number of carbons.

Alkanes are insoluble in water but can dissolve in non-polar liquids like hexane. Mixtures are separated by fractional distillation or a separating funnel.

Nomenclature - what in the organic chemistry is it?

Organic chemistry is so widely studied it requires a standard system for naming compounds, developed by IUPAC. Nomenclature is simply naming these organic compounds.

So, you want to be an organic chemist? Well, it starts here. Are you ready?

(psst… once you’ve learnt this theory, try a quiz here!)

1. Count your longest continuous chain of carbons.

Bear in mind that some chains may be bent. You’re looking for the longest chain of subsequent carbon atoms. This number correlates to root names that indicate the carbon chain length, listed below:

The second part of naming your base comes from the bonding in the chain. Is it purely single bonds or are there double bonds in there? If you are familiar with carbon chemistry, you’ll know that saturated hydrocarbons are called alkanes and unsaturated hydrocarbons are called alkenes. Therefore, the syllable -ane is used when it has only single bonds and the syllable -ene is used when it has some double bonds. For example:

Sometimes carbon chains exist in rings rather than chains. These have the prefix of -cyclo.

2. Identify your side chains attached to this main carbon and name them.

Side chains are added as prefixes to the root names. Sometimes called substituents, these are basically anything that comes off the carbon chain. Examples of the prefixes are listed below:

There are other prefixes such as fluoro (-F) and chloro (-Cl) which can describe what is coming off the chain.

3. Identify where each side chain is attached and indicate the position by adding a number to the name.

We aim to have numbers as small as possible. For example, if bromine is on the second carbon of a 5-carbon saturated chain, we number it as 2-bromopentane instead of 4-bromopentane, since it would essentially be 2-bromopentane if it was flipped. Locant is the term used for the number which describes the position of the substitute group, e.g. the ‘2′ in 2-chlorobutane is the locant.

Sometimes there are two or more side chains e.g. a methyl group and a chlorine attached to a pentane. In these cases, these rules apply:

1. Names are written alphabetically.

2. A separate number is needed for each side chain or group.

3. Hyphens are used to separate numbers and letters.

This would be named 2-chloro-3-methyl-pentane. This is because the longest chain of carbons is 5 (pentane), the chlorine is on the second carbon (2-chloro) and the methyl group is on the third carbon (3-methyl). It is 2-chloro rather than 4-chloro as we aim to have as small as numbers as possible.

Another variation of this step to be aware of is how many of the same side chains or groups there are, for example, having two methyl groups would be dimethyl rather than solely methyl. Each group must also be given numbers separated by commas to show where each one is located.

The list of these prefixes is found here:

Convention does not usually require mono- to go before a single group or side chain.

4. Number the positions of double bonds if applicable.

Alkenes and other compounds have double bonds. These must be indicated with numbers. For example, pent-2-ene shows that the double bond is between carbon 2 and carbon 3. The number goes in the middle of the original root name e.g. butene, pentene.

(!) Below is a list of functional groups that you may need to study for the AS and A Level chemistry exams. “R” represents misc. carbons. It is important to know that some groups are more prioritised than naming. From the most to least priority: carboxylic acid, ester, acyl chloride, nitrile, aldehyde, ketone, alcohol, amine, alkene, halogenalkane. It is worthwhile learning these.

bigger version here (I suggest downloading and printing it)

But wait, there’s more:

Here are some things to bear in mind when naming organic compounds:

1. The letter ‘e’ is removed when there are two vowels together e.g. propanone rather than propaneone. The ‘e’ isn’t removed when it is next to consonant, e.g. propanenitrile isn’t propannitrile.

2. When compounds contain two different, one is named as part of the unbranched chain and the other is named as a substituent. Which way round this goes depends on the priority.

SUMMARY

Count your longest continuous chain of carbons.

Chains may be bent. You’re looking for the longest chain of subsequent carbon atoms. This number correlates to root names that indicate the carbon chain length, e.g. pentane.

The second part of naming your base comes from the bonding in the chain. Is it purely single bonds or are there double bonds in there? The syllable -ane is used when it has only single bonds and the syllable -ene is used when it has some double bonds.

Rings have the prefix of -cyclo.

Identify your side chains attached to this main carbon and name them.

Side chains are added as prefixes to the root names. Sometimes called substituents, these are basically anything that comes off the carbon chain.

There are other prefixes such as fluoro (-F) and chloro (-Cl) which can describe what is coming off the chain.

Identify where each side chain is attached and indicate the position by adding a number to the name.

We aim to have numbers as small as possible. Locant is the term used for the number which describes the position of the substitute group, e.g. the ‘2′ in 2-chlorobutane is the locant.

Sometimes there are two or more side chains e.g. a methyl group and a chlorine attached to a pentane. In these cases, names are written alphabetically, a separate number is needed for each side chain or group and hyphens are used to separate numbers and letters.

When there are two or more of the same side chains or substituent groups, these must also be given numbers separated by commas to show where each one is located.

Number the positions of double bonds if applicable.

Alkenes and other compounds have double bonds. These must be indicated with numbers. The number goes in the middle of the original root name e.g. butene, pentene.

It is worthwhile learning the other functional groups that can be added on.They have varying priorities.

The letter ‘e’ is removed when there are two vowels together e.g. propanone rather than propaneone. The ‘e’ isn’t removed when it is next to consonant, e.g. propanenitrile isn’t propannitrile.

When compounds contain two different, one is named as part of the unbranched chain and the other is named as a substituent. Which way round this goes depends on the priority.

Happy studying guys!

Haloalkanes and Their Angelic Reactions: Part One

Haloalkanes are more commonly referred to as halogenoalkanes. Obviously you’ve already read my post on halogenoalkanes and their properties so there’s no surprise that you’re itching to read what I’ve got to say about these beauties and their reactions! Should we delve in?

There are a few different kinds of reactions you must learn for the A Level exam that involve halogenoalkanes.

The first is the synthesis of chloroalkanes via the photochemical chlorination of the alkanes. I know it looks scary, but don’t worry, it is simpler than it sounds. It essentially means “forming chloroalkanes through chlorinating an alkane in the presence of sunlight”.

Chlorine will react with methane when UV light is present and will form several kinds of chloroalkanes and fumes of hydrogen chloride gas. Chloromethane was once commonly used as a refridgerant. Depending on how many chlorine molecules there are, there will be different compounds formed:

methane + chlorine -> chloromethane + hydrogen chloride

CH4 + Cl2 -> CH3Cl + HCl

or

methane + chlorine -> trichloromethane + hydrogen chloride

CH4 + 3Cl2 -> CHCl3 + 3HCl

When undergone in real life, mixtures of halogenoalkanes are produced with some long chain alkanes which can be separated out with fractional distillation.

To understand what happens in an overall chemical reaction, chemists use mechanisms. These basically show the step-by-step process that is usually shown by a simple symbol equation that summarises everything.

The chlorination of methane is something you must learn the mechanism for. It’s pretty easy but involves a lot of steps and must be revised periodically to remember them.

The actual reaction is a substitution reaction because one atom or group is replaced by another. Since the chlorine involved is a free radical, it can also be called a free-radical substitution reaction.

1. Initiation

UV light is essential for the first step in the mechanism. This breaks the Cl-Cl covalent bond so that each chlorine leaves with one electron from the shared pair. Chlorine free radicals, with one unpaired electron in the outer shell, are formed. Free radicals are only formed if a bond splits evenly - each atom getting one of the two electrons. The name given to this is homolytic fission.

2. Propagation

This has two sub-steps

(a) Chlorine free radicals (highly reactive) react with methane to form hydrogen chloride and leave a methyl free radical.

Cl• + CH4 -> HCl + •CH3

(b) This free radical then reacts with another chlorine to form chloromethane and another chlorine free radical. Producing free radicals is a chain reaction which is why it is such a problem in ozone depletion - a little amount can cause a lot of destruction.

•CH3 + Cl2 -> CH3Cl + •Cl

3. Termination

This step stops the chain reaction. It only happens when two free radicals collide to form a molecule in several ways:

Cl• + Cl• -> Cl2

UV light would just break down the chlorine molecule again, so although this is technically a termination reaction it is not the most efficient.

Cl• + •CH3 -> CH3Cl

Forming one molecule of methane uses one chlorine and one methyl free radical.

•CH3 + •CH3 -> C2H6

Ethane can be formed from two methyl free radicals - this is why there are longer chain alkanes in the mixture.

This whole process is how organic halogenoalkanes are the product of photochemical reactions of halogens with alkanes in UV light - made via free radical substitution mechanisms in chain reaction.

Another reaction you need to know is a nucleophilic substitution reactions. A nucleophile is an electron pair donor or proton acceptor - the name comes from Greek origins (”loves nucleus”) - such as hydroxide ions, cyanide ions or ammonia molecules. Hydroxide and cyanide ions are negative but ammonia is neutral.

Halogenoalkanes have a polar bond because of the difference between the highly electronegative halogen and the carbon atom. The 𝛿+ carbon can go under nucleophilic attack. The mechanism for negatively charged nucleophiles these in general is:

Nu represents the nucleophile. This example is with a bromoalkane. Make sure to include curly arrows that begin at a lone pair or the centre of a bond and end at an atom or centre of bond, and delta (slight) charges.

Lets look at a more specific example:

One nucleophile that can be used is a hydroxide ion, found in either water or sodium hydroxide. In this case, you need to know about aqueous sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide and a halogenoalkane. This takes place at room temperature but is slow so is often refluxed (continuously boiled and condensed back into the reaction flask). Reflux apparatus is shown below:

The halogenoalkane is dissolved into ethanol since it is insoluable in water and this solution along with the aqueous hydroxide can mix. The product produced is an alcohol, which is organic.

The general reaction is:

R-CH2X + NaOH -> CH3CH2OH + NaX

Where X represents a halogen.

You must learn the mechanism for this reaction. The lone pair on the hydroxide attacks the carbon atom attached to the halogen and this causes both carbon electrons to move to the halogen which becomes a halide ion.

The reaction of a hydroxide ion can also be classed as a hydrolysis reaction as it breaks down chemical bonds with water or hydroxide ions. The speed of reaction depends on the strength of the bond - a stronger carbon-halogen bond, a slower reaction.

C-I is the most reactive (reactivity increases down group 7) and C-F is therefore the least reactive and strongest.

Part two of this post will cover nucleophilic substitution of cyanide ions and ammonia molecules, as well as elimination reactions.

SUMMARY

You need to know about the synthesis of chloroalkanes via the photochemical chlorination of the alkanes. - “forming chloroalkanes through chlorinating an alkane in the presence of sunlight”.

Chlorine will react with methane when UV light is present and will form several kinds of chloroalkanes and fumes of hydrogen chloride gas. Depending on how many chlorine molecules there are, there will be different compounds formed.

When undergone in real life, mixtures of halogenoalkanes are produced with some long chain alkanes which can be separated out with fractional distillation.

To understand what happens in an overall chemical reaction, chemists use mechanisms. These basically show the step-by-step process.

The chlorination of methane is something you must learn the mechanism for. The actual reaction is a substitution reaction because one atom or group is replaced by another.

The first step is initiation - UV light is essential for the first step in the mechanism. This breaks the Cl-Cl covalent bond so that each chlorine leaves with one electron from the shared pair. Chlorine free radicals, with one unpaired electron in the outer shell, are formed. Free radicals are only formed if a bond splits evenly - each atom getting one of the two electrons.

Step two is propagation: (a) Chlorine free radicals (highly reactive) react with methane to form hydrogen chloride and leave a methyl free radical (b) this free radical then reacts with another chlorine to form chloromethane and another chlorine free radical. Producing free radicals is a chain reaction which is why it is such a problem in ozone depletion - a little amount can cause a lot of destruction.

To stop the chain reaction, the final step is termination. It only happens when two free radicals collide to form a molecule in several ways: two chlorine free radicals forming a chlorine molecule, two methyl FRs forming ethane or a chlorine FR and a methyl FR forming chloromethane.

Ethane contributes to the longer chain alkanes in the mixture.

Another reaction you need to know is a nucleophilic substitution reactions. A nucleophile is an electron pair donor or proton acceptor, such as hydroxide ions, cyanide ions or ammonia molecules. Hydroxide and cyanide ions are negative but ammonia is neutral.

Halogenoalkanes have a polar bond because of the difference between the highly electronegative halogen and the carbon atom. The 𝛿+ carbon can go under nucleophilic attack.

Nu represents the nucleophile. Make sure to include curly arrows that begin at a lone pair or the centre of a bond and end at an atom or centre of bond, and delta (slight) charges.

One nucleophile that can be used is a hydroxide ion, found in either water or sodium hydroxide. In this case, you need to know about aqueous sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide and a halogenoalkane. This takes place at room temperature but is slow so is often refluxed (continuously boiled and condensed back into the reaction flask). The halogenoalkane is dissolved into ethanol since it is insoluable in water and this solution along with the aqueous hydroxide can mix. The product produced is an alcohol, which is organic.

The general reaction is :R-CH2X + NaOH -> CH3CH2OH + NaX where X represents a halogen

The lone pair on the hydroxide attacks the carbon atom attached to the halogen and this causes both carbon electrons to move to the halogen which becomes a halide ion.

The reaction of a hydroxide ion can also be classed as a hydrolysis reaction as it breaks down chemical bonds with water or hydroxide ions.

The speed of reaction depends on the strength of the bond - a stronger carbon-halogen bond, a slower reaction. C-I is the most reactive (reactivity increases down group 7) and C-F is therefore the least reactive and strongest.

Halogenoalkanes

Halogenoalkanes are a homologous series of saturated carbon compounds that contain one or more halogen atoms. They are used as refrigerants, solvents, flame retardants, anaesthetics and pharmaceuticals but their use has been restricted in recent years due to their link to pollution and the destruction of the ozone layer.

They contain the functional group C-X where X represents a halogen atom, F,Cl, Br or I. The general formula of the series is CnH2n+1X.

The C-X bond is polar because the halogen atom is more electronegative than the C atom. The electronegativity decreases as you go down group 7 therefore the bond becomes less polar. Flourine has a 4.0 EN whereas iodine has a 2.5 EN meaning it is almost non-polar.

The two types of intermolecular forces between halogenoalkane molecules are Van Der Waals and permanent dipole-dipole interactions. As the carbon chain length increases, the intermolecular forces (due to VDWs) increase as the relative atomic mass increases due to more electrons creating induced dipoles. Therefore the boiling point of the halogenoalkanes increases since more forces must be broken.

Branched chains have lower boiling points than chains of the same length and halogen because the VDWs are working across a greater distance and are therefore weaker.

When the carbon chain length is kept the same, but the halogen atom is changed, despite the effect of the changing polar bond on the permanent dipole-dipole interactions, the changing VDWs have a greater effect on the boiling point. Therefore as RAM increases, the boiling point increases meaning an iodoalkane has a greater boiling point than a bromoalkane if they have the same carbon chain length.

Halogenoalkanes are insoluble or only slightly soluable in water despite their polar nature. They are soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol and can be used as dry cleaning agents because they can mix with other hydrocarbons.

Summary

Halogenoalkanes are saturated carbon compounds with one or more halogen atoms. Their general formula is CnH2n+1X, where X is a halogen. Their functional group is therefore C-X.

They are used as refrigerants, solvents, pharmaceuticals and anaesthetics but have been restricted due to their link to the depletion of the ozone layer.

C-X bonds are polar due to the halogen being more electronegative than the carbon. The polarity of the bond decreases down group 7.

Van der Waals and permanent dipole-dipole interactions are the intermolecular forces in halogenoalkanes.

When carbon chain length increases, boiling points increase due to RAM increasing and the number of Van Der Waals increasing too.

In branched halogenoalkanes, Van Der Waals are working across a greater distance therefore attraction is weaker and boiling points are lower than an identical unbranched chain.

When the halogen is changed, the boiling point increases down the group due to the effect of a greater RAM - more VDWs mean more intermolecular forces to break.

Halogenoalkanes are insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents like ethanol.

Bonus: free radical substitution reactions in the ozone layer

Ozone, O3, is an allotrope of oxygen that is usually found in the stratosphere above the surface of the Earth. The ozone layer prevents harmful rays of ultraviolet light from reaching the Earth by enhancing the absorption of UV light by nitrogen and oxygen. UV light causes sunburn, cataracts and skin cancer but is also essential in vitamin D production. Scientists have observed a depletion in the ozone layer protecting us and have linked it to photochemical chain reactions by halogen free radicals, sourced from halogenoalkanes which were used a solvents, propellants and refrigerants at the time.

CFCs cause the greatest destruction due to their chlorine free radicals. CFCs – chloroflouroalkanes – were once valued for their lack of toxicity and their non-flammability. This stability means that they do not degrade and instead diffuse into the stratosphere where UV light breaks down the C-Cl bond and produces chlorine free radicals.

RCF2Cl UV light —> RCF2● + Cl●

Chlorine free radicals then react with ozone, decomposing it to form oxygen.

Cl● + O3 —> ClO● + O2

Chlorine radical is then reformed by reacting with more ozone molecules.

ClO● + O3 —-> 2O2 + Cl●

It is estimated that one chlorine free radical can decompose 100 000 molecules of ozone. The overall equation is:

2O3 —-> 3O2

200 countries pledged to phase of the production of ozone depleting agents in Montreal, leading to a search for alternatives. Chemists have developed and synthesised alternative chlorine-free compounds that do not deplete the ozone layer such as hydroflurocarbons (HFCs) like trifluromethane, CHF3.

SUMMARY

Ozone, found in the stratosphere, protects us from harmful UV light which can cause cataracts, skin cancer and sunburn.

Ozone depletion has been linked to the use of halogenoalkanes due to their halogen free radicals.

CFCs were good chemicals to use because they have low toxicity and were non-flammable. The fact they don’t degrade means they diffuse into the stratosphere.

Chlorine free radicals are made when CFCs are broken down by UV light.

These go on to react with ozone to produce oxygen.

Chlorine free radicals are then reformed by reacting with more ozone.

It is a chain reaction that can deplete over 100 000 molecules of ozone.

There is a 200 country ban on their use and scientists have developed alternatives like hydrofluorocarbons to replace them

Happy studying!

Metallic Bonding

A short one to finish off my first ever mini-series on bonding – ionic, covalent and finally metallic. There are metallic and metallic compounds and elements but for the A Level exam, we must look at the bonding within metals themselves. Don’t worry – I saved the easiest to last!

Metals are most usually solid so have particles packed close together. These are in layers which mean that the outer electrons can move between them rather than being bound to particular atoms. These are referred to as delocalised electrons because of this.

It’s pretty common knowledge that metals are good conductors of heat and electricity and it’s these delocalised electrons that give them this property.

Metals are therefore without their electrons so become positive ions. The metallic bond is actually the attraction between delocalised electrons and positive metal ions in the lattice. And that’s pretty much metallic bonding, you just need to know the properties of metals which are touched upon at lower levels of education.

These are the properties of metals:

1. High melting points

Metals have large regular structures with strong forces between the oppositely charged positive ions and negative electrons, meaning these must be overcome to melt the metal – this requires a large amount of heat energy. Transition metals tend to have higher melting points than the main group metals because they have large numbers of d-shell electrons which can become delocalised creating a stronger metallic bond. Melting points across a period increase because they can have progressively more delocalised electrons: Na+, Mg 2+ and Al 3+ for example.

2. Heat conductivity

Heat is conducted if particles can move and knock against each other to pass it on. Delocalised electrons allow this to happen. Silver is a particularly good conductor of heat.

3. Electrical conductivity

Delocalised electrons can carry charge and move, the two requirements of electrical conductivity. Current can flow because of these delocalised electrons.

4. Ductile and malleable

Metals can be stretched and hammered into shape, making them ideal for things such as wires. Layered lattices mean that layers can slide over each other without disrupting the bonding – it is all still held together by the delocalised electrons and their strong attraction to the positive metal ions.

5. High densities

Being a solid, metal ions are packed closely together so they have a high density, which makes them ideal for musical instrument strings. These can withstand the frequency of vibration whilst also being thinner.

SUMMARY

Metals are solid so have particles packed close together. These are in layers which mean that the outer electrons can move between them rather than being bound to particular atoms. These are referred to as delocalised electrons because of this.

Metals are therefore without their electrons so become positive ions. The metallic bond is actually the attraction between delocalised electrons and positive metal ions in the lattice.

Metals have high melting points.

Metals have large regular structures with strong forces between the oppositely charged positive ions and negative electrons, meaning these must be overcome to melt the metal – this requires a large amount of heat energy. Transition metals tend to have higher melting points than the main group metals because they have large numbers of d-shell electrons which can become delocalised creating a stronger metallic bond.

Metals conduct heat.

Heat is conducted if particles can move and knock against each other to pass it on. Delocalised electrons allow this to happen.

Metals have good electrical conductivity

Delocalised electrons can carry charge and move, the two requirements of electrical conductivity. Current can flow because of these delocalised electrons.

Metals are ductile and malleable.

Metals can be stretched and hammered into shape, making them ideal for things such as wires. Layered lattices mean that layers can slide over each other without disrupting the bonding – it is all still held together by the delocalised electrons and their strong attraction to the positive metal ions.

Being a solid, metal ions are packed closely together so they have a high density.

Happy studying!

Covalent Bonds: Sharing Is Caring!

Welcome to my second out of three posts on bonding - ionic, covalent and metallic. This post also covers the coordinate/ dative bond which I can’t remember if I’ve covered before. Only one more of this series left! Find the others here.

Covalent bonding involves one or more shared pairs of electrons between two atoms. These can be found in simple molecular elements and compounds like CO2 , macromolecular structures like diamond and molecular ions such as ammonium. Covalent bonds mostly occur between non-metals but sometimes metals can form covalent bonds.

Single covalent bonds share just one pair of electrons. Double covalent bonds share two. Triple covalent bonds share three.

Each atom usually provides one electron – unpaired in the orbital – in the bond. The number of unpaired electrons in an atom usually shows how many bonds it can make but sometimes atoms promote electrons to fit in more. Covalent bonds are represented with lines between the atoms – double and triple bonds represented with two and three lines respectively.

Dot and cross diagrams show the arrangement of electrons in covalent bonds. They use dots and crosses to demonstrate that the electrons come from different places and often only the outer shell is shown.

The simple explanation as to how atoms form covalent bonds is that one unpaired electron in the orbital of one atom overlaps with one in another atom. Sometimes atoms promote electrons in the same energy level to form more covalent bonds. For example, if an atom wants to make three covalent bonds but has a full 3s2 shell and a 3p1 shell, it can promote one of its 3s2 electrons so that an electron from the other atoms can fill the 3s shell and pair with the new 3p2 shell.

Sometimes promotion does not occur and that means different compounds can be made such as PCl3 or PCl5.

A lone pair of electrons is a pair of electrons from the same energy sub-level uninvolved in bonding. Sometimes these can form something called a coordinate bond, which contains a shared pair of electrons where both come from one atom. The lone pair of electrons is “donated” into the empty orbital of another atom to form a coordinate bond.

This is an example of a coordinate (sometimes called dative) bond between ammonia and a H+ ion which has an empty orbital. The lone pair on the ammonia overlaps with this H+ ion and donates its electrons. Both electrons come from the ammonia’s lone pair so it is a coordinate bond. This is demonstrated with an arrow. The diagram is missing an overall charge of + on the ammonium ion it produces. Coordinate bonds act the same as covalent bonds.

Once you have your covalent bonds, you need to know about covalent substances and their properties. There are two types of covalent substance: simple covalent (molecular) and macromolecular (giant covalent).

Molecular simply means that the formula for the compound or element describes exactly how many atoms are in one molecule, e.g. H2O. Molecular covalent crystalline substances usually exist as single molecules such as iodine or oxygen. They are usually gases or liquids at room temperature but can be low melting point solids.

Solid molecular covalent solids are crystalline so can be called molecular covalent crystals. Iodine and ice are examples of these. Iodine (shown below) has a regular arrangement which makes it a crystalline substance and water, as ice, has a crystalline structure as well.

The properties of these crystals are that they have low melting points, are very brittle due to the lack of strong bonds holding them together and also do not conduct electricity since no ions are present.

The other kind of covalent substance you need to know is macromolecular. This includes giant covalent structures such as diamond or graphite, which are allotropes of carbon. Non-metallic elements and compounds usually form these crystalline structures with a regular arrangement of atoms.

Allotropes are different forms of the same element in the same physical state.

Diamond is the hardest naturally occurring substance on earth therefore is good for cutting glass and drilling and mining. It has a high melting point due to the many covalent bonds which require a lot of energy to break. Each carbon has four of these bonds joining it to four others in a tetrahedral arrangement with a bond angle of 109.5 degrees and it does not conduct electricity or heat because there are no ions free to move.

Graphite, on the other hand, can conduct electricity. This is because it has delocalised electrons between the layers which move and carry charge. Carbon atoms within the structure are only bonded to three others in a hexagonal arrangement with a bond angle of 120 degrees. Since only three of carbon’s unpaired electrons are used in bonding, the fourth becomes delocalised and moves between the layers of graphite causing weak attractions, explaining why it can conduct electricity.

Graphite’s layered structure and the weak forces of attractions between it make it a good lubricant and ideal for pencil lead because the layers can slide over each other. The attractions can be broken easily but the covalent bonds within the layers give graphite a high melting point due to the amount of energy needed to break them.

SUMMARY

Covalent bonding involves one or more shared pairs of electrons between two atoms. Covalent bonds mostly occur between non-metals but sometimes metals can form covalent bonds.

Single covalent bonds share just one pair of electrons. Double covalent bonds share two. Triple covalent bonds share three.

Each atom usually provides one electron – unpaired in the orbital – in the bond. The number of unpaired electrons in an atom usually shows how many bonds it can make but sometimes atoms promote electrons to fit in more. Covalent bonds are represented with lines between the atoms.

Dot and cross diagrams use dots and crosses to demonstrate that the electrons come from different places and often only the outer shell is shown.

The simple explanation as to how atoms form covalent bonds is that one unpaired electron in the orbital of one atom overlaps with one in another atom. Sometimes atoms promote electrons in the same energy level to form more covalent bonds.

Sometimes promotion does not occur and that means different compounds can be made such as PCl3 or PCl5.

A lone pair of electrons is a pair of electrons from the same energy sub-level uninvolved in bonding. Sometimes these can form something called a coordinate bond, which contains a shared pair of electrons where both come from one atom. The lone pair of electrons is “donated” into the empty orbital of another atom to form a coordinate bond.

The formation of ammonium is an example of this.

There are two types of covalent substance: simple covalent (molecular) and macromolecular (giant covalent).

Molecular simply means that the formula for the compound or element describes exactly how many atoms are in one molecule, e.g. H2O. Molecular covalent crystalline substances usually exist as single molecules such as iodine or oxygen. They are usually gases or liquids at room temperature but can be low melting point solids.

Solid molecular covalent solids are crystalline so can be called molecular covalent crystals. Iodine and ice are examples of these.

The properties of these crystals are that they have low melting points, are very brittle due to the lack of strong bonds holding them together and also do not conduct electricity since no ions are present.

Giant covalent structures such as diamond or graphite are allotropes of carbon. Allotropes are different forms of the same element in the same physical state.

Diamond has a high melting point due to the many covalent bonds which require a lot of energy to break. Each carbon has four of these bonds joining it to four others in a tetrahedral arrangement with a bond angle of 109.5 degrees and it does not conduct electricity or heat because there are no ions free to move.

Graphite can conduct electricity. This is because it has delocalised electrons between the layers which move and carry charge. Carbon atoms within the structure are only bonded to three others in a hexagonal arrangement with a bond angle of 120 degrees. Since only three of carbon’s unpaired electrons are used in bonding, the fourth becomes delocalised and moves between the layers of graphite causing weak attractions, explaining why it can conduct electricity.

Graphite’s layered structure and the weak forces of attractions between it make it a good lubricant and ideal for pencil lead because the layers can slide over each other. The attractions can be broken easily but the covalent bonds within the layers give graphite a high melting point due to the amount of energy needed to break them.

Happy studying!

The Name’s Bond ... Ionic Bond.

This is the first in my short series of the three main types of bond - ionic, metallic and covalent. In this, you’ll learn about the properties of the compounds, which atoms they’re found between and how the bonds are formed. Enjoy!

When electrons are transferred from a metal to a non-metal, an ionic compound is formed. Metals usually lose electrons and non-metals usually gain them to get to a noble gas configuration. Transition metals do not always achieve this.

Charged particles that have either lost or gained electrons are called ions and are no longer neutral - metal atoms lose electrons to become positive ions (cations) whereas non-metals gain electrons to become negative ions (anions).

The formation of these ions is usually shown using electron configurations. Make sure you know that the transfer of electrons is not the bond but how the ions are formed.

An ionic bond is the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions.

You need to know how to explain how atoms react with other atoms and for this the electron configurations are needed. You can use dot and cross diagrams for this.

Ionic solids hold ions in 3D structures called ionic lattices. A lattice is a repeating 3D pattern in a crystalline solid. For example, NaCl has a 6:6 arrangement - each Na+ ion is surrounded by 6 Cl- and vice versa.

Ionic solids have many strong electrostatic attractions between their ions. The crystalline shape can be decrepitated (cracked) on heating. Ionic Lattices have high melting and boiling points since they need more energy to break because atoms are held together by lots of strong electrostatic attractions between positive and negative ions. The boiling point of an ionic compound depends on the size of the atomic radius and the charge of the ion. The smaller the ion and the higher the charge, the stronger attraction.

Look at this diagram. It shows how atomic radius decreases across a period regularly. This is not the case with the ions. Positive ions are usually smaller than the atoms they came from because metal atoms lose electrons meaning the nuclear charge increases which draws the electrons closer to the nucleus. For negative ions, they become larger because repulsion between electrons moves them further away - nuclear charge also decreases as more electrons to the same number of protons.

Ionic substances can conduct electricity through the movement of charged particles when molten or dissolved (aqueous). This is because when they are like this, electrons are free to move and carry a charge. Ionic solids cannot conduct electricity.