Latest Posts by happyzoneartlover - Page 3

Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová

Aesthetic emotion puts man in a state favourable to the reception of erotic emotion. Art is the accomplice of love. Take love away and there is no longer art.

- Remy de Gourmont

william larson

John Chervinsky

source

Escheresque- modern house allows flow by Berlin Wall memorial. video: youtube: Kirsten Dirksen

When Helle Schröder and Martin Janekovic (XTH-Berlin) signed a 199-year lease on some land along the old Berlin Wall, they had a permit to build a row house, but despite the two shared walls, they wanted something that felt airy and light-filled. ( text: Kirsten Dirksen)

Young Architect Guide: 12 Common Mistakes Made When Drawing Architecture

Send us a drawing, tell us a story, win $2,500! Call for entries begins June 10th. Register for the One Drawing Challenge today.

This summer’s One Drawing Challenge poses the simple question — can you tell a powerful story about architecture in a single drawing? As these 10 iconic drawings illustrate, it’s completely possible to do just that, and, in the process, fundamentally change how we think about the built environment.

That said, our efforts to communicate through drawings can fall short if mistakes are made in the creation process. There are plenty of great guides that explain how to draw architecture in a clear, compelling manner, but not so many that talk about what not to do. As you prepare your entry for this year’s One Drawing Challenge, take heed of these common mistakes and be inspired by the exemplary drawings shown to put your best foot forward for the competition:

Well planned architectural illustrations by Giuliana Flavia Cangelosi; via Instagram

1. Drawing without a plan

Putting pencil or pen to paper without having an end goal in sight is particularly common in architecture because we tend to confuse visual brainstorming with total improvisation. Even if you are creating conceptual sketches, you should ask yourself key questions about your desired outcome before you begin.

How many concepts are you aiming for? How much detail are you going to include? Are you thinking about a concept in 2D, 3D or both? Miriam Slater of Empty Easel states that “more often than not, people immediately begin sketching without establishing some kind of intention in their mind first. You’ll find that a well-thought out drawing always seems more focused and clearer than one that doesn’t.”

2. Relying too much on outlines

While lines work well for diagrammatic drawings, their use should be carefully considered when sketching out a perspective street scene or natural environment. “Every time we touch a drawing tool to paper it desires to make a line,” says John Morfis of Hello Artsy, “but the real world does not contain any outlines.” The trick, according to Morfis, is to view the world in terms of values — levels of light and shade — and use these to define the edges of buildings and other objects in the drawing.

3. Focusing on details too soon

With architectural drawings, the overall composition and structure of a drawing is vital — without a solid foundation in these areas, no amount of detail will save you. “It is very easy to get lost in the details,” explains Slater, “but all that work goes to waste unless you have the proper larger forms in first.

“The temptation is to start ‘finishing off’ the drawing too fast, resulting in some beautifully rendered areas that have to be erased later. Get the drawing laid in correctly from the start, always remembering to work from large to small. The main forms go in first, followed by the details that can be considered icing on the cake.”

Drawing for Museo Neanderthal by Barozzi Veiga; image via Barozzi Veiga

4. Inconsistent illumination

Following on from the previous mistake, applying the correct lighting throughout an architectural perspective or section drawing is crucial in achieving a realistic scene. “We see because of light,” says Morfis. “Don’t forget to hint at a light source in your drawing. This means that one side of an object will generally be lighter or darker than another side.

“For example, perhaps the top of all of your objects should be depicted as the lightest.” Regardless of where you place your light source, the key is consistency — if your shadows do not run parallel with each other in the appropriate places, your drawing will instantly look wrong.

5. Not utilizing line weights

If there is one guaranteed way to make your architectural drawings look lifeless or lack clarity, it’s neglecting to vary the thickness or shade of your lines. “A diversity of line styles and weights allows you to distinguish depth and emphasize different parts of a drawing,” explains Eric Baldwin in his guide to architectural drawing. “A drawing can quickly read as flat when only a single type of line is used on a sketch or projection.”

6. Using an unnatural perspective

Architectural visualization expert Alex Hogrefe explained the importance of perspective in his article “7 Rules for Composing Powerful Architectural Perspectives.” While Hogrefe is in the business of renderings, his rules apply to drawings too. “If you are going to create an eye-level view, set the camera height to around 6 feet to better connect the viewer to the experience of being at that space,” explains Hogrefe. “People often rationalize that they want to better see the ground plane, so they raise the camera to just above head height at 8, 10, 12 feet, etc. However, this makes for an awkward and uncomfortable composition.”

Pencil drawing for the Vara Pavilion by Mauricio Pezo and Sofia von Ellrichshausen; image via Dezeen

7. Drawing circular forms incorrectly

Most people are pretty adept at drawing two point perspectives — as long as the forms remain straight-edged. As soon as you introduce a curved façade or a circular window into the mix, things get complicated — and often rather distorted. “Viewed from any other angle other than straight on, a circular shape should be drawn as a ellipse,” says Morfis. “This will account for the proper perspective necessary to create effective illusions of form and space within your artwork.” Hello Artsy’s simple guide to drawing ellipses is a great starting point.

8. Smudging

It’s a drawing problem everyone has faced at some point in their life — you begin to shade in shadows with your pencil, and before you know it, there are black marks on your hand and across your paper.

The best way to avoid this scenario is to plan ahead — develop your drawing in such a way that you never have to lean the heel of your hand on parts you have already drawn. For larger drawings, sometimes you have to but your hand somewhere, but fortunately there are tools to help you — you can lean on a mahl stick or drawbridge to elevate your hand while you work.

9. Neglecting texture and pattern

Oftentimes, architects view every drawing as a clean diagram, and while this approach can be appropriate for certain drawing types, texture and pattern are ignored at your peril. Why? Because, as Eric Baldwin points out, “texture can be the primary means of telling a story in a drawing.”

While hatching can be vital in identifying different parts of a technical construction details, more conceptual drawings are aided by a creative approach to pattern and texture. “Varied densities of texture can create movement and pattern, defining their own forms of reading,” says Baldwin.

A correct use of shading can add a strong three-dimensional quality to your drawings; image via My Modern Met

10. Using the wrong grade of pencil

If you are attempting to create depth in an architectural perspective drawing, selecting pencils with varied graphite grades is essential. If your pencil is too hard, you will not achieve the desired contrast between light and dark areas of your scene.

In the U.S, the graphite grading scale is numeric. The hardness of the core is often marked on the pencil — look for a number (such as “2” “2-1/2” or “3”). The higher the number, the harder the graphite core and the lighter the mark left on the paper. As the pencil core becomes softer, it leaves a darker mark as it deposits more graphite material on the paper. Bear in mind that softer pencils dull faster than harder pencils and require more frequent sharpening.

11. Using poor materials

You can have all the skill in the world, but it all counts for nothing if you use a blunt pencil, a blotchy pen or smudging eraser. Invest in good quality tools to ensure that your drawings are sharp, clean an full of contrast, just the way you envisioned them. “Quality drawing tools will give you’re a broader range of mark-making ability and be more forgiving,” says Morfis. “If you are going to spending time learning how to draw, please treat yourself to the best supplies that you can afford. Good art supplies may seem expensive but you’ll get countless hours of use from them.”

12. Having a fixed mentality

Drawing, like any aspect of architectural design, is challenging, and takes persistence practice to master. There is always a danger in any artistic pursuit to view this challenge as insurmountable. However, with patience, mastery is possible for everyone. “So many students look at someone who seems to have more skill then themselves and decide that they are not talented,” says Morfis. “They have then locked their own mental state into a level that determines that they will never be any good at drawing. This form of self-defeatism is a tragedy and unfortunately very common in the field of visual arts.

“The truth is: drawing CAN be learned, and if you’re aware of common drawing mistakes, you’ll learn to draw even faster! Studies show that people tend to be good at something because they took an interest in something at a young age and were allowed to thrive in an environment that nurtured the interest. It takes practice and learning. If you are willing to learn and willing to practice you can learn anything … even drawing!”

Now show us what you can do: Register for the One Drawing Challenge and submit your best architectural drawing for a chance to win $2,500!

Register for the One Drawing Challenge

The post Young Architect Guide: 12 Common Mistakes Made When Drawing Architecture appeared first on Journal.

Paul Keskeys via Journal http://bit.ly/2I97X1S

Detached Floor House / Jun Yashiki & Associates

module K blends indochine and modernist elements for a mixed use building in vietnam

Yasuhiro Yamashita x Atelier TEKUTO. Boltun Headquarters. Warabi City, Saitama. Japan. photos: Toshihiro Sobajima

- “CONCEPTION” - . As the main obstruction to be relinquished, has the basic sense of “constructing” “forming” “manufacturing” or, “inventing.” Thus in terms of mind, they mean “creating in the mind”, forming in the “imagination,” and even “assuming to be real,” “feigning,” and “fiction.” Fundamentally, these terms refer to the continuous constructive yet deluded activity of the mind that never tires of producing all kinds of dualistic appearances and experiences, thus literally building its own world. . A concept is something conceived in the mind: Thought, Idea, Notion. About “conceive”, Webster dictionary says; ‘to take into one’s mind… To form in one’s mind… To evolve mentally… IMAGINE, VISUALISE. This meaning of deluded mental activity is particularly highlighted by the classical Yogãcãra terms “false imagination” and “the imaginary,” the latter being everything that appears as the division into Subject and Object that is produced by false imagination. . In a more general sense, “imagination” and “concept” are equivalent, which is also what Nãgãjuna’s Cittavajrastava (verse 5) means: ’[For] the mind that has given up imagination, Samsãra impregnated by imagination Is nothing but an imagination — The lack of imagination is Liberation.’ . Obviously, this does not mean that samsãra is nothing but conceptual thinking or that mere lack of thinking is nirvana. False imagination is threefold — 1st) consisting of mere appearance, under the sway of latent tendencies, of apprehender and apprahdended being different; 2nd) those that have aspects of coarse states of mind; 3rd) is clinging to reference through following names, false views, conventional reality. . Thus, conceptions about “Apprehender and "Apprehended” in all their coarse and subtle degrees represent the cognitive obstructions to be relinquished throughout the Path of preparation, seeing, and familiarisation of these CONCEPTS. . #Buddha #Buddhism #dharma #wisdom #Knowledge #Enlightenment #awakening #Consciousness #meditation #meditator #namaste #yogalife #Spiritual #peace #illusion #happiness #mental #alchemy #loveandlight #goodvibrations #positvevibes #blogger #sunday #concept #art #health

Rose House | Sergey Makhno Architects Location: Carpathian Mountains, Ukraine

Brancusi, April 2018 https://www.instagram.com/p/BtLY8CRHREV/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1p2brlbsd605v

by @oparchland #next_top_architects in #NEXTarch We Trust

// A stray Gable / wip from a silly submission with @and.either.or / type roof outforawalk

Developed by @basovervelde - 2017 Nature paper ‘Reconfigurable Materials’ Overvelde, Bertoldi, Hoberman and Weaver

Young Architect Guide: How to Sell Yourself With a Story

Architects: Showcase your work and find the perfect materials for your next project through Architizer. Manufacturers: To connect with the world’s largest architecture firms, sign up now.

The world of architecture is small and narrow. Proportionally, there aren’t many people working in it who aren’t architects — which makes it especially difficult to break into in a satisfying way for the young or those just graduating from school. Even with the requisite education and entry-level experience, getting a job in the profession is an uphill battle for the simple reason that nearly everyone applying for an open position wants the same thing: a job as an architect.

From the viewpoint of those doing the hiring, this makes it equally difficult to decide exactly who to hire, because many young architects’ portfolios begin to look the same after repeatedly viewing hundreds of them. With this in mind, standing out in a pile of submissions at an office you want to work for becomes a primary concern.

How do you do this? There’re many ways, but one I’ve found to be fairly effective is to craft a cohesive, easily discernible theme for yourself that differentiates your application from all the others. This theme is the story that ties together all the work, presentation and correspondence you’re sharing with whoever may be hiring, and it’s the thoroughness and consistency of this theme (combined with what it means to the office or architect you’re submitting to) that can effectively sell your application.

Thus, when looking for a job in architecture, it follows to first develop this theme or story, then craft your approach and application materials to clearly reflect it.

Architecture portfolio via arch2o

Think Outside Architecture

Uncovering a good, unifying story that applies to all the work you’ve done starts with an introspective search for something you know, do or feel that you don’t recognize in any other architect — then turning it into a storytelling hook that can capture and sustain interest. The method of this process can vary widely from person to person, but in each case it fundamentally involves identifying the things you do or have done that aren’t architecture. Nearly anything you studied in school outside the architecture curriculum or any job you’ve had that wasn’t in an architecture firm is a good place to start. If you have a master’s degree in architecture with a background in another field, then that area is likely prime territory to draw from.

For example, maybe you have an interest in high-level mathematics, with something on paper to back it up. In terms of evidence, a professional degree or working experience in this interest is great but not necessary, because something as basic as a few classes, a workshop or a club will suffice as the origin of the story and its corresponding line toward the top of a resume. The real challenge for developing this story is applying it to the work in your architecture portfolio.

Architecture portfolio box by Ashley Mayes

Frame, Don’t Fabricate

Trying to retroactively present projects you’ve completed over the course of several years as if they were always planned to fit into an all-encompassing theme is preposterous because you almost certainly didn’t complete the work with that theme in mind. But if you understand that the strategy detailed here is about framing, not fabrication, then you’re well on your way to discovering a theme.

To that end, if you’ve identified an interest or activity that’s truly important to you, it probably shows up throughout your work in places you weren’t aware of before. For the high-level mathematics enthusiast, a studio project composed of a series of proportional volumes suddenly takes on new importance when they realize the architectural forms illustrated in their portfolio can now be notated to express the underlying ratios behind them — a reverse-engineered revision with the benefit of being unusual while also supporting their theme.

Sample portfolio pages via Alex Hogrefe

Follow Through With Your Theme

Once you’ve identified and developed a strong theme for yourself, the second part of this task in a job search is to consistently reflect it in all your application materials. Whether you’re blindly soliciting a firm, applying through a jobs board or speaking directly to people you know, you will almost certainly be making an email submission at some point, which means your story should be obvious in all the materials you submit: cover letter, résumé, work samples and so on.

Accomplishing this involves weaving a clear and simple narrative into your cover letter (“My interest in high-level mathematics began with ___ and is present in my work because ___”), supporting it with one or more lines on your résumé (Silver Medalist — 2015 Slam Calculus Competition), then driving the message home with design evidence in your work samples (a building with a serrated form inspired by the Fibonacci sequence). At some point, this tactic will net you an interview, which is an opportunity to tell the story face-to-face in your own words, with an accompanying show-and-tell of your expanded portfolio.

This strategy is no guarantee for employment, but it will certainly help build a recognizable picture of you in the minds of the people who see your application. If you handpick the firms you apply to based on your theme, or customize your theme for the different types of firms you submit materials to, then you’re building a strong case for why you want to work there and why they’d benefit from hiring you — a positive correlation from both angles and maybe also the beginning of a decisive career direction.

Top image via Alex Hogrefe

The post Young Architect Guide: How to Sell Yourself With a Story appeared first on Journal.

Ross Brady via Journal http://bit.ly/2WYfU0s

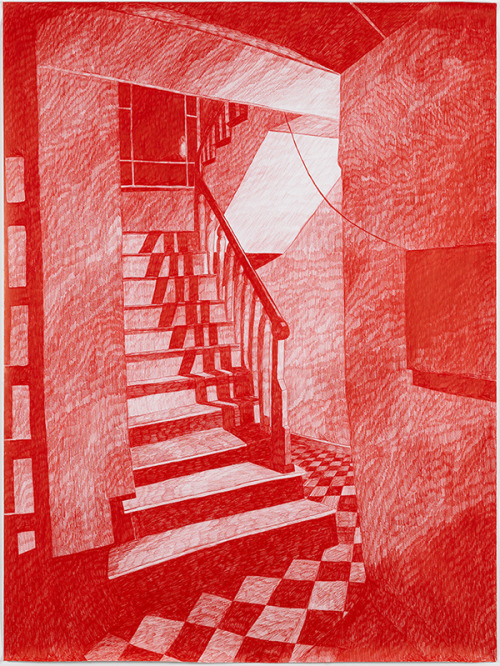

autumn

Octobre

Paris

2018.

.

.

.

xH

(via Golden Mantra Mandala With Red Background)

Shinola Runwell Turntable

Blank William’s Incredible Sculptures

Hispano-Suiza K6, vu par plusieurs carrossiers français - Automobiles Classiques N° 58 octobre / novembre 1993.

Yes, I keep showing you details of 412 14th in Oakland because there are a lot of them. 12/31/2012. I like this one becuase it looks like it is wearing cat ears.

Source IG @mytinyhousetrip

Loving these rustic baskets via @freedom_australia ・・・ Storage goals. Order online and receive free delivery on all of your favourite homewares. Hurry, ends tomorrow! #lovecominghome

Anne-Laure Maison

Pretty Girls & Bourbon