2017

2017

Palavras entre nós Não tenho dinheiro Mas tenho você E eu tenho você Tenho tudo.

More Posts from Ritasakano and Others

<p>Para os meus netos. Quando do término da minha graduação elaborei algumas peças em feltro para auxiliar a alfabetização de crianças. <br> Bem, pensei que usariam com meus futuros alunos. Só pensei, pois não os tive. Quanto aos projetos os acumulei e não parei de cultivar a minha mente e furar os meus dedos.<br> Voltei a eles, com pontos e linhas coloridas. <br> São para os meus netos.

> Livro em feltro Bebê e as formas geométricas. Baseado no livro o Bebê maluquinho de Ziraldo.

The Island Named After a Satellite

It is so small that you cannot see it on Google maps. It measures 25 by 45 meters (27 by 49 yards), about half the size of a football field. This barren bit of rock off the coast of Canada also has an unusual namesake: the Landsat 1 satellite. The small size is actually what made the island notable in 1973, when it was initially discovered. Well, that, and the polar bear trying to eat one of the surveyors.

Betty Fleming, a researcher with the Topographic Survey of Canada, was hunting for uncharted islands and rocks amidst data from the new Landsat 1 satellite. She was particularly interested in the new satellite’s ability to find small features. Working with the Canadian Hydrographic Service, Fleming scanned images of the Labrador coast, an area that was poorly charted. About 20 kilometers (12 miles) offshore, the satellite detected a tiny, rocky island. Surveyors were sent to verify the existence of the island and encountered a hungry polar bear on the island. The surveyor quickly retreated. Eventually, the island became known as “Landsat Island,” after the satellite that discovered it. Watch the video to learn more about Betty Fleming and how Landsat Island was discovered by satellite and ground surveyors.

For more details about Landsat Island, read the full stories here:

The Island Named After a Satellite

The Unsung Woman Who Discovered an Unknown Island

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Sakura uma paixão eterna!!

Cherry Blossoms

Que trabalho maravilhoso!!

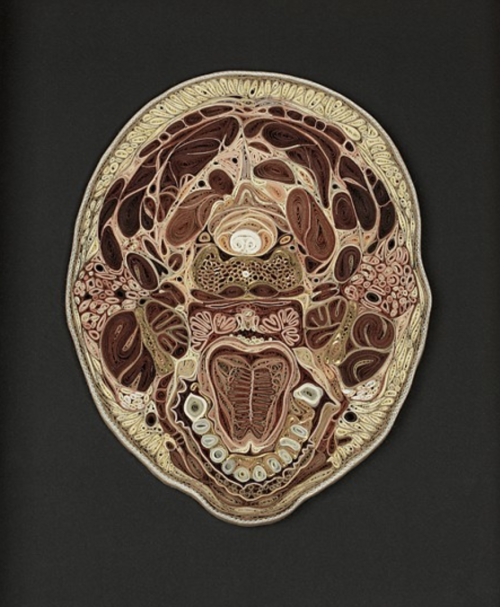

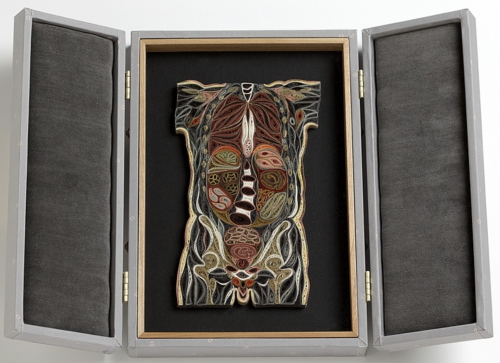

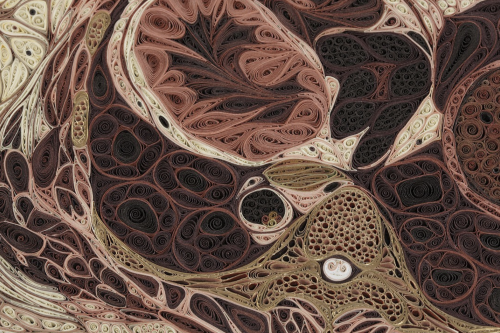

Tissue Series

These pieces are made of Japanese mulberry paper and the gilded edges of old books. They are constructed by a technique of rolling and shaping narrow strips of paper called quilling or paper filigree. Quilling was first practiced by Renaissance nuns and monks who are said to have made artistic use of the gilded edges of worn out bibles, and later by 18th century ladies who made artistic use of lots of free time.

- by Lisa Nilsson

My brother and I saw this precious little rat snake watching everyone gardening in my grandparents’ yard. How could anyone hate this sweet curious face? I was cooing at him for like 20 minutes ♥️

Parabéns!! Que novas descobertas venham!!!

Cassini Mission: What’s Next?

It’s Friday, Sept. 15 and our Cassini mission has officially come to a spectacular end. The final signal from the spacecraft was received here on Earth at 7:55 a.m. EDT after a fateful plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere.

After losing contact with Earth, the spacecraft burned up like a meteor, becoming part of the planet itself.

Although bittersweet, Cassini’s triumphant end is the culmination of a nearly 20-year mission that overflowed with discoveries.

But, what happens now?

Mission Team and Data

Now that the spacecraft is gone, most of the team’s engineers are migrating to other planetary missions, where they will continue to contribute to the work we’re doing to explore our solar system and beyond.

Mission scientists will keep working for the coming years to ensure that we fully understand all of the data acquired during the mission’s Grand Finale. They will carefully calibrate and study all of this data so that it can be entered into the Planetary Data System. From there, it will be accessible to future scientists for years to come.

Even beyond that, the science data will continue to be worked on for decades, possibly more, depending on the research grants that are acquired.

Other team members, some who have spent most of their career working on the Cassini mission, will use this as an opportunity to retire.

Future Missions

In revealing that Enceladus has essentially all the ingredients needed for life, the mission energized a pivot to the exploration of “ocean worlds” that has been sweeping planetary science over the past couple of decades.

Jupiter’s moon Europa has been a prime target for future exploration, and many lessons during Cassini’s mission are being applied in planning our Europa Clipper mission, planned for launch in the 2020s.

The mission will orbit the giant planet, Jupiter, using gravitational assists from large moons to maneuver the spacecraft into repeated close encounters, much as Cassini has used the gravity of Titan to continually shape the spacecraft’s course.

In addition, many engineers and scientists from Cassini are serving on the new Europa Clipper mission and helping to shape its science investigations. For example, several members of the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer team are developing an extremely sensitive, next-generation version of their instrument for flight on Europa Clipper. What Cassini has learned about flying through the plume of material spraying from Enceladus will be invaluable to Europa Clipper, should plume activity be confirmed on Europa.

In the decades following Cassini, scientists hope to return to the Saturn system to follow up on the mission’s many discoveries. Mission concepts under consideration include robotic explorers to drift on the methane seas of Titan and fly through the Enceladus plume to collect and analyze samples for signs of biology.

Atmospheric probes to all four of the outer planets have long been a priority for the science community, and the most recent recommendations from a group of planetary scientists shows interest in sending such a mission to Saturn. By directly sampling Saturn’s upper atmosphere during its last orbits and final plunge, Cassini is laying the groundwork for an potential Saturn atmospheric probe.

A variety of potential mission concepts are discussed in a recently completed study — including orbiters, flybys and probes that would dive into Uranus’ atmosphere to study its composition. Future missions to the ice giants might explore those worlds using an approach similar to Cassini’s mission.

Learn more about the Cassini mission and its Grand Finale HERE.

Follow the mission on Facebook and Twitter for the latest updates.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

O que será que os nossos olhos não enxergam?

NASA’s Fleet of Planet-hunters and World-explorers

Around every star there could be at least one planet, so we’re bound to find one that is rocky, like Earth, and possibly suitable for life. While we’re not quite to the point where we can zoom up and take clear snapshots of the thousands of distant worlds we’ve found outside our solar system, there are ways we can figure out what exoplanets light years away are made of, and if they have signs of basic building blocks for life. Here are a few current and upcoming missions helping us explore new worlds:

Kepler

Launched in 2009, the Kepler space telescope searched for planets by looking for telltale dips in a star’s brightness caused by crossing, or transiting, planets. It has confirmed more than 1,000 planets; of these, fewer than 20 are Earth-size (therefore possibly rocky) and in the habitable zone – the area around a star where liquid water could pool on the surface of an orbiting planet. Astronomers using Kepler data found the first Earth-sized planet orbiting in the habitable zone of its star.

In May 2013, a second pointing wheel on the spacecraft broke, making it not stable enough to continue its original mission. But clever engineers and scientists got to work, and in May 2014, Kepler took on a new job as the K2 mission. K2 continues the search for other worlds but has introduced new opportunities to observe star clusters, young and old stars, active galaxies and supernovae.

Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS)

Revving up for launch around 2017-2018, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will find new planets the same way Kepler does, but right in the stellar backyard of our solar system while covering 400 times the sky area. It plans to monitor 200,000 bright, nearby stars for planets, with a focus on finding Earth and Super-Earth-sized planets.

Once we’ve narrowed down the best targets for follow-up, astronomers can figure out what these planets are made of, and what’s in the atmosphere. One of the ways to look into the atmosphere is through spectroscopy.

As a planet passes between us and its star, a small amount of starlight is absorbed by the gas in the planet’s atmosphere. This leaves telltale chemical “fingerprints” in the star’s light that astronomers can use to discover the chemical composition of the atmosphere, such as methane, carbon dioxide, or water vapor.

James Webb Space Telescope

Launching in 2018, NASA’s most powerful telescope to date, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), will not only be able to search for planets orbiting distant stars, its near-infrared multi-object spectrograph will split infrared light into its different colors- spectrum- providing scientists with information about an physical properties about an exoplanet’s atmosphere, including temperature, mass, and chemical composition.

Hubble Space Telescope

Hubble Space Telescope is better than ever after 25 years of science, and has found evidence for atmospheres bleeding off exoplanets very close to their stars, and even provided thermal maps of exoplanet atmospheres. Hubble holds the record for finding the farthest exoplanets discovered to date, located 26,000 light-years away in the hub of our Milky Way galaxy.

Chandra X-ray Observatory

Chandra X-ray Observatory can detect exoplanets passing in front of their parent stars. X-ray observations can also help give clues on an exoplanet’s atmosphere and magnetic fields. It has observed an exoplanet that made its star act much older than it actually is.

Spitzer Space Telescope

Spitzer Space Telescope has been unveiling hidden cosmic objects with its dust-piercing infrared vision for more than 12 years. It helped pioneer the study of atmospheres and weather on large, gaseous exoplanets. Spitzer can help narrow down the sizes of exoplanets, and recently confirmed the closest known rocky planet to Earth.

SOFIA

The Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) is an airplane mounted with an infrared telescope that can fly above more than 99 percent of Earth’s atmospheric water vapor. Unlike most space observatories, SOFIA can be routinely upgraded and repaired. It can look at planetary-forming systems and has recently observed its first exoplanet transit.

What’s Coming Next?

Analyzing the chemical makeup of Earth-sized, rocky planets with thin atmospheres is a big challenge, since smaller planets are incredibly faint compared to their stars. One solution is to block the light of the planets’ glaring stars so that we can directly see the reflected light of the planets. Telescope instruments called coronagraphs use masks to block the starlight while letting the planet’s light pass through. Another possible tool is a large, flower-shaped structure known as the starshade. This structure would fly in tandem with a space telescope to block the light of a star before it enters the telescope.

All images (except SOFIA) are artist illustrations.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Quando o falar não se faz necessário

Quando o olhar completa as palavras

Quando o toque confessa

Tudo o que somos

Rita Sakano

-

dongwooking liked this · 8 years ago

dongwooking liked this · 8 years ago -

ritasakano reblogged this · 8 years ago

ritasakano reblogged this · 8 years ago