Character Movements (Lips) Part 2

Character Movements (Lips) Part 2

Smiling: The character's lips curl upwards at the corners, indicating happiness, friendliness, or amusement.

Frowning: The character's lips turn downwards, indicating sadness, displeasure, or concern.

Pouting: The character pushes their lower lip forward, often conveying disappointment, sulking, or a desire for attention.

Biting lip: The character lightly bites or presses their lips together, suggesting nervousness, anticipation, or hesitation.

Licking lips: The character's tongue briefly touches or moves across their lips, indicating desire, anticipation, or hunger.

Pressing lips together: The character's lips are firmly pressed together, indicating determination, frustration, or holding back emotions.

Parting lips: The character's lips slightly separate, often indicating surprise, shock, or readiness to speak.

Trembling lips: The character's lips quiver or shake, suggesting fear, anxiety, or suppressed emotions.

Whispering: The character's lips move closer together, and their voice becomes softer, indicating secrecy, confidentiality, or intimacy.

Mouthing words: The character moves their lips without making any sound, often used to convey silent communication or frustration.

More Posts from Writersreferencez and Others

HOW TO WRITE A CHARACTER WHO IS IN PAIN

first thing you might want to consider: is the pain mental or physical?

if it’s physical, what type of pain is it causing? — sharp pain, white-hot pain, acute pain, dull ache, throbbing pain, chronic pain, neuropathic pain (typically caused by nerve damage), etc

if it’s mental, what is the reason your character is in pain? — grief, heartbreak, betrayal, anger, hopelessness, fear and anxiety, etc

because your character will react differently to different types of pain

PHYSICAL PAIN

sharp and white-hot pain may cause a character to grit their teeth, scream, moan, twist their body. their skin may appear pale, eyes red-rimmed and sunken with layers of sweat covering their forehead. they may have tears in their eyes (and the tears may feel hot), but they don’t necessarily have to always be crying.

acute pain may be similar to sharp and white-hot pain; acute pain is sudden and urgent and often comes without a warning, so your character may experience a hitched breathing where they suddenly stop what they’re doing and clench their hand at the spot where it hurts with widened eyes and open mouth (like they’re gasping for air).

dull ache and throbbing pain can result in your character wanting to lay down and close their eyes. if it’s a headache, they may ask for the lights to be turned off and they may be less responsive, in the sense that they’d rather not engage in any activity or conversation and they’d rather be left alone. they may make a soft whimper from their throat from time to time, depends on their personality (if they don’t mind others seeing their discomfort, they may whimper. but if your character doesn’t like anyone seeing them in a not-so-strong state, chances are they won’t make any sound, they might even pretend like they’re fine by continuing with their normal routine, and they may or may not end up throwing up or fainting).

if your character experience chronic pain, their pain will not go away (unlike any other illnesses or injuries where the pain stops after the person is healed) so they can feel all these types of sharp pain shooting through their body. there can also be soreness and stiffness around some specific spots, and it will affect their life. so your character will be lucky if they have caretakers in their life. but are they stubborn? do they accept help from others or do they like to pretend like they’re fine in front of everybody until their body can’t take it anymore and so they can no longer pretend?

neuropathic pain or nerve pain will have your character feeling these senses of burning, shooting and stabbing sensation, and the pain can come very suddenly and without any warning — think of it as an electric shock that causes through your character’s body all of a sudden. your character may yelp or gasp in shock, how they react may vary depends on the severity of the pain and how long it lasts.

EMOTIONAL PAIN

grief can make your character shut themself off from their friends and the world in general. or they can also lash out at anyone who tries to comfort them. (five states of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and eventual acceptance.)

heartbreak — your character might want to lock themself in a room, anywhere where they are unseen. or they may want to pretend that everything’s fine, that they’re not hurt. until they break down.

betrayal can leave a character with confusion, the feelings of ‘what went wrong?’, so it’s understandable if your character blames themself at first, that maybe it’s their fault because they’ve somehow done something wrong somewhere that caused the other character to betray them. what comes after confusion may be anger. your character can be angry at the person who betrayed them and at themself, after they think they’ve done something wrong that resulted in them being betrayed, they may also be angry at themself next for ‘falling’ for the lies and for ‘being fooled’. so yes, betrayal can leave your character with the hatred that’s directed towards the character who betrayed them and themself. whether or not your character can ‘move on and forgive’ is up to you.

there are several ways a character can react to anger; they can simply lash out, break things, scream and yell, or they can also go complete silent. no shouting, no thrashing the place. they can sit alone in silence and they may cry. anger does make people cry. it mostly won’t be anything like ‘ugly sobbing’ but your character’s eyes can be bloodshot, red-rimmed and there will be tears, only that there won’t be any sobbing in most cases.

hopelessness can be a very valid reason for it, if you want your character to do something reckless or stupid. most people will do anything if they’re desperate enough. so if you want your character to run into a burning building, jump in front of a bullet, or confess their love to their archenemy in front of all their friends, hopelessness is always a valid reason. there’s no ‘out of character’ if they are hopeless and are desperate enough.

fear and anxiety. your character may be trembling, their hands may be shaky. they may lose their appetite. they may be sweaty and/or bouncing their feet. they may have a panic attack if it’s severe enough.

and I think that’s it for now! feel free to add anything I may have forgotten to mention here!

Showing 'Anticipation' in Writing

Fingers tapping rhythmically on a surface.

Shifting weight from one foot to the other.

Checking the time frequently.

Eyes darting to the door or window expectantly.

Taking deep, excited breaths.

Biting the lower lip in nervous excitement.

Rubbing hands together eagerly.

Whispering, “I can’t wait” to themselves or others.

Fidgeting with objects, like twisting a ring or playing with a pen.

Heart pounding with eagerness.

Perking up at any noise that might signal the anticipated event.

Smiling slightly, as if imagining the future moment.

Knees bouncing up and down while seated.

Glancing at their phone or watch repeatedly.

Clutching a piece of clothing or accessory tightly.

Standing on tiptoe to get a better view.

Ears straining to catch any sound.

Swallowing nervously, throat dry with excitement.

Humming or softly singing to pass the time.

Practicing a speech or action they are looking forward to.

If you write a strong character, let them fail.

If you write a selfless hero, let them get mad at people.

If you write a cold-heated villain, let them cry.

If you write a brokenhearted victim, let them smile again.

If you write a bold leader, let them seek guidance.

If you write a confident genius, let them be wrong, or get stumped once in a while.

If you write a fighter or a warrior, let them lose a battle, but let them win the war.

If you write a character who loses everything, let them find something.

If you write a reluctant hero, give them a reason to join the fight.

If you write a gentle-hearted character who never stops smiling, let that smile fade and tears fall in shadows.

If you write a no one, make them a someone.

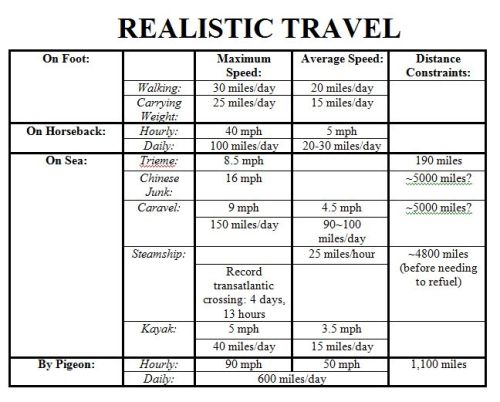

If you write a sibling, let them fight and bicker, but know that at the end of the day they’ll always have each other’s back.

If you write a character, make them more than just a character; give them depth, give them flaws and secrets, and give them life.

For any writers: http://er.jsc.nasa.gov/seh/SFTerms.html

For more facts, follow Ultrafacts

So you know when you're writing a scene where the hero is carrying an injured person and you realize you've never been in this situation and have no idea how accurate the method of transportation actually is?

Oh boy, do I have a valuable resource for you!

Here is a PDF of the best ways to carry people depending on the situation and how conscious the injured person needs to be for the carrying position.

Literally a life saver.

(No pun intended.)

Body Language Cheat Sheet For Writers

╰ Facial expressions

These are your micro-signals, like the blinking neon signs of the soul. But they’re small, quick, and often lie harder than words.

Raised eyebrows — This can mean surprise or disbelief, sure. But it can also be a full-on, silent “Are you serious right now?” when someone’s being ridiculous. Or even curiosity when someone’s too emotionally repressed to askthe damn question.

Furrowed brow — That face people make when they’re doing long division in their head or trying to emotionally process a compliment. It’s thinking, yes—but also confusion, deep frustration, or quiet simmering rage.

Smiling — Can be happiness… or total fake-it-till-you-make-it energy. Some smiles are stiff. Some don’t reach the eyes. Show that.

Frowning — Sure, sadness. But also: disappointment, judgment, or the universal “I’m about to say something blunt, brace yourself.”

Lip biting — It’s not just nervousness, it’s pressure. Self-control. Anticipation. It’s the thing people do when they want to say something and decide, at the last second, not to.

╰ Eye movement

The window to the soul? Yeah. But also the window to when someone’s lying, flirting, or deeply trying not to cry in public.

Eye contact — Confidence or challenge. Eye contact can be gentle, curious, sharp like a blade. Sometimes it’s desperate: “Please understand me.”

Avoiding eye contact — Not always guilt. Sometimes it’s protectiveness. Sometimes it’s “I’m afraid if I look at you, you’ll see everything I’m trying to hide.”

Narrowed eyes — Calculating. Suspicious. The look someone gives when their brain’s saying “hmmm...” and it’s not a good hmm.

Wide eyes — Surprise, yes. But also sudden fear. The oh-God-it’s-happening look. Or when someone just found out they’re not as in control as they thought.

Eye roll — Classic. But try using it with tension, like when someone’s annoyed and trying very hard not to lose it in public.

╰ Gestures

This is where characters’ emotions go when their mouths are lying.

Crossing arms — Not just defensive. Sometimes it’s comfort. A self-hug. A barrier when the conversation is getting too personal.

Fidgeting — This is nervous energy with nowhere to go. Watch fingers tapping, rings spinning, sleeves tugged. It says: I’m not okay, but I’m trying not to show it.

Pointing — It’s a stab in the air. Aggressive, usually. But sometimes a desperate plea: Look. Understand this.

Open palms — Vulnerability. Honesty. Or a gesture that says, “I have nothing left to hide.”

Hand on chin — Not just thinking. It’s stalling. It’s delaying. It’s “I’m about to say something that might get me in trouble.”

╰ Posture and movement

These are your vibes. How someone occupies space says everything.

Slumped shoulders — Exhaustion. Defeat. Or someone trying to take up less space because they feel small.

Upright posture — Not always confidence. Sometimes it’s forced. Sometimes it’s a character trying really, really hard to look like they’re fine.

Pacing — Inner chaos externalized. Thinking so loudly it needs movement. Waiting for something. Running from your own thoughts.

Tapping foot — Tension. Irritation. Sometimes a buildup to an explosion.

Leaning in — Intimacy. Interest. Or subtle manipulation. (You matter to me. I’m listening. Let’s get closer.)

╰ Touch

This is intimacy in all its forms, comforting, protective, romantic, or invasive.

Hugging — Doesn’t always mean closeness. Could be a goodbye. Could be an apology they can’t say out loud. Could be awkward as hell.

Handshake — Stiff or crushing or slippery. How someone shakes hands says more than their words do.

Back patting — Casual warmth. Bro culture. Awkward emotional support when someone doesn’t know how to comfort but wants to try.

Clenched fists — Holding something in. Rage, tears, restraint. Fists mean tension that needs somewhere to go.

Hair tuck — Sure, flirtation or nerves. But also a subtle shield. A way to hide. A habit from childhood when someone didn’t want to be seen.

╰ Mirroring:

If two characters start syncing their body language, something is happening. Empathy. Chemistry. Shared grief. If someone shifts their body when the other does? Take notice. Other human bits that say everything without words...

Nodding — Not just yes. Could be an “I hear you,” even if they don’t agree. Could be the “keep going” nod. Could be patronizing if done too slow.

Crossed legs — Chill. Casual. Or closed-off, depending on context. Especially if their arms are crossed too.

Finger tapping — Time is ticking. Brain is pacing. Something’s coming.

Hand to chest — Sincerity, yes. But also shock. Or grounding—a subconscious attempt to stay present when everything feels like too much.

Tilting the head — Curiosity. Playfulness. Or someone listening so hard they forget to hide it.

Temple rub — “I can’t deal.” Could be physical pain. Could be stress. Could be emotional overload in disguise.

Chin stroking — Your classic “I’m judging you politely.” Often used in arguments between characters pretending to be calm.

Hands behind the back — Authority. Control. Or rigid fear masked as control.

Leaning body — This is the body betraying the brain. A tilt toward someone means they care—even if their words are cold.

Nail biting — Classic anxiety. But also habit. Something learned. Sometimes people bite because that’s how they self-soothe.

Squinting — Focusing. Doubting. Suspicion without confrontation.

Shifting weight — Uncomfortable. Unsure. Someone who wants to leave but doesn’t.

Covering the mouth — Guilt. Hesitation. The “should I say this?” moment before something big drops.

Body language is more honest than dialogue. If you really want to show your character’s internal world, don’t just give them lines. Give them a hand that won’t stop shaking. Give them a foot that won’t stop bouncing. Give them a mouth that smiles when their eyes don’t. And if you’re not sure what your character would do in a moment of fear, or love, or heartbreak, try acting it out yourself. Seriously. Get weird. Feel what your body does. Then write that down.

PLEASE, PLEASE STOP SCROLLING.

BOOST, BOOST, BOOST! Especially if you don’t live in the U.S., because that’s all you can do to help us.

If you DO live here, this post has 5 things you can do; feel free to skip to the bullet points.

I’m sure you’re sick of seeing this, but we are in the final stages of the Net Neutrality repeal. I know long posts about this can be overwhelming, so at least just pick a bullet point and do it! HOPE IS NOT LOST YET.

WE STILL HAVE ONE LAST CHANCE — Until April 27th

There’s a CRA (Congressional Review Act) vote to get Net Neutrality back, and it may still win. THIS IS BECAUSE OF US!!! Enough people in congress listened to our calls, emails, and tweets, so a CRA has been called for to try and stop Ajit Pai.

Long posts about this can be overwhelming, so I’ll keep it simple and just list some quick and easy options below for how you can help save it. WE’VE ALREADY MADE PROGRESS, KEEP GOING! WE’RE SO CLOSE! I’m lucky enough to have the ability to do these, so I’m doing all of them, even though it’s hard for me. Do it for the people who can’t. Do it for those who will LOSE THEIR JOBS or their educations or their friends or their support. Do it for the kids too young to use a phone. Do it for the families who might be put out of homes. Do it for everyone.

WE NEED ONE MORE SENATE VOTE. DO AT LEAST ONE OF THESE 5 THINGS IF YOU’RE PHYSICALLY CAPABLE

[Info and Resources for Action]

FIRST OFF, if you don’t know what to say, here are some basic templates as well as my own that have had an effect in the past.

For your Senator’s contact info (phone/email/twitter/etc): http://act.commoncause.org/site/PageServer?pagename=sunlight_advocacy_list_page

[Action to Take]

KEY: bold = most important, *** = quickest/easiest to do

Here you can write anything and they’ll email it around: https://www.battleforthenet.com/

*** OR just scroll down and click a Senator to tweet them.

*** Just type your zip code here, and it’ll email/tweet your Senators! https://www.publicknowledge.org/act-now/tell-congress-to-use-the-cra-to-save-net-neutrality/#anchor

Text RESIST to 50409 (reply Senate, then copy any of the templates or write your own) — it’ll automatically email/fax it

*** Reblog, Retweet, and tell people as much as possible! But that alone isn’t enough. Get your friends/family/classmates to do these, too!!!

If you can do this last one, if you’re at all able, do it.

Call the Capitol at 202-224-3121. Just say where you’re from and they’ll transfer you to your senator’s office. Here’s a template for what to say:

“Hello, I’m [name], and I’m a constituent of Senator [name]. I’m calling to urge them to vote in support of net neutrality, as it is very important to the general public. I am watching their actions on net neutrality, and it will influence my vote in coming years. Thank you!”

(This also works as a great template for tweets/emails to your Senators)

Side Note: You can go here to see how many calls each of your Sen/Reps have already received: https://www.battleforthenet.com/scoreboard/ – it’s cool to see that a lot of calls CAN AND HAVE change(d) the vote!

THIS IS 2018 — WE CAN VOTE THEM OUT THIS YEAR AND THEY KNOW IT. USE THAT LEVERAGE.

On Scars

(This post is an excerpt from Maim Your Characters: How Injuries Work in Fiction.)

First off, let me be clear about what I mean when I say the word scars. I’m not talking about the medical definition: rough tissue that overlies a wound as it heals over time.

I’m using a broader definition of any physical evidence of a previous injury.

That can be the amputated hand, the limp from a spinal cord injury.

It can also include tattoos. (Maui’s moving tattoos in Moana are a perfect example of this: his tattoos are a physical embodiment of where he’s been.)

Scars, by this broad definition, are an interesting shorthand for a story, whether we actually see that tale or not. We use them as a way to say there’s a story here. Sometimes our global story gives us the chance to tell it, sometimes not; either way, scars can be an interesting way to add depth to a character.

In fact, sometimes a scar is integral to explaining and understanding who that character is.

For example, we know that Peter Pan’s Captain Hook has been involved in some fierce battles, because he lost his hand – and had it replaced with his legendary pirate hook. That hook is a symbol of the cold cruelty he now gives off.

The eponymous Harry Potter wouldn’t truly be Harry without his lightning-bolt forehead scar. For Harry, it’s not just about his past, it’s about his future: his fate and the fate of the scar-giver are intertwined, a battle that will determine the fate of the world. Worse, it’s all inscribed on his forehead, for everyone to see.

Darth Vader’s scars in Star Wars are extensive, so much so that they shroud his identity completely. While we see the faces of the heroes, and even of Emperor Palpatine himself, Vader’s wounds require a respirator mask that obscures his face and makes him the terrifying villain he is. He’s actually turned the support system he needs to stay alive – a depersonalizing suit and respirator – into something useful, a mask to terrify his enemies. Vader’s life is, in some ways, enhanced by his disability, and he’s certainly comfortable moving in his world with the scars he’s got.

In Moana, the demigod Maui’s scars are branded on him as tattoos. These are the stories of who he’s been and where he goes. When hero-protagonist Moana asks him where they come from, he tells her, “They show up when I earn them.”

This isn’t dissimilar to the battle scars on an old soldier, sailor, or mercenary: their wounds are manifested on their flesh.

But if scars are shorthand for a story, if they’re someone’s past writ large, we need to honor that character in the way we represent them. If we elect to give a character scars, they should represent not a plot but a story, something that not only wounds the character but drives them to change internally.

As an example, I’m going to tell you the story of two of my personal scars. At the end we’ll discuss which one would go into a story about me, and why.

Scar #1: The Knife Point. When I was six or seven, I was trying to get some corn off the cob — I wanted to eat it in kernel form for some reason, and I was using a kitchen knife. I got the corn off all right — and drove the point of the knife straight into the webbing between my thumb and forefinger on my left hand. Ouch!

(Actually, it didn’t hurt, it was the sheer volume of blood that was terrifying).

I changed in that I learned not to do that specific task (cutting corn off the cob) that specific way (driving the knife toward my hand).

But it’s not a marker of who I am.

Scar #2: The Bite Mark. Let’s consider another scar, also on my left hand. There’s an old bite mark by the heel of my hand, at the base of my left thumb.

It happened like this: I was fifteen or so, and my neighbor’s dog, Clancy, wasn’t doing well. He was old and he was sick. That day he had become too sick to get up. It was time for my neighbor to take him to the vet and say goodbye.

She had him on a blanket. But he was a big dog, and the vet was far, and she didn’t have a car, and so our neighbor came to ask me and my mom to help get him to the vet. Of course we said yes. We liked her, but more importantly, we loved animals. (Both my mother and I had worked at the vet at one point or another.)

When we went to move him by picking up the blanket and moving him to the car, Clancy reached out and bit me. Not because he was a bad dog, not because he was out to hurt me. He bit me because he was scared and sick and hurt and he didn’t know what to do.

I didn’t feel anger at Clancy, and I didn’t turn afraid of him. I felt sympathy. His act hurt my skin. His pain broke my heart.

So when we got him to the vet, while they were easing his pain and saying goodbye, I calmly and quietly washed my wound in the sink with an antiseptic.

I learned something about myself in that moment.

I learned that healing really is a calling for me. That I was glad we had cared for him and that I was able to help him on his final journey. I was glad to know Clancy. I wasn’t mad, or hurt, even though my hand stung from the antiseptic.

That scar helped me find my internal true north.

Now, which of those scars has meaning? Which of them would you want to include if you were writing me as a character? Which do you think would make it into a memoir, if I wrote one? It’s most certainly the second, the one that helped me figure out who I am, the one that drove me to learn about myself. The first is something that happened; the second is something that changed me.

It’s stories like these that you should use in order to figure out who your characters are – and how to honor them.

Let’s Talk Tattoos.

Tattoos are interesting in that they can be another, more interesting set of shorthand. Unless your character has a Maui-like situation going on, her tattoos won’t simply appear. She’ll not only have to choose what story she wants to represent on her flesh, but she’ll have to choose how to express that story in an image. Then comes the pain of the ritual scarification: the injection of ink under the skin, a microbaptism in pain and blood and pigment.

Tattoos are absolutely fascinating. Because they don’t typically connect to physical wounds so much as to emotional ones, they’re a really great piece of shorthand for getting into the depths of who someone truly is.

My own tattoos are direct messages to myself about how I should live in the world. They’re an easily visible piece of guidance that explores what my role is and should be in the world.

Of course, not all tattoos have this deeper meaning. People choose to tattoo things on themselves for a hundred different reasons, the aesthetics of the design being one of them. Some tattoos are simply trendy. I’m not here to judge anyone’s ink!

But if you’re going to cover a character in tattoos, consider having each of them explore a deeper facet of that character’s personality and the journey they’ve been on.

How to Use Scars Effectively

As we said above, scars are a shorthand for a story. Prominent scars, particular facial or obvious hand scars, are a constant source of tension and questions. When someone has a big scar on their face, we find our eyes drawn to it, a question forming on our tongue: What happened?

But the What happened? isn’t as important as How did it change you? And so my general recommendation with scars is twofold and contradictory:

One: only introduce scars if it’s an incredibly important part of a character’s past.

Two: only introduce scars if it’s an incredibly important part of a character’s future.

So why the two recommendations? Why the contradiction?

Characters are constantly moving, if not in space, then through time. Their scars shape their past, which shapes where they are now and where they’re going.

If a scar is germane to a character’s past, it helps establish where they’re coming from and what their experiences have been.

But those experiences are only important if that scar-causing event is relevant to their future.

The scar a sea captain got fending off pirates once upon a time doesn’t have much to add if his current quest is finding new plumbing for his house. His scar isn’t relevant, unless it intimidates the shady plumber into giving him a better price. Even then, it’s a shallow connection.

Consider the old injury (and its scar) to be a cause.

Ask: what was the effect? If your character got a scar on their eyebrow from a bike accident when she was seven, that scar doesn’t mean anything… unless that was the bike accident where she failed to protect and save her kid brother, which makes her overprotective and hypercautious now.

If she crashed her bike as a kid and merely went on with her life… what was the point? Why tell that story with a scar so visible?

Remember that the point of a story is that people change. If a scar doesn’t fundamentally shape a character, consider simply leaving it out. Window dressing is just that: window dressing.

What we want is to give more insight into who your character is.

Avoiding Wandering Scar Syndrome

Wandering Scar Syndrome is when a character’s scar is on their left eye on Page 3 and their right cheek on Page 12. It’s simply a symptom of not taking good notes.

There are two techniques I’m going to suggest here.

The first is, keep character sheets. Many writers choose to do this, many do not. But especially if you’re going to wallpaper your character with scars and tattoos, it’s worth writing down where they are and what they look like. In fact, copy/pasting the way they were originally described into a separate document is particularly helpful in being sure your descriptions stay consistent throughout the story. It’s a pain in the butt for a moment, but it helps so much with consistency down the line!

Another option is to use [brackets] as an aside.

What do I mean?

Let’s say you talk about a minor character in two different places in the story, chapters — even acts apart.

Kitty Scarborough was the best fighter in town, and she bore the scars to prove it. [Kitty Scar Description — line on her face?] Or, [scar TK]

TK is the editor’s mark for To Come, a placeholder of sorts, and it’s useful for all kinds of things: Name TK, Dog Breed TK, Red sports car [make/model TK], etc. (Once upon a time, this book was littered with TKs .)

Later, we can pull it back up: A tall redhead walked through the door. Kitty Scarborough was easy to recognize, especially by her [Kitty Scar Description].

Why does this work? Why is this helpful?

Because it allows us to maintain flow as a writer. If we know Kitty’s got scars from fighting, we can come up with what exactly those look like later. (We’re using them as evidence of her toughness and battle prowess, not for a particular meaning behind each individual scar she’s got.) So when we describe Kitty, we don’t need to spend ten minutes racking our brain for a cool scar to give her — we can do that later. All we need to drop into our first draft is [Kitty scar] and we can move on!

This works for all sorts of details, from car models to hair colors to background characters’ names, so don’t think it’s just a scar locater!

Later on we can come back, look through our manuscript with the magical Find tool, and simply search for that left bracket, [ . Anything that comes up can be filled in with your text!

Want a good scar generator, including ideas for how it shaped the character? Visit MaimYourCharacters.com/Scars !

This post is an excerpt from Maim Your Characters, from Even Keel Press. If you’d like to read a 100-page sample of the book, [click here]. If you’d like to order a print copy, it’s available [via Amazon.com], and digital copies are available from [a slew of retailers].

xoxo, Aunt Scripty

Make your deaths mean something

I was beta reading a book for a friend from the NaNo group where I live and during a certain part of the book, I sensed that someone in the story was going to die. I’d never read anything by her, so I wasn’t sure what to expect from the immanent death and it made me a bit nervous. (I even messaged her on Facebook to tell her that I would be disappointed if she “Romeo and Juliette-ed” the story.

After finishing the story, I thought it would be a good idea to write a bit about using death in your stories. What kinds of pitfalls you might encounter and how it can help your story grow.

Fiction vs Reality

Death is a fact of life. I’m sure you’ve heard this quote from Ben Franklin: “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.”

It has become a bit cliche, but that doesn’t change the truth in the quote. If you ignore the revolving door of certain fictional characters, everyone is going to die.

In fiction, death is less permanent. Harry Potter (and Voldemort for that matter) died at some point in the novels. Jean Grey and death are old friends that visit from time to time. (Although Magneto has been dead more times.)

So what does this mean for your story? Here are a few suggestions:

Death has an impact on your story and the characters in your story. Do not treat a death lightly.

How will your characters grow because of this death?

How will it change the message of your story?

Ask yourself why, in the structure of your story, the character has to die.

Let’s consider a popular fictional death-Gandalf the Grey.

Gandalf is the leader of the company because of his knowledge Middle Earth. He has long wandered the highways and byways of the world and knows many of the secret places. When he leads the company to the mines of Moira, it is because the path is secret and will hide them from prying eyes.

The problem the story encounters is that Gandalf has become a crutch to the story. If he remains, then every problem can and will be solved by him. No one will grow, and the story will stagnate.

Gandalf’s death brings about many changes. Here are a few of them:

Boromir has a motive to lose faith in the company’s ability to bring the ring to Mordor.

Aragorn has to take charge of the company.

Frodo realizes that he is endangering the rest of the company.

Gandalf’s death is the catalyst for all of the action that takes place afterwards.

What purpose does death serve in a story?

Gandalf is just one example of a death in a story, and death can serve many purposes in a narrative.Let’s consider some of the ways that death can have an impact on your narrative:

Bring change to your living characters-Sometimes your characters need something to motivate them to change their lives. Death can be such a factor. Perhaps your character will decide the death is a reason to change their habits or lifestyle.

Create an emotional impact-Most of your readers will have experienced death in their lives, and these experiences cause some sort of emotional response.

Make the story longer by making it harder to accomplish the goal-What if the death is of a key character for the goal your characters are trying to accomplish? That can add to your word count as they strive to overcome this sudden lack.

Create an atmosphere-Especially if you are working in a genre such as horror, incorporating death in the story can create or enhance an aura of dread to your tale.

Accelerate the pace of the story-Death can make the elements of your story move more quickly, especially if the characters that are still alive feel a sense of immediacy.

Cause change for the sake of change- This is seen quite often during National Novel Writing Month in the form of the Traveling Shovel of Death. Killing off a character can bring about a wide variety of new dynamics in your story, but I wouldn’t recommend using it just because you don’t know what else to do.

Because art reflects life, and sometimes people die in real life- We already mentioned that death is a part of life, and sometimes death just happens, but make sure you understand how it will impact your story before you jump into it.

In order to un-kill them later/have a surprise return-This one is easy to abuse. Sure it can add to your story, but don’t do it too much.

Fulfilling revenge/just desserts- Sometimes your story just needs some payback, so why not let your character just go for it?

Demonstrate the severity of a situation- Think about every ‘bad guy’ scene in a movie. What does the bad guy do to prove just how bad he is? He shoots somebody. It may not always be fatal, but it proves a point.

Make a plan fail- Think back to Gandalf. His death upset the plan for the company to travel to Mount Doom together. This makes the story change direction.

Avoid cliches

Let’s take a moment to talk about cliches. Cliches are everywhere, and there are more of them every day. So how did cliches get to be so cliche in the first place?

A cliche is kind of like peer pressure-Everybody’s doing it. That’s how it became a cliche. In fact, every cliche was once an original idea, and everybody loved it. Just think, there was once a movie audience that had never seen any of the horror cliches, and they were amazed and shocked by the jump scares, and other overdone tricks that we groan about.

The problem with originality is that after someone sees it and wants to use it for their own project, there’s the danger of everyone wants to try it too. Before long, that unique take on the world has become overdone and boring.

What’s worse is that people are going to forget who had the original idea. If you look at the Lord of the Rings, it’s just like so much of the fantasy stories out there these days, but don’t forget that Tolkein wrote his books when the world of fantasy was young.

So what does that have to do with death in your story anyway?

Common Death Cliches

Coming back from the dead- This is a huge thing in comic books, but that is a different kind of medium and comic book companies depend on those big name characters to draw in readers, but that isn’t your book. Your story needs a sense of permanence. So when death happens, only take it back if it serves a purpose in the story.

I’m Not Dead Yet- We see this in every horror movie. the monster isn’t really dead yet. The fine fellows from Monty Python made a great scene where they spoofed this idea with the Black Knight. Even after he was only standing on one leg with no arms, he was still hopping around trying to kill Arthur.

Killing a character because you don’t know what else to do- Sure you need to introduce some change into your story, but death isn’t always the answer.

Getting rid of a character that doesn’t fit into your story- Better ways to get rid of that character include, but are not limited to: moving, getting lost, being kidnapped, alien abducted, you get the idea.

Hopefully that gives you some food for thought about death. (Yes, I am well aware that ‘food for thought’ is a cliche, but I wanted to check if you were paying attention.)

If you have other questions, let us know, and feel free to give us some feedback on the post.

Billy

Here’s an invaluable writing resource for you.

-

rihananextdoor liked this · 1 week ago

rihananextdoor liked this · 1 week ago -

nikola11ismine liked this · 1 week ago

nikola11ismine liked this · 1 week ago -

saintsroww liked this · 1 week ago

saintsroww liked this · 1 week ago -

marielaure liked this · 2 weeks ago

marielaure liked this · 2 weeks ago -

ghostsandgod liked this · 2 weeks ago

ghostsandgod liked this · 2 weeks ago -

a-little-harmed-shinra liked this · 2 weeks ago

a-little-harmed-shinra liked this · 2 weeks ago -

thecreatorstar17 liked this · 2 weeks ago

thecreatorstar17 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

mnemosyne-101 liked this · 3 weeks ago

mnemosyne-101 liked this · 3 weeks ago -

writesick-lover liked this · 3 weeks ago

writesick-lover liked this · 3 weeks ago -

cielbloodrain liked this · 3 weeks ago

cielbloodrain liked this · 3 weeks ago -

pokedex-holder-pink reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

pokedex-holder-pink reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

iwritingsblog reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

iwritingsblog reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

iknowaristotle liked this · 3 weeks ago

iknowaristotle liked this · 3 weeks ago -

shewasafairyyop liked this · 3 weeks ago

shewasafairyyop liked this · 3 weeks ago -

yesthefandomfreakblr liked this · 3 weeks ago

yesthefandomfreakblr liked this · 3 weeks ago -

diamadozen reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

diamadozen reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

spookypatrolscissorslover liked this · 3 weeks ago

spookypatrolscissorslover liked this · 3 weeks ago -

thetranstwink liked this · 1 month ago

thetranstwink liked this · 1 month ago -

malerd liked this · 1 month ago

malerd liked this · 1 month ago -

thehomiewhowrites reblogged this · 1 month ago

thehomiewhowrites reblogged this · 1 month ago -

askamirathefatesealer liked this · 1 month ago

askamirathefatesealer liked this · 1 month ago -

jellybean54211 liked this · 1 month ago

jellybean54211 liked this · 1 month ago -

ferje-flamsburg reblogged this · 1 month ago

ferje-flamsburg reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ferje-flamsburg liked this · 1 month ago

ferje-flamsburg liked this · 1 month ago -

blackspies12 reblogged this · 1 month ago

blackspies12 reblogged this · 1 month ago -

blackspies12 liked this · 1 month ago

blackspies12 liked this · 1 month ago -

mieuxn liked this · 1 month ago

mieuxn liked this · 1 month ago -

pokespefangirl reblogged this · 1 month ago

pokespefangirl reblogged this · 1 month ago -

pokespefangirl liked this · 1 month ago

pokespefangirl liked this · 1 month ago -

bastardsaint liked this · 1 month ago

bastardsaint liked this · 1 month ago -

miasarah liked this · 1 month ago

miasarah liked this · 1 month ago -

kisses-for-you liked this · 1 month ago

kisses-for-you liked this · 1 month ago -

vesclaine liked this · 1 month ago

vesclaine liked this · 1 month ago -

unpersoniverse liked this · 1 month ago

unpersoniverse liked this · 1 month ago -

kmoftherose reblogged this · 1 month ago

kmoftherose reblogged this · 1 month ago -

kmoftherose liked this · 1 month ago

kmoftherose liked this · 1 month ago -

2828hi liked this · 1 month ago

2828hi liked this · 1 month ago -

m0nkienerd liked this · 1 month ago

m0nkienerd liked this · 1 month ago -

ohdabi-kun liked this · 1 month ago

ohdabi-kun liked this · 1 month ago -

amaranthine-undying reblogged this · 1 month ago

amaranthine-undying reblogged this · 1 month ago -

amaranthine-undying liked this · 1 month ago

amaranthine-undying liked this · 1 month ago -

cigvrrcte reblogged this · 1 month ago

cigvrrcte reblogged this · 1 month ago -

charlie-mac-posts liked this · 1 month ago

charlie-mac-posts liked this · 1 month ago -

red-dead-obsession liked this · 1 month ago

red-dead-obsession liked this · 1 month ago -

vantasariae liked this · 1 month ago

vantasariae liked this · 1 month ago -

copperboom82 liked this · 1 month ago

copperboom82 liked this · 1 month ago -

canis-2bs liked this · 1 month ago

canis-2bs liked this · 1 month ago