Failed Prank

Failed Prank

More Posts from Ourvioletdeath and Others

Who would like to undulate in the darkness with me

STOP SCROLLING!

Please read this if you want to make a sick boy happy. Lorenzo Snippe is a 9-year-old boy from the Netherlands who is very sick. In 2016 he was diagnosed with leukemia and in 2017 with x-ald. On the third (3) of February is his tenth (10) birthday, and it will probably be his last. Because he can’t get any visitors due to being so sick, his parents have asked people in this news article to send him a happy birthday postcard as soon as possible.

If you’re able to, please send him a postcard wishing him a happy birthday and tell him where you’re from! If you can’t, please reblog this post to make sure it will reach as many people as possible! His address is:

Prinses Wilhelminastraat 22

7753 TM Dalerpeel

The Netherlands

He really loves animals, so it would be great if you could send a postcard with an animal on it or something like that!

Don’t send him or his family rude things and don’t use his address for other things than described in this post!

😂😂

I love the quotation marks.

Is Your Nervous System a Democracy or a Dictatorship?

A single “dictator neuron” can take charge of complex behaviors

How does the architecture of our brain and neurons allow each of us to make individual behavioral choices? Scientists have long used the metaphor of government to explain how they think nervous systems are organized for decision-making. Are we at root a democracy, like the U.K. citizenry voting for Brexit? A dictatorship, like the North Korean leader ordering a missile launch? A set of factions competing for control, like those within the Turkish military? Or something else?

In 1890, psychologist William James argued that in each of us “[t]here is… one central or pontifical [nerve cell] to which our consciousness is attached.” But in 1941, physiologist and Nobel laureate Sir Charles Sherrington argued against the idea of a single pontifical cell in charge, suggesting rather that the nervous system is “a million-fold democracy whose each unit is a cell.”

So who was right?

For ethical reasons, we’re rarely justified in monitoring single cells in healthy people’s brains. But it is feasible to reveal the brain’s cellular mechanisms in many nonhuman animals. As I recount in my book “Governing Behavior,” experiments have revealed a range of decision-making architectures in nervous systems – from dictatorship, to oligarchy, to democracy.

A Neural Dictatorship

For some behaviors, a single nerve cell does act as a dictator, triggering an entire set of movements via the electrical signals it uses to send messages. (We neurobiologists call those signals action potentials, or spikes.) Take the example of touching a crayfish on its tail; a single spike in the lateral giant neuron elicits a fast tail-flip that vaults the animal upward, out of potential danger. These movements begin within about one hundredth of a second of the touch.

Similarly, a single spike in the giant Mauthner neuron in the brain of a fish elicits an escape movement that quickly turns the fish away from a threat so it can swim to safety. (This is the only confirmed “command neuron” in a vertebrate.)

Each of these dictator neurons is unusually large – especially its axon, the long, narrow part of the cell that transmits spikes over long distances. Each dictator neuron sits at the top of a hierarchy, integrating signals from many sensory neurons, and conveying its orders to a large set of subservient neurons that themselves cause muscle contractions.

Such cellular dictatorships are common for escape movements, especially in invertebrates. They also control other kinds of movements that are basically identical each time they occur, including cricket chirping.

Small Team Approach

But these dictator cells aren’t the whole story. Crayfish can trigger a tail-flip another way too – via another small set of neurons that effectively act as an oligarchy.

These “non-giant” escapes are very similar to those triggered by giant neurons, but begin slightly later and allow more flexibility in the details. Thus, when a crayfish is aware it is in danger and has more time to respond, it typically uses an oligarchy instead of its dictator.

Similarly, even if a fish’s Mauthner neuron is killed, the animal can still escape from dangerous situations. It can quickly make similar escape movements using a small set of other neurons, though these actions begin slightly later.

This redundancy makes sense: it would be very risky to trust escape from a predator to a single neuron, with no backup – injury or malfunction of that neuron would then be life-threatening. So evolution has provided multiple ways to initiate escape.

Neuronal oligarchies may also mediate our own high-level perceptions, such as when we recognize a human face.

Majority Wins

For many other behaviors, however, nervous systems make decisions through something like Sherrington’s “million-fold democracy.”

For example, when a monkey reaches out its arm, many neurons in its brain’s motor cortex generate spikes. Every neuron spikes for movements in many directions; but each has one particular direction that makes it spike the most.

Researchers hypothesized that each neuron contributes to all reaches to some degree, but spikes the most for reaches it’s contributing to most. To figure it out, they monitored many neurons and did some math.

Researchers measured the rate of spikes in several neurons when a monkey reached toward several targets. Then, for a single target, they represented each neuron by a vector – its angle indicates the neuron’s preferred reaching direction (when it spikes most) and the length indicates its relative rate of spiking for this particular target. They mathematically summed their effects (a weighted vector average) and could reliably predict the movement outcome of all the messages the neurons were sending.

This is like a neuronal election in which some neurons vote more often than others. An example is shown in the figure. The pale violet lines represent the movement votes of individual neurons. The orange line (the “population vector”) indicates their summed direction. The yellow line indicates the actual movement direction, which is quite similar to the population vector’s prediction. The researchers called this population coding.

For some animals and behaviors, it is possible to test the nervous system’s version of democracy by perturbing the election. For example, monkeys (and people) make movements called “saccades” to quickly shift the eyes from one fixation point to another. Saccades are triggered by neurons in a part of the brain called the superior colliculus. Like in the monkey reach example above, these neurons each spike for a wide variety of saccades but spike most for one direction and distance. If one part of the superior colliculus is anesthetized – disenfranchising a particular set of voters – all saccades are shifted away from the direction and distance that the now silent voters had preferred. The election has now been rigged.

A single-cell manipulation demonstrated that leeches also hold elections. Leeches bend their bodies away from a touch to their skin. The movement is due to the collective effects of a small number of neurons, some of which voted for the resulting outcome and some of which voted otherwise (but were outvoted).

If the leech is touched on the top, it tends to bend away from this touch. If a neuron that normally responds to touches on the bottom is electrically stimulated instead, the leech tends to bend in approximately the opposite direction (the middle panel of the figure). If this touch and this electrical stimulus occur simultaneously, the leech actually bends in an intermediate direction (the right panel of the figure).

This outcome is not optimal for either individual stimulus but is nonetheless the election result, a kind of compromise between two extremes. It’s like when a political party comes together at a convention to put together a platform. Taking into account what various wings of the party want can lead to a compromise somewhere in the middle.

Numerous other examples of neuronal democracies have been demonstrated. Democracies determine what we see, hear, feel and smell, from crickets and fruit flies to humans. For example, we perceive colors through the proportional voting of three kinds of photoreceptors that each respond best to a different wavelength of light, as physicist and physician Thomas Young proposed in 1802. One of the advantages of neuronal democracies is that variability in a single neuron’s spiking is averaged out in the voting, so perceptions and movements are actually more precise than if they depended on one or a few neurons. Also, if some neurons are damaged, many others remain to take up the slack.

Unlike countries, however, nervous systems can implement multiple forms of government simultaneously. A neuronal dictatorship can coexist with an oligarchy or democracy. The dictator, acting fastest, may trigger the onset of a behavior while other neurons fine-tune the ensuing movements. There does not need to be a single form of government as long as the behavioral consequences increase the probability of survival and reproduction.

Image Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto (MARS)

Source: The Conversation (by Dr. Ari Berkowitz)

After the missile struck their moon at an appreciable percentage of the speed of light, scientists manage to translate the message that followed its arrival; “That was a warning. We did not miss. The next one will be wrapped in Cobalt. Do not threaten us.”

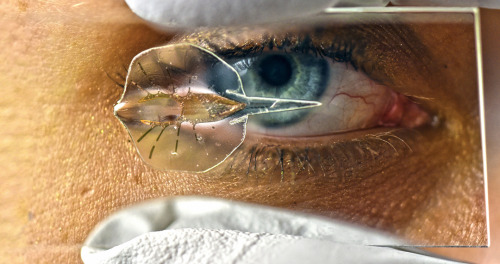

I’ll say it again: Scientists have created a synthetic stingray that’s propelled by living muscle cells and controlled by light.

!

But the ultimate goal isn’t a cyborg sea monster - it’s a human heart.

“I want to build an artificial heart, but you’re not going to go from zero to a whole heart overnight,” says Kit Parker, a bioengineer and physicist at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “This is a training exercise.”

Full, fascinating story here.

Starfish walking on land 😱🌠

Why Do Some People with Cystic Fibrosis Live Much Longer Than Others?

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital have found that longevity among patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) may be linked to their genes.

Studying over 600 patients with CF, the scientists found five individuals who stood out due to their age–in their 50s and 60s–and relative lung function. By sequencing the genomes of those five patients, the scientists found a set of rare and never-before-discovered genetic variants, related to so-called epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs), that might help explain their longevity and stable lung function.

“Our hypothesis is that these ENaC mutations help to rehydrate the airways of CF patients, making it less likely for detrimental bacteria to take up residence in the lungs,” said Ruobing Wang, MD, a pulmonologist at Boston Children’s.

Read more

Funding: This work was supported by the Gene Discovery Core of The Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, Boston Children’s Hospital; Gilda and Alfred Slifka, Gail and Adam Slifka and the CFMS Fund; the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skeletal Diseases; the National Institute of Health (NIH) (U54 HD090255, P30 DK079307); the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH (U19 HD077671); the May Family Fund; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc. (RO1 HL090136 and U01 HL100402 RFA-HL-09-004); and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R37HL51856).

Raise your voice in support of expanding federal funding for life-saving medical research by joining the AAMC’s advocacy community.

You are a space traveler from Earth. One day you land on a seemingly advanced planet where the aliens are friendly. You decide to live there and learn their language, and with their technology it takes barely a day. However, you soon offend the wrong person by accident and become arrested. It is decided that your punishment is death, and you are brought a vial of liquid that you are told is of the deadliest kind. Terrified, you drink it only to find out it’s water. Turns out that the very substance keeping you alive is deadly to these creatures. Write what happens following this discovery.

-

puppiesrulethisworld reblogged this · 1 month ago

puppiesrulethisworld reblogged this · 1 month ago -

jamalexlee reblogged this · 2 months ago

jamalexlee reblogged this · 2 months ago -

killeveryoneforever reblogged this · 3 months ago

killeveryoneforever reblogged this · 3 months ago -

killeveryoneforever liked this · 3 months ago

killeveryoneforever liked this · 3 months ago -

iamramonadestroyerofworlds reblogged this · 3 months ago

iamramonadestroyerofworlds reblogged this · 3 months ago -

iamramonadestroyerofworlds liked this · 3 months ago

iamramonadestroyerofworlds liked this · 3 months ago -

lunaraquaenby reblogged this · 4 months ago

lunaraquaenby reblogged this · 4 months ago -

vintagedaisywitch3 reblogged this · 4 months ago

vintagedaisywitch3 reblogged this · 4 months ago -

1ebilcat reblogged this · 4 months ago

1ebilcat reblogged this · 4 months ago -

aeshnacyanea2000 reblogged this · 4 months ago

aeshnacyanea2000 reblogged this · 4 months ago -

skullsenpai liked this · 4 months ago

skullsenpai liked this · 4 months ago -

koronbain-tenshidere reblogged this · 4 months ago

koronbain-tenshidere reblogged this · 4 months ago -

theundertaleeffect reblogged this · 5 months ago

theundertaleeffect reblogged this · 5 months ago -

theundertaleeffect liked this · 5 months ago

theundertaleeffect liked this · 5 months ago -

deathdefyinglifeleaps reblogged this · 5 months ago

deathdefyinglifeleaps reblogged this · 5 months ago -

irohuen liked this · 5 months ago

irohuen liked this · 5 months ago -

thesnug liked this · 6 months ago

thesnug liked this · 6 months ago -

annaq301v liked this · 6 months ago

annaq301v liked this · 6 months ago -

askinkabahatiyoksevmeseydimkeske reblogged this · 7 months ago

askinkabahatiyoksevmeseydimkeske reblogged this · 7 months ago -

tvijay liked this · 8 months ago

tvijay liked this · 8 months ago -

frootcentral reblogged this · 9 months ago

frootcentral reblogged this · 9 months ago -

littlegal100 reblogged this · 9 months ago

littlegal100 reblogged this · 9 months ago -

littlegal100 liked this · 9 months ago

littlegal100 liked this · 9 months ago -

fandomcrazygirl13 reblogged this · 9 months ago

fandomcrazygirl13 reblogged this · 9 months ago -

autumn-foxfire reblogged this · 9 months ago

autumn-foxfire reblogged this · 9 months ago -

amayukoatahitik liked this · 9 months ago

amayukoatahitik liked this · 9 months ago -

plasticlasagna liked this · 10 months ago

plasticlasagna liked this · 10 months ago -

justasmidgx liked this · 10 months ago

justasmidgx liked this · 10 months ago -

reallifecdcollector liked this · 10 months ago

reallifecdcollector liked this · 10 months ago -

nah-pa-que reblogged this · 10 months ago

nah-pa-que reblogged this · 10 months ago -

nah-pa-que liked this · 10 months ago

nah-pa-que liked this · 10 months ago -

milkhoney531 liked this · 10 months ago

milkhoney531 liked this · 10 months ago -

chocococo16 reblogged this · 10 months ago

chocococo16 reblogged this · 10 months ago -

laughter-like-a-headache reblogged this · 10 months ago

laughter-like-a-headache reblogged this · 10 months ago -

melodemonica reblogged this · 10 months ago

melodemonica reblogged this · 10 months ago -

melodemonica liked this · 10 months ago

melodemonica liked this · 10 months ago -

pertweefan1970 liked this · 11 months ago

pertweefan1970 liked this · 11 months ago -

thoseanimalsthere reblogged this · 11 months ago

thoseanimalsthere reblogged this · 11 months ago -

sowolonut liked this · 1 year ago

sowolonut liked this · 1 year ago -

jester-of-the-court liked this · 1 year ago

jester-of-the-court liked this · 1 year ago -

naturelandscapeblog reblogged this · 1 year ago

naturelandscapeblog reblogged this · 1 year ago -

lifelovebooksnshit liked this · 1 year ago

lifelovebooksnshit liked this · 1 year ago -

insanitori reblogged this · 1 year ago

insanitori reblogged this · 1 year ago -

insanitori liked this · 1 year ago

insanitori liked this · 1 year ago -

alinace reblogged this · 1 year ago

alinace reblogged this · 1 year ago -

sckaoc reblogged this · 1 year ago

sckaoc reblogged this · 1 year ago