“Lots Of Stories Written In These Ancient Papers, Showing A Lot. Good Moments, Bad Moments, Victories,

“Lots of stories written in these ancient papers, showing a lot. Good moments, bad moments, victories, defeats, lessons from the past. One small look in them can teach you what lies beneath those unlimited sands.”

More Posts from S-afshar and Others

Prof. Erol Manisali's Book Chapter about Me

Erol Manisali'nin Hakkımda Kitap Bölümü - Prof. Erol Manisali's Book Chapter about Me - Глава книги профессора Эрола Манисалы обо мне

1. Giriş – Introduction - Введение

Giriş

Rahmetli Prof. Dr. Erol Manisali (28/7/1940-29/10/2022) 2018 yılında yayınlanan kitaplarından birinde benim hakkımda bir bölüm yazmıştı; Kitabın adı 'Yolumun Kesiştiği Ünlüler'. Bu yeniden yayında, okuyucular art arda aşağıdaki materyali bulacaklar:

1- Türkçe, İngilizce ve Rusça kısa giriş,

2- bölümün metni (Türkçe),

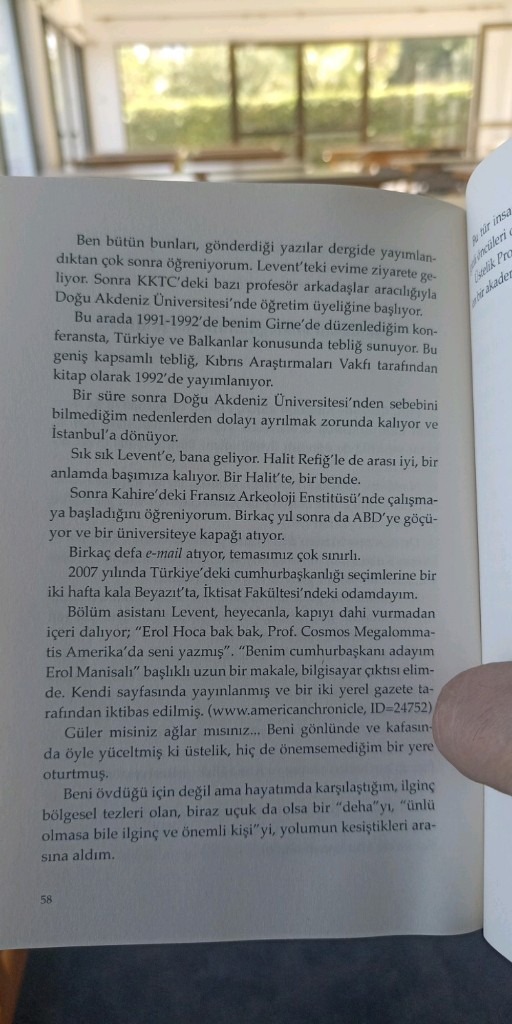

3- resim olarak bölüm sayfaları ve kitap kapağı,

4- bölümün İngilizce çevirisi,

5- bölümün Rusça çevirisi,

6- Türkçe olmayan okuyucular için açıklayıcı notlar (İngilizce ve Rusça),

7- kitap tanıtımı ve verileri (Türkçe, İngilizce ve Rusça olarak),

8- Prof. Manisali'nin kitap bölümünde bahsettiği makalelerime ve kitaplarıma bağlantılar ve

9- Prof. Manisali ile ilgili biyografik notlara ve ölüm ilanlarına bağlantılar.

Mevcut sunum tüm bölümlerinde üç dillidir.

Introduction

In one of his books (published in 2018), the late Prof. Dr. Erol Manisali (28/7/1940-29/10/2022) wrote a chapter about me; the book title is 'Celebrities I crossed in my Path'. In the present re-publication, readers will successively find the following material:

1- the brief introduction in Turkish, English and Russian,

2- the text of the chapter (in Turkish),

3- the chapter pages and the book cover as pictures,

4- the English translation of the chapter,

5- the Russian translation of the chapter,

6- explanatory notes for non-Turkish readership (in English and Russian),

7- book presentation and data (in Turkish, English and Russian),

8- links to my articles and books mentioned by Prof. Manisali in his book chapter, and

9- links to biographical notes about Prof. Manisali and obituaries.

The current presentation is trilingual in all its parts.

Введение

В одной из своих книг (опубликованной в 2018 году) покойный профессор доктор Эрол Манисалы (28.07.1940-29.10.2022) написал обо мне главу; название книги - «Знаменитости, которых я встретил на своем пути». В настоящем переиздании читатели последовательно найдут следующий материал:

1- краткое введение на турецком, английском и русском языках,

2- текст главы (на турецком языке),

3- страницы главы и обложка книги в виде картинок,

4- английский перевод главы,

5- русский перевод главы,

6- пояснения для нетурецких читателей (на английском и русском языках),

7- презентация книги и данные книги (на турецком, английском и русском языках),

8- ссылки на мои статьи и книги, упомянутые профессором Манисалы в главе его книги, и

9- ссылки на биографические заметки о профессоре Манисалы и некрологи.

Текущая презентация является трехъязычной во всех ее частях.

-------------------------------------------------------

2. Prof. Cosmas Megalommatis'in dramı

Prof. Cosmas Megalommatis, Fransa ye Almanya'da hem tarih hem arkeoloji doktoralari yapmış, Yunanistan, Kıbrıs, Mısır ve ABD'de öğretim üyeliği olan, Türkçe dahil 15 dil bilen bir deha.

Nasıl mı tanıştık? 1980'1erin ortası ... Aylık İngilizce Middle East Business and Banking dergisini çıkarıyorum; yurtiçi ye yurtdışından yazılar geliyor.

Dr. Andrew Mango'dan Alman profesor Werner Gumpel'e, Doğan Kuban'dan Mümtaz Soysal'a kadar iktisadi, siyasi, sosyal, kiiltiirel yazılar geliyor ye yayımlıyorum.

Dr. Cosmas Megalommatis isimli bir Yunanlıdan Iran üzerine bir makale gelmış; değerli buluyorum ye yayımlanıyor. Daha sonra birkaç yazı daha geliyor.

Birkaç ay sonra kendisi derginin bürosuna geliyor, tanışıyoruz. Çok ilginç bir insan. Bana hikâyesini de anlatıyor. Atina Üniversitesinde asistan kadrosunda; Paris'te bir Fransız profesörle uzun çalışmalar yapıyor; "Hellenizm yoktur, oryantalizm vardır," içerikli bir çalışma ortaya çıkıyor.

Atina'da bir yayıneviyle anlaşıyor, basılacak. Ancak Atina Patriği'nin haberi oluyor ve Atina Üniversitesi rektörüne rnektup yazarak. Dr. Megalommatis'i üniversiteden attırıyor.

Dr. Cosmas çok kızıyor ye Yunanistan'ı terk ediyor. Hatta patriğe kızgınlığından Ortodoks mezhebinden ayrılarak Kahire'de Müslüman oluyor.

Ben bütün bunları gönderdiği yazılar dergide yayımlamdıktan çok sonra öğreniyorum. Levent'deki evime ziyarete geliyor. Sonra KKTC'deki bazı profesör arkadaşlar aracılığıyla Doğu Akdeniz Üniversitesi'nde öğretim üyeliğine başlıyor.

Bu arada 1991-1992'de benim Girne'de düzenlediğim konferansta, Türkiye ve Balkanlar konusunda tebliğ sunuyor. Bu geniş kapsamlı tebliğ, Kıbrıs Araştırmaları Vakfı tarafından kitap olarak 1992'de yayımlanıyor.

Bir sure sonra Doğu Akdeniz Üniversitesi'nde sebebini bilmediğim nedenlerden dolayı ayrılmak zorunda kalıyor ve Istanbul'a dönüyor.

Sık sık Levent'e bana geliyor. Halit Refiğ'le arası iyi, bir anlamda başımıza kalıyor. Bir Halit'te, bir bende.

Sonra Kahire'deki Fransız Arkeoloji Enstitüsü'nde çalışmaya başladığını öğreniyorum. Birkaç yıl sonra ABD'ye göçüyor ve bir üniversiteye kapağı atıyor.

Birkaç defa e-mail atıyor, temasımız çok sınırlı.

2007 yılında Türkiye'deki cumhurbaşkanlığı seçimlerine bir iki hafta kala Beyazit'ta Iktisat Fakültesi'ndeki odamdayım.

Bölüm asistanı Levent, heyencanla, kapıyı dahi vurmadan içeri dalıyor; "Erol Hoca bak bak, Prof. Cosmas Megalommatis Amerika'da seni yazmış". "Benim cumhurbaşkanı adayım Erol Manisalı" başlıklı uzun bir makale, bilgisayar çıktısı elimde. Kendi sayfasında yayınlamış ve bir iki yerel gazete tarafından iktibas edilmiş (www.americanchronicle, ID=24752).

Güler misiniz ağlar misiniz …. Beni gönlünde ve kafasında öyle yüceltmiş ki üstelik, hiç de önemsemediğim bir yere otutmuş.

Beni övdüğü için değil ama hayatımda karşılaştığım, ilginç bölgesel tezleri olan, biraz uçuk da olsa bir "daha"yı, "ünlü olmasa bile ilginç ve önemli kişi"yi, yolumun kesiştikleri arasına aldım.

Bu tür insanlar çok azınlıkta kalsalar bile yeni görüşlerin gizli öncüleri olmuşlardır.

Üstelik Prof. Megalommatis, 15 dünya dilini derinliğine bilen bir akademisyen.

--------------------------------------------------------------

3. Bölüm sayfaları ve kitap kapağı - Chapter pages and the book cover - страницы главы и обложка книги

---------------------------------------------------

4. Prof. Cosmas Megalommatis' drama

Prof. Cosmas Megalommatis prepared two doctorates in History and Archeology, in France and Germany,

He is a genius, who taught in Greece, Cyprus, Egypt and the USA, and speaks 15 languages, including Turkish.

How did we meet? Mid 1980's ... I publish the monthly English magazine Middle East Business and Banking; articles are coming from home and abroad.

From Dr. Andrew Mango to German professor Werner Gumpel, from Doğan Kuban to Mümtaz Soysal, I receive and publish economic, political, social and cultural articles.

An article on Iran came from a Greek named Cosmas Megalommatis; I found it valuable and it was published. A few more articles followed.

A few months later, he came to the magazine's office and we met. He was a very interesting person. He also told me his story. He belonged to the cadre of assistants at the University of Athens; he had been doing long studies with a French professor in Paris; a study with the content "There is no Hellenism, there is Orientalism" emerged.

He contracted with a publishing house in Athens; the study would be published. However, the Patriarch of Athens was informed and he wrote a letter to the rector of the University of Athens. Dr. Megalommatis is kicked out of the university.

Dr. Cosmas got very angry and left Greece. He even became a Muslim in Cairo by leaving the Orthodox sect, out of anger at the patriarch.

I learned about all these developments long after the articles that he sent were published in the magazine. He came to visit me in my house in Levent1. Then, through some friends, who were professors in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, he started his teaching career at Eastern Mediterranean University.

By the way, he presented a paper on Turkey and the Balkans at the conference that I held in Girne2 in 1991-1992. This comprehensive paper was published as a book by the Cyprus Studies Foundation in 1992.

After a while, he had to leave the Eastern Mediterranean University for reasons I don't know, and he returned to Istanbul.

He often came to me in Levent. He was on good terms with Halit Refiğ3, and in a way he was up to us. Once in Halit's; once in my house.

Then, I learned that he started working at the French Archaeological Institute in Cairo. A few years later, he immigrated to the USA and went to a university.

He sent e-mails a few times; our contact was very limited.

One or two weeks before the 2007 presidential elections in Turkey, I was in my office at the Faculty of Economics in Beyazit4.

My Department assistant, Mr. Levent5, burst in excitedly, without even knocking on the door; "Professor Erol, look! Prof. Cosmas Megalommatis wrote about you in America". I have a long article titled "My presidential candidate is Erol Manisalı", a computer printout. Published on its own page and quoted by a few local newspapers (www.americanchronicle, ID=24752)6.

Would you laugh or cry …. He exalted me so much in his heart and mind that he made me sit in a place that I didn't care at all about.

Not because he praised me, but for having encountered in my life a man with regionally interesting approaches, albeit somewhat eccentric, an interesting and important person, who crossed my path, I included him in this book, although he is not famous.

Such people, though very few, have been the secret pioneers of new ideas.

Moreover, Prof. Megalommatis is an academic who has deep knowledge of 15 world languages.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

5. Драма профессора Космы Мегаломматиса

Профессор Космас Мегаломматис подготовил две докторские степени по истории и археологии во Франции и Германии.

Он гений, который преподает в Греции, на Кипре, в Египте и США и говорит на 15 языках, включая турецкий.

Как мы познакомились? Середина 1980-х ... Я издаю ежемесячный английский журнал Middle East Business and Banking; Статьи поступают из дома и за рубежом.

От доктора Эндрю Манго до немецкого профессора Вернера Гумпеля, от Догана Кубана до Мюмтаз Сойсал, я получаю и публикую экономические, политические, социальные и культурные статьи.

Статья об Иране была написана греком Космасом Мегаломматисом; Я нахожу это ценным, и оно опубликовано. Далее еще несколько статей.

Через несколько месяцев он приходит в редакцию журнала, и мы встречаемся. Он очень интересный человек. Он также рассказывает мне свою историю. Он принадлежит к числу ассистентов Афинского университета; он долго учился у французского профессора в Париже; появляется исследование с содержанием «Нет эллинизма, есть ориентализм».

Заключен контракт с издательством в Афинах, оно будет опубликовано. Однако Патриарх Афин был проинформирован и написал письмо ректору Афинского университета. Доктора Мегаломматиса выгнали из университета.

Доктор Космас очень злится и уезжает из Греции. Он даже стал мусульманином в Каире, выйдя из православной секты, из гнева на патриарха.

Обо всех этих событиях я узнал уже давно после того, как статьи, которые он присылал, были опубликованы в журнале. Он пришел навестить меня в моем доме в Левенте1. Затем через друзей, которые были профессорами в Турецкой Республике Северного Кипра, он начал свою преподавательскую деятельность в Университете Восточного Средиземноморья.

Кстати, он выступал с докладом о Турции и Балканах на конференции, которую я проводил в Гирне2 в 1991-1992 годах. Этот всеобъемлющий документ был опубликован в виде книги Фондом кипрских исследований в 1992 году.

Через некоторое время ему пришлось покинуть Восточно-Средиземноморский университет по непонятным мне причинам, и он вернулся в Стамбул.

Он часто приезжал ко мне в Левент. Он был в хороших отношениях с Халитом Рефигом3 и в чем-то нам подчинялся. Однажды у Халита; однажды в моем доме.

Потом я узнал, что он начал работать во Французском археологическом институте в Каире. Через несколько лет он иммигрировал в США и поступил в университет.

Он отправил электронные письма несколько раз; наши контакты были очень ограничены.

За одну или две недели до президентских выборов 2007 года в Турции я был в своем кабинете на экономическом факультете в Беязите4.

Мой ассистент, господин Левент5, взволнованно ворвался, даже не постучав в дверь; «Профессор Эрол, смотрите! Профессор Космас Мегаломматис писал о вас в Америке». У меня есть длинная статья под названием «Мой кандидат в президенты — Эрол Манисалы», компьютерная распечатка. Публикуется на собственной странице и цитируется несколькими местными газетами (www.americanchronicle, ID=24752) 6.

Вы бы смеяться или плакать .... Он так возвеличил меня в своем сердце и разуме, что заставил меня сесть на место, которое меня совершенно не заботило.

Не за то, что он хвалил меня, а за то, что встретил в своей жизни человека с регионально интересными подходами, хотя и несколько эксцентричного, интересного и важного человека, перешедшего мне дорогу, я включил его в эту книгу, хотя он и не известен.

Такие люди, хотя и очень немногие, были тайными пионерами новых идей.

Кроме того, профессор Мегаломматис является академиком, обладающим глубоким знанием 15 языков мира.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

6. Notlar - Notes - Примечания

Notes for non-Turkish readership in English & Russian:

1. Levent is a district in Istanbul.

2. Girne was also known as Keryneia.

3. Halit Refiğ (1934-2009) was one of Turkey's foremost film directors, film producers, screenwriters and writers.

4. Beyazit is a district in Istanbul.

5. Levent is also a Turkish personal name for men.

6. The correct link would be: https://www.americanchronicle.com/articles/24752

However, the site was hacked and closed down 2014.

Примечания на английском и русском языках (для нетурецких читателей):

1. Левент – район в Стамбуле.

2. Гирне также была известна как Кириния.

3. Халит Рефиг (1934-2009) был одним из ведущих турецких режиссеров, продюсеров, сценаристов и писателей.

4. Беязит — район в Стамбуле.

5. Левент также является турецким личным мужским именем.

6. Правильная ссылка: https://www.americanchronicle.com/articles/24752.

Однако в 2014 году сайт был взломан и закрыт.

---------------------------------------------------------

7- Kitap tanıtımı ve verileri - Book presentation and data - Презентация книги и данные книги

Prof. Manisali'nin kitabının adı:

Prof. Manisali's book title:

Название книги профессора Манисалы:

Erol Manisalı, Yolumun Kesiştiği Ünlüler

Erol Manisali, Celebrities I crossed in my Path

Эрол Манисалы, Знаменитости, которых я встретил на своем пути

Kitap hakkında

Prof. Dr. Erol Manisalı akademik çalışmaları sırasında ve yazarlık yaşamı boyunca tanıştığı yerli-yabancı ünlü simalarla ilgili anılarını paylaşıyor. Siyasetçiler, sanatçılar, bilim insanları, işadamları, Manisalı’nın gözlem gücünün süzgecinden geçerek, Türkiye’nin yakın tarihinde bıraktıkları izlerle yer alıyorlar Yolumun Kesiştiği Ünlüler’de.

Bülent Ecevit’ten Kirk Douglas’a, Süleyman Demirel’den Vehbi Koç ve Sakıp Sabancı’ya, Turgut Özal’dan Attila İlhan’a, Mümtaz Soysal’dan İlhan Selçuk’a, General Franco’dan Zekeriya Öz’e açılan yelpazede pek çok ismin adeta resmi geçit yaptığı elinizdeki kitap, hem bir anılar demeti, hem de yakın dönem siyaset notları niteliği taşıyor.

Yolumun Kesiştiği Ünlüler, Avrupa Birliği’yle ilişkileri, Kıbrıs sorununu, Ergenekon operasyonlarını, din sömürüsü ve darbeleri, Erol Manisalı’nın ilk kez dile getirdiği gerçekler ve yaşanmışlıklar temelinde yeniden yorumluyor.

"Yolumun kesiştiği ünlü kişiler ile olaylar arasındaki bağlar bazen üzücü bazen de trajikomik özellikler içeriyor. Bunları kamuoyuna aktarmadığım takdirde, ortaya çıkmaları mümkün olmayacaktı. Sadece benim hafızamda saklı kalmalarını istemedim".

About the book

Prof. Dr. Erol Manisalı shares his memories of famous local and foreign faces he met during his academic studies and throughout his writing life. Politicians, artists, scientists, businessmen take their place in 'Celebrities I crossed in my Path' with the traces they left in Turkey's recent history, passing through the filter of the observation power of Manisalı.

From Bülent Ecevit to Kirk Douglas, from Süleyman Demirel to Vehbi Koç and Sakıp Sabancı, from Turgut Özal to Attila İlhan, from Mümtaz Soysal to İlhan Selçuk, from General Franco to Zekeriya Öz. The book in your hand, in which many names have made an official parade, is both a bundle of memories and notes on recent politics.

'Celebrities I crossed in my Path' reinterprets the relations with the European Union, the Cyprus problem, the Ergenekon operations, religious exploitation and coups based on the facts and experiences that Erol Manisalı first voiced.

"The ties between the famous people I crossed with and the events sometimes contain sad and sometimes tragicomic features. If I did not make them public, they would not have been possible. I just didn't want them to remain hidden in my memory".

О книге

Профессор доктор Эрол Манисалы делится своими воспоминаниями об известных местных и иностранных лицах, с которыми он встречался во время учебы и на протяжении всей своей писательской жизни. Политики, художники, ученые, бизнесмены занимают свое место в «Знаменитости, которых я встретил на своем пути» со следами, которые они оставили в новейшей истории Турции, пройдя через фильтр наблюдательной силы Манисалы.

От Бюлента Эджевита до Кирка Дугласа, от Сулеймана Демиреля до Вехби Коча и Сакипа Сабанджи, от Тургута Озала до Аттилы Ильхана, от Мюмтаза Сойсала до Ильхана Сельчука, от генерала Франко до Зекерии Оз. Книга в вашей руке, в которой многие имена сделали официальный парад, представляет собой одновременно пачку воспоминаний и заметок о недавней политике.

«Знаменитости, которых я встретил на своем пути» переосмысливает отношения с Европейским Союзом, кипрскую проблему, операции «Эргенекон», религиозную эксплуатацию и перевороты на основе фактов и опыта, которые впервые озвучил Эрол Манисалы.

«Связи между известными людьми, с которыми я пересекался, и событиями иногда содержат печальные, а иногда и трагикомические черты. Если бы я не обнародовал их, они были бы невозможны. Я просто не хотел, чтобы они оставались скрытыми в моей памяти».

Kitap verileri / Book data / Данные книги

KIRMIZI KEDİ YAYINEVİ

Yayın Tarihi: 19.03.2018

ISBN: 9786050980936

Dil: TÜRKÇE

Sayfa Sayısı: 120

Cilt Tipi: Karton Kapak

Kağıt Cinsi: Kitap Kağıdı

Boyut: 13.5 x 19.5 cm

--------------

RED CAT PUBLISHING HOUSE

Release Date: 19.03.2018

ISBN: 9786050980936

Language Turkish

Number of Pages: 120

Binding Type: Paperback

Paper Type: Book Paper

Size: 13.5 x 19.5 cm

--------------------

ИЗДАТЕЛЬСТВО КРАСНЫЙ КОТ

Дата выхода: 19.03.2018

ISBN: 9786050980936

Язык Турецкий

Количество страниц: 120

Тип переплета: Мягкая обложка

Тип бумаги: Книжная бумага

Размер: 13,5 х 19,5 см

---------------------------------------------

8. Prof. Manisali'nin kitap bölümünde bahsettiği makalelerime ve kitaplarıma bağlantılar - Links to my articles and books mentioned by Prof. Manisali in his book chapter - Ссылки на мои статьи и книги, упомянутые профессором Манисалы в главе его книги

Prof. Manisalı ile ilgili yazdığım yazının linkleri:

Links to my article about Prof. Manisali:

Ссылки на мою статью о профессоре Манисалы:

![Erol Manisali for President of Turkey (18th April 2007) - [DOCX Document]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/b1fe1889d22e1e7ad00ceee4b67e5839/a6ac1736a8f0d038-57/s1280x1920/579ae1d8d0fc10cbc7afa4624eca3eda7e5cf436.jpg)

Prof. Manisali'nin kitabının bölümünde adı geçen konuşmamın ve kitabın yayınlandığı linkler:

Links to the publication of my speech and the book that are mentioned in the chapter of the Prof. Manisali's book:

Ссылки на публикацию моего выступления и на книгу, которые упоминаются в главе книги профессора Манисалы:

-------------------------------------------------------------

9. Prof. Manisali ile ilgili biyografik notlara ve ölüm ilanlarına bağlantılar - Links to biographical notes about Prof. Manisali and obituaries - Ссылки на биографические заметки о профессоре Манисалы и некрологи

The verso of the Narmer Palette. Narmer, considered by many Egyptologists to be the first ruler of a unified Egypt, stands over a defeated foe and is about to bring his mace down on the foe's head. Narmer is shown here wearing the white crown (hedyet) of Lower Egypt, while on the recto he is depicted with the red crown (desheret) of Upper Egypt, perhaps symbolizing his unification of the two realms. Artist unknown; sculpted ca. 3200-3000 BCE. Found at Hierakonpolis (Nekhen), pre-unification capital of Upper Egypt; now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Photo credit: Heagy1/Wikimedia Commons.

Οι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν (Σιρβάν-σαχ) και το Ανάκτορό τους στο Μπακού του Αζερμπαϊτζάν

The Shahs of Shirvan (Shirvanshahs) and their Palace in Baku, Azerbaijan

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 2η Σεπτεμβρίου 2019.

Ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης αναπαράγει τμήμα διάλεξής μου στο Πεκίνο τον Ιανουάριο του 2018 για τα υπαρκτά και τα ανύπαρκτα έθνη του Καυκάσου, την ιστορική συνέχεια πολιτισμικής παράδοσης, την ιστορική ασυνέχεια ορισμένων διεκδικήσεων, καθώς και την σωστή κινεζική πολιτική στον Καύκασο. Στο σημείο αυτό, η ιστορική συνέχεια της προϊσλαμικής Ατροπατηνής στο ισλαμικό Αζερμπαϊτζάν καθιστά ταυτόχρονα το Αζερμπαϊτζάν "Ιράν" και το Ιράν "περιφέρεια του Αζερμπαϊτζάν".

---------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/02/οι-σάχηδες-του-σιρβάν-σιρβάν-σαχ-και-τ/ ================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Η περιοχή του Σιρβάν είναι το κέντρο του σημερινού Αζερμπαϊτζάν και ονομαζόταν έτσι από τα προϊσλαμικά χρόνια, όταν ο όλος χώρος του Αζερμπαϊτζάν και του βορειοδυτικού Ιράν ονομαζόταν Αδουρμπαταγάν, λέξη από την οποία προέρχεται η ονομασία του σύγχρονου κράτους και η οποία αποδόθηκε στα αρχαία ελληνικά ως Ατροπατηνή.

Το Σιρβάν βρισκόταν στα βόρεια όρια του ιρανικού κράτους και, όταν αυτό βρισκόταν σε κατάσταση παρακμής, αδυναμίας και προβλημάτων, συχνά ντόπιοι Ατροπατηνοί ηγεμόνες σχημάτιζαν μια ανεξάρτητη τοπική αρχή. Συνεπώς, ο τίτλος ‘Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν’ ανάγεται ήδη σε προϊσλαμικά χρόνια και μουσουλμάνοι ιστορικοί μας πληροφορούν ότι ένας ‘Σάχης του Σιρβάν’ προσπάθησε να ανακόψει εκεί τα επελαύνοντα ισλαμικά στρατεύματα τα οποία στα μισά του 7ου αιώνα έφθασαν και εκεί, όταν κατέρρευσε το σασανιδικό Ιράν. Το γιατί είχε το Σιρβάν γίνει ανεξάρτητο βασίλειο σε χρονιές όπως 630 ή 650 μπορούμε να καταλάβουμε πολύ εύκολα.

Οι συνεχείς εξουθενωτικοί πόλεμοι Ρωμανίας και Ιράν (601-628), και η αντεπίθεση του Ηράκλειου με σκοπό να αποσπάσει τον Τίμιο Σταυρό από τον Χοσρόη Β’ και να εκδιώξει τους Ιρανούς από την Αίγυπτο και την Συρο-Παλαιστίνη είχαν ήδη ολότελα εξαντλήσει και τις δύο αυτοκρατορίες πριν εμφανιστούν στον ορίζοντα τα στρατεύματα του Ισλάμ.

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν στο Μπακού

Το Σιρβάν καταλήφθηκε από τα ισλαμικά στρατεύματα (που πολεμούσαν υπό τις διαταγές του Σαλμάν ιμπν Ράμπια αλ Μπαχίλι) και μάλιστα αυτά έφθασαν βορειώτερα στον Καύκασο, αλλά στην τεράστια περιοχή που έλεγχε πρώτα το ομεϋαδικό και μετά το 750 το αβασιδικό χαλιφάτο, από την βορειοδυτική Αφρική μέχρι την Κίνα και την Ινδια, το Σιρβάν ήταν και πάλι ένα είδος περιθωρίου: δεν ήταν ούτε καν ένα σημαντικό σύνορο επειδή μετά το Σιρβάν δεν υπήρχε ένα μεγάλο αντίπαλο κράτος.

Αντίθετα, αυτό συνέβαινε ήδη σε άλλες περιοχές όπως στην Ανατολία (Ρωμανία), την Κεντρική Ασία (Κίνα), την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού (το κράτος του Χάρσα), και την Αίγυπτο (χριστιανική Νοβατία και Μακουρία).

Έτσι, αφού το Σιρβάν διοικήθηκε από μια σειρά διαδοχικών απεσταλμένων των χαλίφηδων (όπως για παράδειγμα, στα χρόνια του Αβασίδη Χαλίφη Χαρούν αλ Ρασίντ, ο Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazid_ibn_Mazyad_al-Shaybani), από τις αρχές του 9ου αιώνα οι απόγονοι του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι δημιούργησαν μια τοπική δυναστεία (γνωστή ως Γιαζιντίδες – άσχετοι από τους Γιαζιντί) που ανεγνώριζε την χαλιφατική αρχή της Βαγδάτης.

Ανατολική Μικρά Ασία, Βόρεια Μεσοποταμία, ΒΔ Ιράν και Καύκασος από το 1100 στο 1300

Μετά την αρχή της αβασιδικής παρακμής όμως, στο δεύτερο μισό του 9ου αιώνα, ο εγγονός του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι διεκήρυξε την ανεξαρτησία του από το χαλιφάτο της Βαγδάτης και έλαβε εκνέου τον ιστορικό τίτλο του Σάχη του Σιρβάν. Ο Χάυθαμ ιμπν Χάλεντ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haytham_ibn_Khalid) ήταν λοιπόν ο πρώτος από τους μουσουλμάνους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν.

Γι’ αυτούς χρησιμοποιούνται σήμερα πολλά ονόματα που μπορεί να μπερδέψουν ένα μη ειδικό: Μαζιαντίδες (Mazyadids), Σαϋμπανίδες (Shaybanids), ή όπως προανέφερα Γιαζιντίδες (Yazidids). Αλλά εύκολα μπορείτε να προσέξετε ότι όλα αυτά αποτελούν απλώς διαφορετικές επιλογές συγχρόνων δυτικών ισλαμολόγων και ιστορικών από τα διάφορα ονόματα του ίδιου προσώπου: του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazid_ibn_Mazyad_al-Shaybani).

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν κτίσθηκε τον 15ο αιώνα όταν οι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν μετέφεραν την πρωτεύουσά τους από την Σεμάχα (βόρειο Αζερμπαϊτζάν) που είχε καταστραφεί από σεισμούς στο Μπακού. Σχέδιο από: Ismayil Mammad

Αν και αραβικής καταγωγής ως δυναστεία, οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν βρέθηκαν σε ένα κοινωνικό-πολιτισμικό πλαίσιο Αζέρων, Ιρανών και Τουρανών και σταδιακά εξιρανίσθηκαν έντονα κι άρχισαν να παίρνουν ονόματα βασιλέων και ηρώων από το ιρανικό-τουρανικό έπος Σαχναμέ του οποίου η πιο μνημειώδης και πιο θρυλική καταγραφή ήταν αυτή του Φερντοουσί. Έτσι λοιπόν αρχής γενομένης από τον Γιαζίντ Β’ του Σιρβάν (ο οποίος βασίλευσε στην περίοδο 991-1027), οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν είθισται να αποκαλούνται και ως Κασρανίδες (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasranids), επωνυμία που παραπέμπει σε ιρανικά βασιλικά ονόματα επικού και μυθικού χαρακτήρα. Αλλά πρόκειται για την ίδια πάντοτε δυναστεία.

Διακοσμήσεις με αραβουργήματα

Στην συνέχεια, οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν περιήλθαν διαδοχικά σε καθεστώς υποτέλειας προς τους Σελτζούκους, τους Μπαγκρατίδες της Γεωργίας (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagrationi_dynasty), τους Τουρανούς Κιπτσάκ (Kipchak) Ελντιγκουζίδες (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eldiguzids), και τους Μογγόλους Τιμουρίδες.

Όμως η σύγκρουσή τους με τον Τουρκμένο Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ, αρχηγό του τουρκμενικού αιρετικού τάγματος των Σούφι στην περίοδο 1447-1460 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaykh_Junayd), και ο θάνατος του εν λόγω σεΐχη στην μάχη του Χατσμάς (αζερ. Xaçmaz – αγγλ. Khachmaz) δημιούργησαν ένα τρομερό προηγούμενο.

Το μυστικό στρατιωτικό τάγμα των Κιζιλμπάσηδων (το οποίο οργανώθηκε ως στρατιωτική υποστήριξη του μυστικιστικού τάγματος των Σούφι από τον γιο του Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ, Σεΐχη Χαϋντάρ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaykh_Haydar), διατήρησε έντονη μνησικακία προς τους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν, μια σειρά καταστροφικών πολέμων στην ευρύτερη περιοχή του Καυκάσου επακολούθησε κατά την περίοδο 1460-1488, και τελικά και ο Σεΐχης Χαϋντάρ βρήκε και αυτός οικτρό τέλος μαζί με όλους τους στρατιώτες του στην μάχη του Ταμπασαράν (σήμερα στο Νταγεστάν), όπου αντιμετώπισε συνασπισμένους τους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν και τους Ακκουγιουλού (Τουρκμένους Ασπροπροβατάδες).

Και τελικά το 1500-1501, ο εγγονός του Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ και γιος του Σεΐχη Χαϋντάρ, Ισμαήλ, επήρε εκδίκηση καταλαμβάνοντας το Σιρβάν και σκοτώνοντας τον Φαρούχ Γιασάρ, τελευταίο Σάχη του Σιρβάν, και την φρουρά του. Επακολούθησε μια βίαιη επιβολή σιιτικών δογμάτων στον τοπικό πληθυσμό και μια απίστευτη τυραννία ως εκδίκηση για την στάση των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν εναντίον των Σιιτών, των Σούφι και των Κιζιλμπάσηδων. Ο Ισμαήλ Α’ ανέτρεψε και το κράτος των Ακκουγιουλού ιδρύοντας την σαφεβιδική (σουφική) δυναστεία του Ιράν.

Η μάχη του Σάχη Ισμαήλ Α’ με τον Φαρούχ Γιασάρ, τελευταίο Σάχη του Σιρβάν από σμικρογραφία ιρανικού σαφεβιδικού χειρογράφου (1501)

Μόνον η νίκη του Σουλτάνου Σελίμ Α’ το 1514 στο Τσαλντιράν εμπόδισε το κιζιλμπάσικο τσουνάμι να καταλάβει όλη την επικράτεια του Ισλάμ.

Η δυναστεία των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν μετά από 640 χρόνια πήρε έτσι ένα τέλος, αλλά έμειναν κορυφαίες δημιουργίες στον τομέα της ισλαμικής τέχνης και αρχιτεκτονικής να μας θυμίζουν την προσφορά της.

Μερικοί από τους μεγαλύτερους επικούς ποιητές, πανσόφους επιστήμονες, και σημαντικώτερους μυστικιστές των ισλαμικών χρόνων, ο Νεζαμί Γκαντζεβί, ο Αφζαλεντίν Χακανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khaqani) και ο Τζαμάλ Χαλίλ Σιρβανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nozhat_al-Majales) έζησαν στο Σιρβάν και οι απαγγελίες τους ακούστηκαν στο ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν.

Όμως το τέλος της δυναστείας του Σιρβάν άφησε μέχρι τις μέρες μας μια βραδυφλεγή βόμβα, πολύ καλά κρυμμένη, που κανένας δεν ξέρει σε ποιο βαθμό μας απειλεί όλους ακόμη και σήμερα με ένα απίστευτο αιματοκύλισμα.

Πολλοί προσπάθησαν σε διαφορετικές στιγμές να απενεργοποιήσουνν αυτή την βόμβα και να εξαφανίσουν την απειλή. Ωστόσο και αυτοί στην προσπάθειά τους έχυσαν πολύ αίμα που ακόμη και σήμερα παίζει ένα σημαντικό ρόλο. Η καλά κρυμμένη αυτή απειλή κι ανθρώπινη βόμβα έχει ένα όνομα που θα έπρεπε να κάνει την Ανθρωπότητα να τρέμει:

– Κιζιλμπάσηδες!

Αυτοί είναι οι κυρίαρχοι της αέναης υπομονής και της ατέρμονος προσμονής. Και αν και υπάρχουν πολλές ενδείξεις για τις δραστηριότητές τους, κανένας δεν μπορεί σήμερα να πει αν όντως υπάρχουν και αν διατηρούν την δύναμη που φημίζονταν να έχουν. Για το θέμα μπορούμε να βρούμε μόνον νύξεις κι υπαινιγμούς.

Σ’ αυτό ωστόσο θα επανέλθω. Στην συνέχεια μπορείτε να δείτε ένα βίντεο-ξενάγηση στο Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν και να διαβάσετε σχετικά με τα εκεί μνημεία, την πόλη και την δυναστεία που αποτελεί την ραχοκοκκαλιά της Ισλαμικής Ιστορίας του Αζερμπαϊτζάν. Επιπλέον συνδέσμους θα βρείτε στο τέλος.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Дворец ширваншахов – Shirvanshahs Palace, Baku – Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν

https://www.ok.ru/video/1495285893741

Περισσότερα:

Дворец ширваншахов (азерб. Şirvanşahlar sarayı) — бывшая резиденция ширваншахов (правителей Ширвана), расположенная в столице Азербайджана, городе Баку.

Образует комплекс, куда помимо самого дворца также входят дворик Диван-хане, усыпальница ширваншахов, дворцовая мечеть 1441 года с минаретом, баня и мавзолей придворного учёного Сейида Яхья Бакуви. Дворцовый комплекс был построен в период с XIII[3] по XVI век (некоторые здания, как и сам дворец, были построены в начале XV века при ширваншахе Халил-улле I). Постройка дворца была связана с переносом столицы государства Ширваншахов из Шемахи в Баку.

Несмотря на то, что основные постройки ансамбля строились разновременно, дворцовый комплекс производит целостное художественное впечатление. Строители ансамбля опирались на вековые традиции ширвано-апшеронской архитектурной школы. Создав чёткие кубические и многогранные архитектурные объёмы, они украсили стены богатейшим резным узором, что свидетельствует о том, что создатели дворца прекрасно владели мастерством каменной кладки. Каждый из зодчих благодаря традиции и художественному вкусу воспринял архитектурный замысел своего предшественника, творчески развил и обогатил его. Разновременные постройки связаны как единством масштабов, так и ритмом и соразмерностью основных архитектурных форм — кубических объёмов зданий, куполов, порталов.

В 1964 году дворцовый комплекс был объявлен музеем-заповедником и взят под охрану государства. В 2000 году уникальный архитектурный и культурный ансамбль, наряду с обнесённой крепостными стенами исторической частью города и Девичьей башней, был включён в список Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО. Дворец Ширваншахов и сегодня считается одной из жемчужин архитектуры Азербайджана.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Palace of the Shirvanshahs – Şirvanşahlar Sarayı – Дворец ширваншахов

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240287

Περισσότερα:

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs (Azerbaijani: Şirvanşahlar Sarayı, Persian: کاخ شروانشاهان) is a 15th-century palace built by the Shirvanshahs and described by UNESCO as “one of the pearls of Azerbaijan’s architecture”. It is located in the Inner City of Baku, Azerbaijan and, together with the Maiden Tower, forms an ensemble of historic monuments inscribed under the UNESCO World Heritage List of Historical Monuments. The complex contains the main building of the palace, Divanhane, the burial-vaults, the shah’s mosque with a minaret, Seyid Yahya Bakuvi’s mausoleum (the so-called “mausoleum of the dervish”), south of the palace, a portal in the east, Murad’s gate, a reservoir and the remnants of a bath house. Earlier, there was an ancient mosque, next to the mausoleum. There are still ruins of the bath and the lamb, belong to the west of the tomb.

In the past, the palace was surrounded by a wall with towers and, thus, served as the inner stronghold of the Baku fortress. Despite the fact that at the present time no traces of this wall have survived on the surface, as early as the 1920s, the remains of apparently the foundations of the tower and the part of the wall connected with it could be distinguished in the north-eastern side of the palace.

There are no inscriptions survived on the palace itself. Therefore, the time of its construction is determined by the dates in the inscriptions on the architectural monuments, which refer to the complex of the palace. Such two inscriptions were completely preserved only on the tomb and minaret of the Shah’s mosque. There is a name of the ruler who ordered to establish these buildings in both inscriptions is the – Shirvan Khalil I (years of rule 1417–1462). As time of construction – 839 (1435/36) was marked on the tomb, 845 (1441/42) on the minaret of the Shah’s mosque.

The burial vault, the palace and the mosque are built of the same material, the grating and masonry of the stone are the same.

The plan of the palace

The Palace

Divan-khana

Seyid Mausoleum Yahya Bakuvi

The place of the destroyed Kei-Kubad mosque

The Eastern portal

The Palace Mosque

The Shrine

Place of bath

Ovdan

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν (Σιρβάν-σαχ), Μπακού – Αζερμπαϊτζάν

Περισσότερα:

Τα ανάκτορα των Σιρβανσάχ (αζερικά: Şirvanşahlar Sarayı) είναι ανάκτορο κατασκευασμένο στο Μπακού, Αζερμπαϊτζάν, τον 13ο έως 16ο αιώνα.

Το ανάκτορο κατασκευάστηκε από τη δυναστεία των Σιρβανσάχ κατά τη διάρκεια της βασιλείας του Χαλίλ-Ουλλάχ, όταν η πρωτεύουσα μετακινήθηκε από τη Σαμάχι στο Μπακού.

Το ανάκτορο αποτελεί αρχιτεκτονικά συγκρότημα με το περίπτερο Ντιβανχανά, το ιερό των Σιρβανσάχ, το τζαμί του παλατιού, χτισμένο το 1441, μαζί με το μιναρέ του, τα λουτρά και το μαυσωλείο.

Το 1964, το ανάκτορο ανακηρύχθηκε μουσείο-μνημείο και τέθηκε υπό κρατική προστασία.

Το 2000 ανακηρύχθηκε μνημείο παγκόσμιας κληρονομιάς από τη UNESCO μαζί με την παλιά πόλη του Μπακού και τον Παρθένο Πύργο.

Παρά το γεγονός ότι το συγκρότημα κατασκευάστηκε σε διαφορετικές χρονικές περιόδους, το συγκρότημα δίνει ομοιόμορφη εντύπωση, βασισμένη στην αρχιτεκτονικό σχολή του Σιρβάν-Αμπσερόν.

Με τη δημιουργία κυβικών και με πολλές προσόψεις αρχιτεκτονικών όγκων, οι τοίχοι είναι διακοσμημένοι με ανάγλυφα μοτίβα.

Κάθε αρχιτέκτονας, εξαιτίας των παραδόσεων και της αισθητικής που χρησιμοποιήθηκε από τους προκατόχους του, τον ανέπτυξε και τον εμπλούτισε δημιουργικά, με αποτέλεσμα τα επιμέρους κτίσματα να έχουν δημιουργούν την αίσθηση της ενότητας, ρυθμού και αναλογίας των βασικών αρχιτεκτονικών μορφών, δηλαδή του κυβικού όγκου των κτιρίων, των θόλων και των πυλών.

Με την κατάκτηση του Μπακού από τους Σαφαβίδες το 1501, το παλάτι λεηλατήθηκε.

Όλοι οι θησαυροί των Σιρβανσάχ, όπλα, πανοπλίες, κοσμήματα, χαλιά, μπροκάρ, σπάνια βιβλία από τη βιβλιοθήκης του παλατιού, πιάτα από ασήμι και χρυσό, μεταφέρθηκαν από τους Σαφαβίδες στη Ταμπρίζ.

Αλλά μετά την μάχη του Τσαλντιράν το 1514 μεταξύ του στρατού του σουλτάνου της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας Σελίμ Α΄ και τους Σαφαβίδες, η οποία έληξε με ήττα των δεύτερων, οι Τούρκοι πήραν τον θησαυρό των Σιρβανσάχ ως λάφυρα.

Σήμερα βρίσκονται στις συλλογές μουσείων της Τουρκίας, του Ιράν, της Βρετανίας, της Γαλλίας, της Ρωσίας, της Ουγγαρίας.

Μερικά χαλιά του ανακτόρου φυλάσσονται στο μουσείο Βικτώριας και Αλβέρτου του Λονδίνου και τα αρχαία βιβλία φυλάσσονται σε αποθετήρια βιβλίων στην Τεχεράνη, το Βατικανό και την Αγία Πετρούπολη.

========================

Διαβάστε:

The Shirvanshah Palace

The Splendor of the Middle Ages

No tour of Baku’s Ichari Shahar (Inner City) would be complete without a stop at the 15th-century Shirvanshah complex. The Shirvanshahs ruled the state of Shirvan in northern Azerbaijan from the 6th to the 16th centuries. Their attention first shifted to Baku in the 12th century, when Shirvanshah Manuchehr III ordered that the city be surrounded with walls. In 1191, after a devastating earthquake destroyed the capital city of Shamakhi, the residence of the Shirvanshahs was moved to Baku, and the foundation of the Shirvanshah complex was laid. This complex, built on the highest point of Ichari Shahar, remains as one of the most striking monuments of medieval Azerbaijani architecture.

Το Ντιβάν-χανέ

Much of the construction was done in the 15th century, during the reign of Khalilullah I and his son Farrukh Yassar in 1435-1442.

An Egyptian historian named as-Suyuti described the father in superlative terms: “He was the most honored among rulers, the most pious, worthy and just. He was the last of the great Muslim rulers. He ruled the Shirvan and Shamakhi kingdoms for 50 years. He died in 1465, when he was about 100 years old, but he had good eyes and excellent health.”

The buildings that belong to the complex include what may have been living quarters, a mosque, the octagonal-shaped Divankhana (Royal Assembly), a tomb for royal family members, the mausoleum of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi (a famous astronomer of the time) and a bathhouse.

All of these buildings except for the living premises and bathhouse are fairly well preserved. The Shirvanshah complex itself is currently under reconstruction. It has 27 rooms on the first floor and 25 on the second.

Like so many other old buildings in Baku, the real function of the Shirvanshah complex is still under investigation. Though commonly described as a palace, some experts question this. The complex simply doesn’t have the royal grandeur and huge spaces normally associated with a palace; for instance, there are no grand entrances for receiving guests or huge royal bedrooms. Most of the rooms seem more suitable for small offices or monks’ living quarters.

Divankhana

This unique building, located on the upper level of the grounds, takes on the shape of an octagonal pavilion. The filigree portal entrance is elaborately worked in limestone.

The central inscription with the date of the Assembly’s construction and the name of the architect may have been removed after Shah Ismayil Khatai (famous king from Southern Azerbaijan) conquered Baku in 1501.

However, there are two very interesting hexagonal medallions on either side of the entrance. Each consists of six rhombuses with very unusual patterns carved in stone. Each elaborate design includes the fundamental tenets of the Shiite faith: “There is no other God but God. Mohammad is his prophet. Ali is the head of the believers.” In several rhombuses, the word “Allah” (God) is hewn in reverse so that it can be read in a mirror. It seems looking-glass reflection carvings were quite common in the Oriental world at that time.

Scholars believe that the Divankhana was a mausoleum meant for, or perhaps even used for, Khalilullah I. Its rotunda resembles those found in the mausoleums of Bayandur and Mama-Khatun in Turkey. Also, the small room that precedes the main octagonal hall is a common feature in mausoleums of Shirvan.

The Royal Tomb

This building is located in the lower level of the grounds and is known as the Turba (burial vault). An inscription dates the vault to 1435-1436 and says that Khalilullah I built it for his mother Bika khanim and his son Farrukh Yamin. His mother died in 1435 and his son died in 1442, at the age of seven. Ten more tombs were discovered later on; these may have belonged to other members of the Shah’s family, including two more sons who died during his own lifetime.

The entrance to the tomb is decorated with stalactite carvings in limestone. One of the most interesting features of this portal is the two drop-shaped medallions on either side of the Koranic inscription. At first, they seem to be only decorative.

The Turba is one of the few areas in the Shirvanshah complex where we actually know the name of the architect who built the structure. In the portal of the burial vault, the name “Me’mar (architect) Ali” is carved into the design, but in reverse, as if reflected in a mirror.

Some scholars suggest that if the Shah had discovered that his architect inscribed his own name in a higher position than the Shah’s, he would have been severely punished. The mirror effect was introduced so that he could leave his name for posterity.

Remnants of History

Another important section of the grounds is the mosque. According to complicated inscriptions on its minaret, Khalilullah I ordered its construction in 1441. This minaret is 22 meters in height (approximately 66 feet). Key Gubad Mosque, which is just a few meters outside the complex, was built in the 13th century. It was destroyed in 1918 in a fire; only the bases of its walls and columns remain. Nearby is the 15th-century Mausoleum, which is said to be the burial place of court astronomer Seyid Yahya Bakuvi.

Murad’s Gate was a later addition to the complex. An inscription on the gate tells that it was built by a Baku citizen named Baba Rajab during the rule of Turkish sultan Murad III in 1586. It apparently served as a gateway to a building, but it is not known what kind of building it was or even if it ever existed.

In the 19th century, the complex was used as an arms depot. Walls were added around its perimeter, with narrow slits hewn out of the rock so that weapons could be fired from them. These anachronistic details don’t bear much connection to the Shirvanshahs, but they do hint at how the buildings have managed to survive the political vicissitudes brought on by history.

Visitors to the Shirvanshah complex can also see some of the carved stones from the friezes that were brought up from the ruined Sabayil fortress that lies submerged underwater off Baku’s shore. The stones, which now rest in the courtyard, have carved writing that records the genealogy of the Shirvanshahs.

The complex was designated as a historical site in 1920, and reconstruction has continued off and on ever since that time. According to Sevda Dadashova, Director, restoration is currently progressing, though much slower than desired because of a lack of funding.

https://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/82_folder/82_articles/82_shirvanshah.html

========================

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs

by Kamil Ibrahimov

Baku’s Old City is a treasure trove of Azerbaijani history. Its stone buildings and mazy streets hold secrets that have still to be discovered. A masterpiece of Old City architecture, rich in history but with questions still unanswered, is the medieval residence of the rulers of Shirvan, the Shirvanshahs´ Palace.

The State of Shirvan

The state of Shirvan was formed in 861 and became the longest-surviving state in northern Azerbaijan. The first dynasty of the state of Shirvan was the Mazyadi dynasty (861-1027), founded by Mahammad ibn Yezid, an Arab vicegerent who lived in Shamakhi.

In the 10th century, the Shirvanshahs took Derbent, now in the Russian Federation. Under the Mazyadis, the state of the Shirvanshahs stretched from Derbent to the Kur River. The capital of this state was the town of Shamakhi.

In the first half of the 11th century, the Mazyadi dynasty was replaced by the Kasrani dynasty (1028-1382). The state of Shirvan flourished under the Shirvanshahs, Manuchehr III and his son Akhsitan. The last ruler in this dynasty was Hushang. His reign was unpopular and Hushang was killed in a rebellion.

The Kasrani dynasty was later replaced by the Derbendi dynasty (1382-1538), founded by Ibrahim I (1382-1417). Ibrahim I was a well-known but bankrupt feudal ruler from Shaki. His ancestors had been rulers in Derbent, hence the dynasty´s name. Ibrahim was a wise and peace-loving ruler and for some time managed to protect Shirvan from invasion.

To prevent the country´s destruction by Timur (Tamerlane), Ibrahim I took gifts to Timur´s headquarters and obtained internal independence for Shirvan. Ibrahim I failed to unite all Azerbaijani lands under his rule, but he did manage to make Shirvan a strong and independent state.

Baku becomes capital of Shirvan

The 15th century was a period of economic and cultural revival for Shirvan. Since this was a time of peace in Shirvan, major progress was made in the arts, architecture and trade. Shamakhi remained the capital of Shirvan at the start of the century, but an earthquake and constant attacks by the Kipchaks, a Turkic people, led the capital to be moved to Baku.

The city of Baku was the capital of the country during the rule of the Shirvanshahs Khalilullah I (1417-62) and his son Farrukh Yasar (1462-1500).

While tension continued in Shamakhi, Baku developed in a relatively quiet environment. It is known that strong fortress walls were built in Baku as early as the 12th century. After the capital was moved to Baku, the Palace of the Shirvanshahs was erected at the highest point of the city, in what had been one of the most densely populated areas. The palace complex consists of nine buildings – the palace itself, the Courtroom, the Dervish´s Tomb, the Eastern Gate, the Shah Mosque, the Keygubad Mosque, the palace tomb, the bathhouse and the reservoir.

The buildings of the complex are located in three courtyards that are on different levels, 5.6 metres above one another. Since the palace is built on uneven ground, it does not have an orderly architectural plan. The entire complex is constructed from limestone. Of all the buildings, the palace itself has suffered the most wear and tear over the years. The palace was looted in 1500 after Farrukh Yasar was killed in fighting between the Shirvanshahs and the Safavids. As the Iranian and Ottoman empires vied for power in the South Caucasus, the state of Shirvan, on the crossing-point of various caravan routes, suffered frequent attacks. Consequently, the palace was badly damaged many times. Proof of this is the Murad Gate which was built during Ottoman rule.

What is now Azerbaijan was occupied by Russia on 10 February 1828. The Shirvanshahs´ Palace became the Russian military headquarters and many palace buildings were destroyed. In 1954, the Complex of the Palace of the Shirvanshahs was made a State Historic-Architectural Reserve and Museum. In 1960, the authorities of the Soviet republic decided to promote the palace as an architectural monument.

The Palace Building

The palace is a two-storey building in an irregular, rectangular shape. In order to provide better illumination of the palace, the south-eastern part of the building was constructed on different levels. Initially there were 52 rooms in the palace, of which 27 were on the ground floor and 25 on the first floor. The shah and his family lived on the upper floor, while servants and others lived on the lower floor.

The Tomb Built by Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar (also known as the Courtroom or Divankhana)

Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar had the tomb constructed in the upper courtyard of the palace complex. Its north side and one of its corners adjoin the residential building. The tomb consists of an octagonal rotunda, completed with a dodecagonal dome. Its octagonal hall is surrounded by an open balcony or portico. The balcony is edged with nine columns which still have their original capitals. The rotunda stands in a small courtyard which also has an open balcony running around its edge. The balcony´s columns and arches are the same shape as those of the rotunda. The outer side of the columns has a stone with the image of a dove, the symbol of freedom, and two stone chutes to drain water away. Some researchers believe that this building was used for official receptions and trials and call it the Courtroom. The architectural work in the tomb was not completed. The tomb is considered one of the finest examples of medieval architecture, not only in Azerbaijan but in the whole Middle East.

The Dervish´s Tomb

The Dervish´s Tomb is located in the southern part of the middle courtyard. Some historians maintain that it is the tomb of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi, who was a royal scholar and astronomer under Khalilullah I.

Other historians say that all the buildings in the lower courtyard of the palace, including the Dervish´s Tomb, are part of a complex where dervishes lived, but there is little evidence for this.

The Keygubad Mosque

Now in ruins, the Keygubad Mosque was a mosque-cum-madrasah joined to the Dervish´s Tomb.

The tomb was located in the southern part of the mosque.

The mosque consisted of a rectangular prayer hall and a small corridor in front of it. In the centre of the hall four columns supported the dome.

Historian Abbasgulu Bakikhanov wrote that Bakuvi taught and prayed in the mosque: “The cell where he prayed, the school where he worked and his grave are there, in the mosque”.

Keygubad Shirvanshah ruled from 1317 to 1343 and was Sheikh Ibrahim´s grandfather.

The Eastern Gate

The Eastern or Murad Gate is the only part of the complex that dates to the 16th century. Two medallions on the upper frame of the Murad Gate bear the inscription: “This building was constructed under the great and just Sultan Murad III on the basis of an order by Racab Bakuvi in 994” (1585-86).

The Tomb of the Shirvanshahs

There are two buildings in the lower courtyard – the tomb and the Shah Mosque. A round wall encloses the lower courtyard, separating it from the other yards. When you look at the tomb from above, you can see that it is rectangular in shape, decorated with an engraved star and completed with an octagonal dome. While the tomb was being built, blue glazed tiles were placed in the star-shaped mortises on the dome.

An inscription at the entrance says: “Protector of the religion, man of the prophet, the great Sultan Shirvanshah Khalilullah, may God make his reign as shah permanent, ordered the building of this light tomb for his mother and seven-year-old son (may they rest in peace) 839” (1435-36). The architect´s name is also inscribed between the words “God” and “Mohammad” on another decorative inscription on the portal which can be read only using a mirror. The inscription says “God, architect Ali, Mohammad”.

A skeleton 2.1 metres tall was found opposite the entrance to the tomb. This is believed to be Khalilullah I´s own grave. A comb, a gold earring and other items of archaeological interest were found there.

The Shah Mosque

The Shah Mosque is in the lower courtyard, alongside the mausoleum. The mosque is 22 metres high. An inscription around the minaret says: “The Great Sultan Khalilullah I ordered the erection of this minaret. May God prolong his rule as Shah. Year 845” (1441-42).

Stairs lead from a hollow in the wall behind the minbar or pulpit to another small room. Stone traceries on the windows decorate the mosque.

The Palace Bathhouse

The palace bathhouse is located in the lowest courtyard of the complex. Like all bathhouses in the Old City, this one was built underground to ensure that the temperature inside was kept stable. As time passed the level of the earth rose and covered it completely. The bathhouse was found by chance in 1939. In 1953 part of it was cleaned and in 1961 restoration work was done and the dome repaired. The walls in one of the side rooms are covered with glazed tiles and this room is thought to have been the shah´s room.

Cistern

The cistern, part of an underground water distribution system, was constructed in the lower part of the bathhouse to supply the Shirvanshahs´ Palace with water. Water came into the cistern via ceramic pipes which were part of the Shah´s Water Pipeline, laid from a high part of the city. The cistern is located underground and its entrance has the shape of a portal. Numerous stairs lead from the entrance down to the storage facility. A link between the cistern and the bathhouse can be seen from the side lobby. The cistern was found by chance during restoration work in 1954.

Literature

S.B. Ashurbayli: Государство Ширваншахов (The State of the Shirvanshahs), Baku, Elm, 1983; and Bakı şəhərinin tarixi (The History of the City of Baku), Baku, Azarnashr, 1998

F.A. Ibrahimov and K.F. Ibrahimov: Bakı İçərişəhər (Baku Inner City), Baku, OKA, Ofset, 2002. Kamil Farhadoghlu: Bakı İçərişəhər (Baku Inner City), Sh-Q, 2006; and Baku´s Secrets are Revealed (Bakının sirləri açılır), Baku, 2008

E.A. Pakhomov: Отчет о работах по шахскому дворцу в Баку (Report on Work in the Shah´s Palace in Baku), News of the AAK, Issue II, Baku, 1926; and Первоначальная очистка шахского дворца в Баку (Initial Clearing of the Shah´s Palace in Baku), News of the AAK, Issue II, Baku, 1926

Chingiz Gajar: Старый Баку (Old Baku), OKA, Ofset, 2007

M. Huseynov, L. Bretanitsky, A. Salamzadeh, История архитектуры Азербайджана (History of the Architecture of Azerbaijan). Moscow, 1963

M.S. Neymat, Корпус эпиграфических памятников Азербайджана (Azerbaijan´s Epigraphic Monuments), Baku, Elm, 1991

A.A. Alasgarzadah, Надписи архитектурных памятников Азербайджана эпохи Низами (Inscriptions on the architectural monuments of Azerbaijan from the era of Nizami) in the collection, Архитектура Азербайджана эпохи Низами (Azerbaijan in the Era of Nizami), Moscow, 1947.

http://www.visions.az/en/news/159/cdc770e3/

=============================

Šervānšāhs

Šervānšāhs (Šarvānšāhs), the various lines of rulers, originally Arab in ethnos but speedily Persianized within their culturally Persian environment, who ruled in the eastern Caucasian region of Šervān from mid-ʿAbbasid times until the age of the Safavids.

The title itself probably dates back to pre-Islamic times, since Ebn Ḵordāḏbeh, (pp. 17-18) mentions the Shah as one of the local rulers given his title by the Sasanid founder Ardašir I, son of Pāpak. Balāḏori (Fotuḥ, pp. 196, 203-04) records that the first Arab raiders into the eastern Caucasus in ʿOṯmān’s caliphate encountered, amongst local potentates, the shahs of Šarvān and Layzān, these rulers submitting at this time to the commander Salmān b. Rabiʿa Bāheli.

The caliph Manṣur’s governor of Azerbaijan and northwestern Persia, Yazid b. Osayd Solami, took possession of the naphtha wells (naffāṭa) and salt pans (mallāḥāt) of eastern Šervān; the naphtha workings must mark the beginnings of what has become in modern times the vast Baku oilfield.

By the end of this 8th century, Šervān came within the extensive governorship, comprising Azerbaijan, Arrān, Armenia and the eastern Caucasus, granted by Hārun-al-Rašid in 183/799 to the Arab commander Yazid b. Mazyad, and this marks the beginning of the line of Yazidi Šervānšāhs which was to endure until Timurid times and the end of the 14th century (see Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-42 n. 67).

Most of what we know about the earlier centuries of their power derives from a lost Arabic Taʾriḵ Bāb al-abwāb preserved within an Arabic general history, the Jāmeʿ al-dowal, written by the 17th century Ottoman historian Monajjem-bāši, who states that the history went up to c. 500/1106 (Minorsky 1958, p. 41). It was exhaustively studied, translated and explained by V. Minorsky (Minorsky, 1958; Ḥodud al-ʿālam, commentary pp. 403-11); without this, the history of this peripheral part of the mediaeval Islamic world would be even darker than it is.

The history of Šervānšāhs was clearly closely bound up with that of another Arab military family, the Hāšemis of Bāb al-abwāb/Darband (see on them Bosworth, 1996, pp. 143-44 n. 68), with the Šervānšāhs at times ruling in the latter town (at times invited into Darband by rebellious elements there, see Minorsky 1958, pp. 27, 29-30), and there was frequent intermarriage between the two families.

By the later 10th century, the Shahs had expanded from their capital of Šammāḵiya/Yazidiya to north of the Kura valley and had absorbed the petty principalities of Layzān and Ḵorsān, taking over the titles of their rulers (see Ḥodud al-ʿālam, tr. Minorsky, pp. 144-45, comm. pp. 403-11), and from the time of Yazid b. Aḥmad (r. 381-418/991-1028) we have a fairly complete set of coins issued by the Shahs (see Kouymjian, pp. 136-242; Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41).

Just as an originally Arab family like the Rawwādids in Azerbaijan became Kurdicized from their Kurdish milieu, so the Šervānšāhs clearly became gradually Persianized, probably helped by intermarriage with the local families of eastern Transcaucasia; from the time of Manučehr b. Yazid (r. 418-25/1028-34), their names became almost entirely Persian rather than Arabic, with favored names from the heroic national Iranian past and with claims made to descent from such figures as Bahrām Gur (see Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41).

The anonymous local history details frequent warfare of the Shahs with the infidel peoples of the central Caucasus, such as the Alans, and the people of Sarir (i.e. Daghestan), and with the Christian Georgians and Abḵāz to their west. In 421/1030 Rus from the Caspian landed near Baku, defeated in battle the Shah Manučehr b. Yazid and penetrated into Arrān, sacking Baylaqān before departing for Rum, i.e. the Byzantine lands (Minorsky, 1958, pp. 31-32). Soon afterwards, eastern Transcaucasia became exposed to raids through northern Persia of the Turkish Oghuz. Already in c. 437/1045, the Shah Qobāḏ b. Yazid had to built a strong stone wall, with iron gates, round his capital Yazidiya for fear of the Oghuz (Minorsky 1958, p. 33). In 458-59/1066-67 the Turkish commander Qarategin twice invaded Šervān, attacking Yazidiya and Baku and devastating the countryside.

Then after his Georgian campaign of 460/1058 Alp Arslan himself was in nearby Arrān, and the Shah Fariborz b. Sallār had to submit to the Saljuq sultan and pay a large annual tribute of 70,000 dinars, eventually reduced to 40,000 dinars; coins issued soon after this by Fariborz acknowledge the ʿAbbasid caliph and then Sultan Malekšāh as his suzerain (Minorsky 1958, pp. 35-38, 68; Kouymjian, pp. 146ff, who surmises that, since we have no evidence for the minting of gold coins in Azerbaijan and the Caucasus at this time, Fariborz must have paid the tribute in Byzantine or Saljuq coins).

Fariborz’s diplomatic and military skills thus preserved much of his family’s power, but after his death in c. 487/1094 there seem to have been succession disputes and uncertainty (the information of the Taʾriḵ Bāb al-abwāb dries up after Fariborz’s death).

In the time of the Saljuq sultan Maḥmud b. Moḥammad (r. 511-25/1118-31), Šervān was again occupied by Saljuq troops, and the disturbed situation there encouraged invasions of Šammāḵa and Darband by the Georgians. During the middle years of the 12th century, Šervān was virtually a protectorate of Christian Georgia. There were marriage alliances between the Shahs and the Bagratid monarchs, who at times even assumed the title of Šervānšāh for themselves; and the regions of Šakki, Qabala and Muqān came for a time directly under Georgian rule (Nasawi, text, pp. 146, 174). The energies of the Yazidi Shahs had to be directed eastwards towards the Caspian, and on various occasions they expanded as far as Darband.

The names and the genealogical connections of the later Šervānšāhs now become very confused and uncertain, and Monajjem-bāši gives only a skeletal list of them from Manučehr (III) b. Faridun (I) onwards. He calls this Shah Manučehr b. Kasrān, and the names Kasrānids or Ḵāqānids appear in some sources for the later shahs of the Yazidi line in Šervān (Minorsky, 1958, pp. 129-38; Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41). Manučehr (III) not only called himself Šervānšāh but also Ḵāqān-e Kabir “Great Khan,” and it was from this that the poet Ḵāqāni, a native of Šervān and in his early years eulogist of Manučehr, derived his taḵalloṣ or nom-de-plume. Much of the line of succession of the Shahs at this time has to be reconstructed from coins, and from these the Shahs of the 12th century appear as Saljuq vassals right up to the time of the last Sultan, Ṭoḡrïl (III) b. Arslān, after which the name of the caliphs alone appear on their coins (Kouymjian, pp. 153ff, 238-42).

In the 13th century, Šervān fell under the control first of the Khwarazmshah Jalāl-al-Din Mengüberti after the latter appeared in Azerbaijan; according to Nasawi (p. 75), in 622/1225 Jalāl-al-Din demanded as tribute from the Šervānšāh Garšāsp (I) b. Farroḵzād (I) (r. after 600/1204 to c. 622/1225) the 70,000 dinars (100,000 dinars?) that the Saljuq sultan Malekšāh had exacted a century or more previously (see Kouymjian, pp. 152-53). Shortly afterwards, Šervān was taken over by the Mongols, and at times came within the lands of the Il-Khanids and at others within the lands of the Golden Horde.

At the outset, coins were minted there in the name of the Mongol Great Khans, with the names of the Kasrānid Shahs but without their title of Šervānšāh, but then under the Il-Khanids, no coins were struck in Šervān. The Kasrānids survived as tributaries of the Mongols, and the names of Shahs are fragmentarily known up to that of Hušang b. Kayqobāḏ (r. in the 780s/1370s; see Bosworth, 1996, p. 141; Barthold and Bosworth, 1997, p. 489).

This marked the end of the Yazidi/Kasrānid Shahs, but after their disappearance there came to power in Šervān a remote connection of theirs, Ebrāhim b. Moḥammad of Darband (780-821/1378-1418). He founded a second line of Shahs, at first as a tributary of Timur but latterly as an independent ruler, and his family was to endure for over two centuries.

The 15th century was one of peace and prosperity for Šervān, with many fine buildings erected in Šammāḵa/Šemāḵa and Baku (see Blair, pp. 155-57), but later in the century the Shahs’ rule was threatened by the rise of the expanding and aggressive shaikhs of the Ṣafavi order; both Shaikh Jonayd b. Ebrāhim and his son Ḥaydar were killed in attempted invasions of Šervān and the Darband region (864/1460 and 893/1488 respectively).

Once established in power in Persia, Shah Esmāʿil I avenged these deaths by an invasion of Šervān in 906/1500, in which he killed the Šervānšāh Farroḵ-siār b. Ḵalil (r. 867-905/1463-1500), then reducing the region to dependent status (see Roemer, pp. 211-12).

The Shahs remained as tributaries, and continued to mint their own coins, until in 945/1538 Ṭahmāsp I’s troops invaded Šervān, toppled Šāhroḵ b. Farroḵ, and made the region a mere governorship of the Safavid empire.

In the latter half of the 16th century, descendants of the last Shahs endeavored, with Ottoman Turkish help, to re-establish their power there, and in the peace treaty signed at Istanbul in 998/1590 between the sultan Morād III and Shah ʿAbbās I, Šervān was ceded to the Ottomans; but after 1016/1607 Safavid authority was re-imposed and henceforth became permanent till the appearance of Russia in the region in the 18th century (see Roemer, pp. 266, 268; Barthold and Bosworth, 1997, p. 489).

Την αναφερόμενη βιβλιογραφία θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/servansahs

==========================

Šervān (Širvān, Šarvān)

Šervān (Širvān, Šarvān), a region of Eastern Transcaucasia, known by this name in both early Islamic and more recent times, and now (since 1994) substantially within the independent Azerbaijan Republic, being bounded by the Islamic Republic of Iran on the south, the independent Armenian Republic on the west, and Daghestan of the Russian Federation of States on its north.

Geography and topography

Šervān proper comprised during the early Islamic centuries, as its northern part, the south-easternmost spurs of the main Caucasus range (which here rises to 4,480 m/13,655 ft), and then as its southern part the lower lands sloping down to the course of the Korr/Kura river, this last in its lower reaches below sea level. Hence to the south of this river boundary and of its confluent the Aras or Araxes, lay the region of Muqān, whilst to the northwest of Šervān lay the region of Šakki (q.v.) and to its west that of Arrān (see the maps in Minorsky, 1953, p. 78, and idem, 1958, p. 174).

However, throughout much of its history, the rulers of Šervān, and especially the Šervānšāhs who ruled from the beginning of the 9th century to the beginning of the 17th century, strove to extend their boundaries northwards into the mountain region of Layzān, and eastwards to the Caspian shores, to Qoba and to Masqat or Maškat in the direction of Bāb al-abwāb or Derbend and further southwards to Baku.

The lowland regions of Šervān were exposed to pressure from powerful neighbors like the Alans or Ossets of the central Caucasus, the Hashimid rulers of Bāb al-abwāb, the predatory Rus from the Caspian waters, and Kurdish and Daylami powers to the south like the Šaddādids and Mosāferids (qq.v.).

The towns of Šarvān included Šāvarān/Šābarān, the ancient center of the southern Qoba district, but above all, Šammāḵa or Šammāḵiya, which is said to have been named after an Arab governor of the region, Šammāḵ b. Šojāʿ, a subordinate of the governor of Azerbaijan, Arrān and Armenia for Hārun-al-Rašid, Saʿid b. Salm b. Qotayba Bāheli (see Balāḏori, Fotuḥ, p. 210).

Soon afterwards it became the capital for the founder of the line of Yazidi Šervānšāhs, Yazid b. Mazyad Šaybāni (d. 185/201), and is described by the 10th century Arab geographers as a town built of stone in the midst of a fertile, corn-growing region (see Le Strange, Lands, pp. 179-80).

In 306/918 it was apparently temporarily renamed Yazidiya, but it has been the old name that has survived (cf. Yāqut, Boldān [Beirut] III, p. 361; V, p. 436), and at the present time Shemakha is the administrative centre of this district of the Azerbaijan Republic.

History

With the decline of the Safavids in the early 18th century, Šervān again came under Ottoman rule, but Peter the Great’s expansionist policies were now a new factor, as Russian ambitions in Eastern Caucasia became apparent.

By the Russo-Turkish treaty of 1724 the coastal region of Baku was for the first time severed from inland Šervān, which was left to the Turkish governor in Šemāḵa (see Shaw, pp. 299-300).

This arrangement was held firm after Persian control was reasserted by Nāder Shah, who captured Šemāḵa in 1734, and by the Russo-Persian Treaty of Ganja of 1735, Nāder’s control over Darband, Baku, and the coastal lands was conceded by the Empress Catherine I (see Kazemzadeh, pp. 323-24).

However, Persian influence in the eastern Caucasus receded after Nāder’s death in 1160/1747, and various local princes took power there, including in Šervān and Darband.

Russian pressure increased towards the end of the 18th century. Moṣṭafā Khan of Šervān submitted to Tsar Alexander I in 1805, whilst still continuing secretly to seek Persian aid, and in 1806 the Russians occupied Darband and Baku.

The Golestān Treaty of 1813 between Russia and Persia definitively allocated Darband, Qoba, Šervān. and Baku to the Tsar (Kazemzadeh, p. 334). In 1820 Russian troops occupied Šemāḵa, Moṣṭafā Khan despairingly fled to Persia, and Šervān was definitively incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Under Tsarist rule, Šervān and Šemāḵa came within various administrative divisions of the empire.

Many of the older Islamic buildings of the city were damaged in an earthquake of 1859, but as late as this time, Šemāḵa still had a larger population (21,550) than Baku (10,000), before the latter’s demographic and industrial explosion as a centre of oil exploitation over the next two or three decades.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, these regions came within the nominally Soviet Azerbaijan, with Šemāḵa becoming the centre of a raǐon or administrative district, though its estimated population of 17,900 in 1970 was still well below the 19th century level. (See also Barthold and Bosworth).

Την αναφερόμενη βιβλιογραφία θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/servan

==============================

Περισσότερα:

https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ανάκτορο_των_Σιρβανσάχ

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Дворец_ширваншахов

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_of_the_Shirvanshahs

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Государство_Ширваншахов

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shirvan

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ширван

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shirvanshah

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ширваншах

https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Σιρβανσάχ

============================

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/ss-250734946

https://issuu.com/megalommatis/docs/the_shahs_of_shirvan_and_their_palace_at_baku.docx

https://vk.com/doc429864789_622142368

https://www.docdroid.net/bEG3d9g/oi-sakhides-toy-sirvan-sirvan-sakh-kai-to-anaktoro-toys-sto-mpakou-docx

A depiction of iconoclasm, from a 9th-century psalter. The iconoclasts believed that praying to works of religious art was tantamount to idolatry. Several Byzantine rulers encouraged the destruction of religious icons, which helped to widen the gap between Byzantine Christians and the Popes.

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

The Spiritual Potency of Simple People: from J. B. Duroselle to today's Manichaean Rulers of Europe to a Crushed Greek Antichrist

Few days ago, an Egyptian friend wrote to me and commented on my article 'Plea for Jean Baptiste Duroselle’s Brilliant Book, Europe: A History of its Peoples':

Table of Contents

I. How Simple People can utterly destroy today's World

II. Jean Baptiste Duroselle and Yahya Ibn Zakariya

III. Lassalian Monks and Schools

IV. Western European Elites hide their Manichaean Nature and Evil Faith

V. "Gods" do not accept Multipolar Worlds!

VI. A Greek World Leader and False Messiah: One of the several Antichrists to come

VII. The Duroselle Affair in Greece, and I

I. How Simple People can utterly destroy today's World

His pessimistic viewpoint forced me to write a rather long response, because it is an essential issue of Moral and a supreme moral obligation for anyone not to associate himself with the injustice and the lawlessness of today's world, and even more so, to do all that it takes to dissociate himself from the surrounding environment, to reject it and to denounce it as inhuman, impermissible and subject to monstrous, terminal annihilation.

It is only due to the prevailing worldwide, overwhelming and compact materialism, evolutionism and relativism that people lost their faith and cannot duly assess the eventually great spiritual power of the wish and of the negative wish. A faithless person that does not truly believe in the spiritual world cannot bring forth results in either wishes or negative wishes; I have to point out that I fully distinguish between negative wish and curse. In the latter case, one person invokes something harmful to someone, whereas in the former case, one demands forcefully that a negative development be averted or cancelled. Although a curse may be at times morally imposed to be uttered, a negative wish is essential to be thunderously expressed every time one person encounters a case of injustice, a wrongdoing, evilness, and any sort of falsehood, deceit, perfidy, scheme, chicanery or lie.

Today's faithless Muslims, Christians, Confucians, Taoists, Hindus, Buddhists and others have lost real faith in the spiritual, 'supernatural', world. They stupidly believe only in diverse stories and unimportant narratives, which -in spite of their possible veracity- do not constitute an inherent part of the true religion; their faith to God is only nominal. The ensuing catastrophic consequences lead to indiscriminate feelings of inefficiency, impotency and, even worse, self-depreciation. Due to this situation, they become effectively irreligious, because they practice their religion only mechanically (imitating ancestors) or hypocritically (to show to the society that they are faithful); but this is utter disbelief. What follows this encumbering situation is spiritual apathy; this involves also emotional indifference, and full purposelessness in life. These people are characterized by moral depravity indeed, not in the sense of being genuinely corrupt, but for not reacting, for keeping silent, and for tolerating the wrongdoing.

A positive wish can do wonders for many; and a negative wish has the power to prevent many evil acts and ominous developments from happening. Virtually any taciturn or vociferous person, who has strong faith, can express formidable negative wishes and bring forth results. This actually happens, but today's idiotic materialists simply cannot 'see' or understand it. A very well focalized negative wish cancels everything; from a simple governmental act to an assassination attempt to a war. And I can conclude that the chaotic situation in which all the powerful and evil lobbies of today's world find themselves, failing to achieve what they intend, has much to do with highly synchronized negative wishes that resolutely cancel the Satanic plans of all the 'Christian', 'Jewish', 'Muslim', 'Hindu', 'Buddhist', 'Taoist', 'Confucian', 'Shinto' or other governments, which sooner or later will disappear in utmost ruination.

In fact, all the forthcoming disasters come -also- from the negative wishes expressed in our world by people who -thanks to their moral standards and irrespective of their religion- fully understand that this world is impermissible to exist and has therefore to vanish in monstrous extermination. All negative wishes expressed against today's lawless world are the path of the few to the Paradise; and every sort of reluctance, every form of indifference, and every aspect of apathy toward today's criminal governments, Satanic presidents, demonic prime ministers, and other anomalous magistrates open the Gates of the Hell to all the idiots who think that Eternal Life can possibly hinge on meaningless cults hypocritically performed just to ensure later 'reward'.

Quite unfortunately for the present, diabolical but perishing world's establishment, God is not as malleable and as stupid as they delusionally imagine He is; and I am not referring to the 'Demiurge'….

You can herewith find my friend's comment and my lengthy response.

-- A friend's comment about my Plea for J. B. Duroselle’s Book --

Very interesting story about this guy Jean Baptiste! His name reminded me of my college: College St. Jean Baptiste De La Salle in Bab El Louk, then Khoronfich, then in Daher...

This shows how Europeans are like the other crooks, how they plan things in advance, and they pass them on.

What do we have in our hands to change things, except to write and express our views, without any results…

-------------------- My response ------------------

Dear Awadallah,

Thank you for your response, which so well shows that you understand that the Jean Baptiste Duroselle affair (in Greece 1990-1991), although it looks like an ‘internal’ European story (as an indication of the barbaric, ultra-nationalist and paranoid character of the basically uneducated and absolutely uncultured Greek society), has indeed wider implications. That is true.

II. Jean Baptiste Duroselle and Yahya Ibn Zakariya

All neighboring states must demonstrate a particular concern when, in a wretched country, people react with such hysteria, every time the lies that they stupidly believe in are overwhelmingly rejected by the world’s leading scholars.

Your email offered me the chance of a flash back and of a self-reappraisal; I will tell you what I mean.

However, let me start with a funny episode of the Greek, absurd and paranoid, reaction (back in 1990-1991) against Duroselle’s book, which is nowadays the cornerstone of all the EU member states’ secondary education — except for the backward trash of Greece where the education manuals are more racist than those in Nazi Germany at the time of Hitler.

In the fever of the anti-Duroselle madness that turned the average Greeks to rabid dogs back in 1989-1991, every famous person felt stupidly obliged to contribute to that mental and intellectual cholera, to promote the local chauvinism, and to speak against Jean Baptiste Duroselle.