Large - Blog Posts

Beach Style Sunroom

Idea for a sunroom with a large coastal limestone floor and beige floor, no fireplace, and a typical ceiling

AfroSuperHero: Kesiah Jones aka Captain Rugged, occupe les rues de Lagos prêt à défendre le pauvre et l'opprimé.

Musique Kesiah Jones - Illustrations Native Maqari

Participer c'est prendre part, apporter une part et bénéficier, nous dit Joelle Zask dans Participer. C'est la philosophie de Dieuf Dieul - faire et prendre, en wolof- un des groupes qui a fait la musique sénégalaise des années 1970-1980.

Des utopies non alignées

Publié dans le magazine du Goethe Institut RDC

Vu d’Occident il semblerait que le futur devienne une notion obsolète voire une vision inquiétante. Mais sur le continent africain la perspective est tout autre portée par la mondialisation, l’essor des technologies numériques et une jeunesse qui veut croire que de nouvelles perspectives s’ouvrent à elle. Alors qu’une élite entreprenante emboite le pas au modèle techno-capitaliste néolibéral, des voix se font entendre pour imaginer des futurs non alignés sur les modèles de développement occidentaux qui ont largement montré leurs limites.

En Europe le futur serait-il devenu une notion obsolète? Les crises à répétition du capitalisme financier, la menace d’un changement climatique dont les effets destructeurs seraient irrémédiables pour la planète, la multiplication des conflits et les mouvements massifs de population qui en résultent, l’écart croissant séparant les plus riches des plus pauvres, nourrissent le sentiment que ce qui est « à venir » n’est peut-être plus du tout désirable.

Du côté des États-Unis, le futur apparait totalement confisqué par les projections des maîtres de la Silicon Valley. À travers le projet trans-humaniste développé au sein des laboratoires de la Singularity University fondée par le futurologue Ray Kurzweil, les grandes entreprises de la révolution numérique prétendent relancer le progrès grâce principalement aux recherches dans les neurosciences qui pourraient transformer notre humanité. En attendant l’avènement d’un être nouveau issu de l’union de l’homme et de la machine, elles inondent le monde de gadgets technologiques plus futuristes les uns que les autres destinés à remporter notre adhésion.

Mais ces deux visions ne prennent pas en compte les profondes transformations géopolitiques amorcées au siècle dernier qui façonnent les débuts du XXIe siècle. En effet, l’entrée de nouveaux acteurs dans la politique et l’économie mondiales ont provoqué des transferts de pouvoirs et fait émerger des puissances alternatives. De ce monde multipolaire dont l’Occident n’est plus le centre surgissent de nouvelles représentations qui fonctionnent comme autant d’outils collectifs de spéculation et mettent à jour de nouvelles potentialités.

Avec des taux de croissance positifs, des ressources premières stratégiques, un équipement technologique grandissant et une population majoritairement jeune – en 2050 le continent africain comptera 2,4 milliards d’Africains dont près de la moitié aura moins de 18 ans et dont 60 % vivra dans les villes –, l’Afrique dispose d’atouts générateurs d’une dynamique qui fait d’elle le continent du futur. Mais si l’Afrique est le continent du futur, il n’en reste pas moins qu’à l’heure actuelle, un Africain sur deux est encore en situation de grande pauvreté. La conjonction population majoritairement jeune / taux de chômage élevé / urbanisation galopante / incapacité actuelle des gouvernements à satisfaire les besoins en énergies prévaut dans de nombreux pays et est potentiellement explosive. Les très convoités minerais de l’électronique – la cassitérite, le coltan, la wolframite et l’or qui entrent dans la fabrication de la majorité des produits électroniques – sont avant tout des facteurs de conflit. Et depuis quelques années, le continent abrite parmi les plus grandes déchetteries à ciel ouvert de matériel électronique au monde.

Face au grand écart que vit le continent au quotidien, des voix s’élèvent pour défendre l’idée que si l’Afrique veut élaborer des futurs qui lui soient profitables, il lui faut accomplir une profonde révolution culturelle.

C’est ce à quoi s’attachent deux initiatives remarquables, portées d’un côté par un économiste et écrivain sénégalais, Felwine Sarr et de l’autre, par un collectif, le WɔɛLab au Togo.

La démarche de Felwine Sarr développée notamment dans son dernier ouvrage, Afrotopia, se revendique comme une « utopie active » et pourrait peut-être bien devenir le terreau d’un mouvement intellectuel et artistique. Pour l’économiste, ce dont souffre l’Afrique, c’est avant tout d’un déficit « d’une pensée et d’une production de ses propres métaphores du futur ». Pour que le continent puisse « se penser, se représenter, se projeter » Felwine Sarr prône le non alignement sur les modèles de développement tels qu’ils ont été conçus par les puissances occidentales et qui fonctionnent pour l’Afrique comme l’objectif à atteindre quelqu’en soit le coût humain, culturel et social. C’est en opérant la rupture et en procédant à une archéologie des cultures locales que le continent africain parviendra à mettre en place des modèles autochtones « plus conscients, plus soucieux de l’équilibre entre les différents ordres, du bien commun et de la dignité ». Au delà, c’est en trouvant sa force propre que l’Afrique pourra contribuer à « porter l’humanité à un autre palier ».

Ouvert en 2012 par l’architecte / anthropologue Sename Koffi Agbodjinou, le WɔɛLab qui se définit comme le premier espace de démocratie technologique est également une utopie active. Ce fablab / hackerspace / incubateur / école, revendique l’action « par la base et pour la base », combat la notion de propriété et a pour ambition de redonner aux citadins une capacité d’action en articulant réapropriation des savoirs vernaculaires, technologies numériques, culture du partage et intelligence collective. Concretement, sa démarche consiste à transposer en milieu urbain des modes de fonctionnement traditionnels qui ont prouvé leur efficacité, comme par exemple les enclos d’initiation (espaces d’apprentissage dans lesquels les jeunes réunis par tranche d’âge sont accompagnés pour détecter leur compétences et les transformer en savoir-faire) à les mettre au service d’innovations technologiques utiles et viables économiquement. Il s'est récemment distingué à l’échelle internationale en concevant la première imprimante 3D quasiment exclusivement à partir de déchets informatiques recyclés.

Ces démarches nous suggèrent que pour penser le futur de l’Afrique il convient donc de se placer dans une perspective plurielle et non alignée, de penser avec les capacités d’anticipation autochtones et contre les rémanences du colonialisme soutenues par la globalisation et son modèle économique « star », l’ultra libéralisme.

Oulimata Gueye

WɔɛLab http://www.woelabo.com/

Felwine Sarr, Afrotopia, Philippe Rey, Paris 2016, 160 pages.

City in the Blue Daylight: @Nataal explores the 16th Dak’art Biennial for Contemporary African Art @biennalededakar

http://bit.ly/Dakart

P A R E N T S ’ T O U C H

Stills from: Boneshaker (2013), Afronauts (2014), Toughlove (unreleased) (all directed by Frances Bodomo & shot by Joshua James Richards)

Ignorance is ignorance, no matter where you find it.

Samuel R. Delany, “The Story of Old Venn” (via wordswilling)

Le savoir est l’unique fortune qu’on peut donner entièrement sans en rien la diminuer. Amadou Hampathe Ba

David Hammons, Untitled (The Embrace), 1975

(A riff on Klimt’s Kiss? or are we hallucinating…)

Glenn Ligon, Give us a Poem (Palindrome #2), 2007

“Glenn Ligon made this neon piece […] in 2007, and I saw it a little while back on the wall of the Studio Museum in Harlem, where it’s part of the permanent collection. The work is built around an incident that occurred at Harvard in 1975, when Muhammad Ali had just finished a speech and a student in the audience asked him to improvise a poem: ‘Me/We’ was the pithy verse Ali offered. Even then, at the height of the Black Power movement, it was an intriguingly opaque statement that could have been read as a gesture of solidarity between the black boxer and his white audience, or as an underlining of their difference. In Ligon’s work, the two words become a visual palindrome, of sorts – symmetrical top and bottom – and alternate being lit (white) and unlit (black), which just increases the tension inherent in them. In 2014, in a museum in Harlem, it strikes me that the tension is between the artist and the audience he addresses – with the issue of race still there, but now wrapped up in larger issues of aesthetic communities and the class, and color, they imply." Blake Gopnik, The Daily Pic

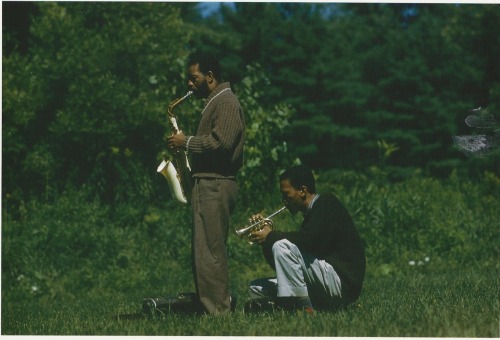

Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry in 1959.

Credit: Lee Friedlander

Moi, Albert Ibokwe Khoza

Johannesburg 31 octobre 2015. Alors que les manifestations étudiantes pour un accès égalitaire à l'enseignement imprègnent encore littéralement l'atmosphère et que #FeesMustFall est devenu le slogan de ralliement de la jeunesse sud-africaine, Albert Ibokwe Khoza incarne un autre combat, étroitement lié en réalité : celui de la place du corps. Acteur, danseur, performer, chanteur et praticien traditionnel (sangoma en Afrique du Sud), Au cœur de Soweto, Albert Ibokwe Khoza nous invite à suivre le trajet qu’il a parcouru des bancs de l’Université du Witwatersrand, à la scène internationale. C’est au cours de ce trajet qu’il réussit à faire de son corps, l’instrument de son émancipation. En rejetant à la fois l’académisme universitaire qui emprisonne son corps dans une discipline qui lui est fondamentalement étrangère et en imposant son homosexualité qui pour beaucoup encore, reste incompatible avec les pratiques traditionnelles.

A closet Chant, Albert Ibokwe Khoza

A noter également une remarquable collaboration car la performance se déroulait dans la galerie de Soweto, Mashumi Art Projects créée par Zanele Mashumi, elle même invitée par l’artiste Thenjiwe Nkosi. Thenjiwe Nkosi qui s’appuit sur le concept de “radical sharing” avait répondu à l’invitation du Goethe pour le festival African futures en invitant quatre autres projets développés par des femmes. Multiplier, le titre de cette collaboration est présenté sur le site du festival. Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

Oulimata Gueye

ICARUS 13

Premier voyage vers le soleil

Kiluanji Kia Henda

Portfolio • La Revue du Crieur

Icarus 13 est un projet de première importance pour l'Afrique. Grâce aux nouvelles technologies et outils ad hoc, nous avons fabriqué un vaisseau spatial qui nous aidera à développer notre savoir, notre créativité et notre imagination. Il a la capacité d'atterrir sur cette gigantesque étoile qu'est le Soleil, à condition de voyager de nuit. Le rêve autrefois formé par Icare est enfin devenu réalité.

Interview of Kenyan film writer/director Wanuri Kahiu, about “Africa and science fiction”, in reference to the sci-fi movie she wrote and directed: Pumzi, 2009

This interview was part of the exhibition “Si ce monde vous déplaît” at the FRAC Lorraine, Metz (France), 2013.

Oulimata Gueye

The Powers of Mourning

"I have tried to suggest that precarity is the condition against which several new social movements struggle. Such movements do not seek to overcome interdependency or even vulnerability as they struggle against precarity; rather, they seek to produce the conditions under which vulnerability and interdependency become liveable. This is a politics in which performative action takes bodily and plural form, drawing critical attention to the conditions of bodily survival, persistence and flourishing within the framework of radical democracy. If I am to lead a good life, it will be a life lived with others, a live that is no life without those others. I will not lose this I that I am; whoever I am will be transformed by my connections with others, since my dependency on another, and my dependability, are necessary in order to live and to live well. Our shared exposure to precarity is but one ground of our potential equality and our reciprocal obligations to produce together conditions of liveable life. In avowing the need we have for one another, we avow as well basic principles that inform the social, democratic conditions of what we might still call ‘the good life’. These are critical conditions of democratic life in the sense that they are part of an ongoing crisis, but also because they belong to a form of thinking and acting that responds to the urgencies of our time."

"Can one lead a good life in a bad life?" Judith Butler, Adorno Prize Lecture.

21st Century Sangoma

Dineo’s small arms are heavy with a multitude of red and white beads wound tightly around her wrists. Above them, ispandla made of goat’s hide. She pulls a Jenni Button jacket over her petite frame and heads to the Golf Gti parked in the basement of the Upper East Side Hotel. Onlookers, passer-bys and acquaintances who share the odd polite conversation would never know that she is a Sangoma.There’s a reddish-brown bible on her bookshelf. It props up a year’s worth ofGlamour and Elle magazines; and in the corner of her studio apartment, next to the sliding door that looks out onto the mountain, a sacred shrine on an ox-blood red mat with candles, imphepho (incense), and a spear. There is a perceived clash here. Her apartment holds all the accepted hallmarks of an upwardly mobile modern woman. The greys, the matt blacks and the shiny silvers of post-modernism juxtapose jarringly with the bright crimson spirituality.

She speaks of being a sangoma nonchalantly, absent of the usual over-gesturing and pantomiming that usually accompanies conversations of this nature. She’s more comfortable with her calling now; shedding the long sleeves, high necks and head scarves she wore to hide the chains, beads and shells that signified her reluctant mission. A calling conveyed to her through a series of recurring dreams. In one dream, Dineo would see herself speaking to a woman in an indeterminable language. The woman would respond in her mother-tongue, telling her she has to thwasa. Breezing through my barrage of ignorant questions, she pauses often to explain to me the duality of being a 21st century sangoma. To her, there is no clash, and becoming a sangoma required little adjustment. She attributes this to having a very tolerant dlozi (ancestor).

“Some people’s ancestors are very harsh and strict. They aren’t allowed to wear shoes, they have to look and dress a certain way. Some aren’t allowed to work or go to school. They have to devote themselves fully to healing others. For some, the dlozi must evidence itself physically. If your ancestor walked with a limp, you will begin to walk with a limp. Your voice will change. Your tastes and preferences are altered. One girl who was at training with me, would be left in excrutiating pain when her ancestors entered or left her body. So painful that she would faint. My life however, hasn’t changed much. Every morning and evening, I burn imphepho to cleanse my spirit and my surroundings. I’m not allowed to eat pork and certain parts of an animal, and I have to introduce my partner to my dlozi to bless the union. On the face of it though, I am still very much the same person.”

A beaded white chain hangs off her neck, where a rosary used to be.

Somewhere in the bible, someone warns against the worshipping of false-idols, a prophet warns against false messiahs; but somewhere else in the sacred, ancient texts a holy spirit is sent to live amongst man. A burning bush conveys a command. An angel visits a virgin and tells her she is carrying the child of God. Refiloe Lerumo, a 23 year old business woman and sangoma, claims her ancestors are angels. To her they are medium used by god to convey messages and healing. She is another link in the chain, bringing the ancestral and godly gifts to the masses.

It is difficult to not be cynical of something that superficially, seems so ethereal. Religion and spirituality are often viewed by today’s thinkers as child-like, unrefined solaces for people who lack the ability to deal with the everyday oddities of life. Science is the new God. Science makes sense.

Weekly, The Daily Sun “investigates” laughable tales of withcraft. “Man buys lightning bolt to kill ex-wife”. Monthly, chilling stories about muti murders and suspected witches being burnt or bludgeoned to death make their way to News24. Daily, A8 sized flyers are forced into my hand. Generally Powerpoint productions that fade from blue to a deep purple as they outline, in fractured English, a myriad of ills and spiritual ailments that Gogo so-and-so claims to be able to cure. “Do you have low sex man power? Do you need amagundwane (mice) for riches? Do want to run away court case? Do you want to reduce vagina?” Unfortunately, there is no quality control in the spirit world. No checks and balances exist to distinguish charlatans from bonafide Sangomas, and get-rich-quick scammers who prey on desperation and, sometimes, ignorance. How then do you verify cause and claim in a space where a headache is most likely going to be seen as curse or a spiritual ailment, rather than a physical one?

According to South Africalogue, over 200 000 Sangoma’s practice in South Africa, and over 80% of the population use their services. With consultations ranging anywhere from R50 to R5000, being a Sangoma is serious business. No real barriers to entry + no regulations + no ceiling on fees or medicine prices = opportunistic swindler’s wet dream.

Then there’s the more baleful side. Muti-murders and witchcraft. Potions that rob people of free-will. Suspected witches being bludgeoned and burnt to death. The genitalia of young girls are used to concoct fertility medicine. Wise men are decapitated, and their brains brewed to make potions for increased intelligence. Human blood is consumed to strengthen health, and extend life spans. This is the side that no-one wants to talk about. Veiled in secrecy, the community of traditional healers is happy to leave the sinister aspects to speculation. Refiloe confirms that the use of powers and trade of human body parts is real. “Some people use their gifts to cause to cause harm, but it always catches up with them eventually. The ancestors cannot be abused.” Still, the practise continues, and with no open dialogue, very little can be done to eradicate it.

The Traditional Healers Organisation aims to provide some legitimacy. They train and certify traditional healers, but their attempts to lend them any credibility is undermined by their own administrational failures. None of the sangomas I spoke to were registered with them, and all emails and phonecalls directed to the organisation went unanswered. Suffice to say then, their fancy website aside, they will not be the new age bridge between traditional healers and western civilisation.

Refiloe is what I’ve termed a Cyber Sangoma. On her website, she offers online readings and consultations. Another opportunity to be sceptical. She says reason behind the website is to provide clients with convenient access to her, but however noble its intentions are, one can’t help but sartorially picture her dumping her bag of bones and die onto the keypad of a Mac computer. Without physical contact, how is Refiloe able to connect to some else’s ancestors? Are the ancestors at peace with their gifts being used in this somewhat impersonal manner? Is my inability to grasp this just another indication of my ignorance, and complete lack understanding?

Where white is the colour of peace and tolerance, harsh shades of red are the colours of being a Sangoma. Forceful and unrepentant, it burns brazen with the colour of passion and heat, defiant of whether or not it is legitimised in an increasingly critical world. But there is a lot of grey scattered amongst the red. Questions that cannot be answered. Conversations that will not be held. The murkiness of the unknown, the unquantifiable. And while there is no method to prove the unproveable, the industry continues to grow, raking in millions of Rands a year. This faith-based contract is built on cultural legacy and funded by today’s money; but despite its popularity and profitability, it is still largely unrecognised by both the lawmakers and practitioners of modern medicine.

We’re reluctant to openly embrace it, and yet we’ve included alternative eastern practise as part of modern life. Yoga in the morning, acupuncture for healing; what is it about sangomas that discomforts us so? Is it because it represents a part of us that was meant to have died a long time ago? A backward notion held by the natives who refuse to be integrated into a globalised South Africa? Or is our reluctance to recognise it actually a fear? A phobia brought about our uneasy relationship with the great “unknown”. Do we need Madonna to do for it what she did for Kabbalah? Maybe get Mandoza to jump up and down on Noeleen’s couch before we pay it any heed? Perhaps what we need to be doing, is accepting Traditional Healers as a relevant part of South Africa, and not a relic of the dark days. Because one thing is certain, our denialiasm will not deter its prevalence

**This article was written by Lindokuhle Nkosi and initially published on Mahala. (http://www.mahala.co.za/)